skeletons (29 page)

“If I can do it, Annie Snackenberg, will you be my woman?”

She smiled again, extended her hand. I drew it to my lips.

“I will, B. James Butters,” she said.

I bit HER knuckle.

Waiting. A thousand of us on Gold Street, breath held, waiting.

A wind blew, a small incessant wind.

I looked at faces across the street, recognized one under titty-pink hair and behind eyeglasses with purple plastic frames shaped like butterflies. Miss Millicent Mills. Who, on the tenth of May, 1910, when she was a girl of fourteen, had hidden by the ticket window of the Crystal Theater, waiting.

Murmur.

HERE HE CAME.

Silence.

Suspense.

He was a tall handsome man with dark hair and mustache. He wore black serge vest and trousers, white shirt, a black string tie. In each hand was a .38-caliber Navy Colt with a six-inch barrel, high-gloss blue finish, oil- stained walnut grip. He walked at a moderate, purposeful pace, arms at sides, down the center of Gold Street toward us.

Walking thunder.

At a corner he was intercepted by a man with a sheriff’s star on his chest.

“Don’t do it, Buell.”

Loudly, so that all might hear.

The attorney did not pause.

“Leave them to me, Buell.”

“If you try to stop me, Blaise,” was the response, “I’ll kill you.”

Buell Wood proceeded.

Out of the Luna spilled Tigh Gooding and the Pennington boys, headed for their horses, were halted by the sight of husband and father. Bill Pennington took a reasonable step.

“Mr. Wood, we didn’t mean—”

The attorney stopped, raised his right arm, fired. Bill Pennington sank, pitched forward, lay still in shock, breathing hard.

His brother George and Tigh Gooding fled in terror down the sidewalk, took cover behind the Model T Runabout and the Coupe, drew Peacemakers, began firing wildly at Buell Wood.

He moved upon them.

“Goddammit, Wood!” Tigh Gooding yelled. “We’re sorry, goddammit! We’re sorry!”

He was shot in the left leg, howled, tried to hop from Runabout to Coupe, was shot again in the spine, collapsed, died instantly.

George Pennington lay on the sidewalk halfway under the Coupe. As he fired, a flare of flame enveloped his forearm. He screamed, dropped his pistol, stood upright.

“Oh I’m burnt! I can’t fight no more!” he screamed. “Mr. Wood I give up! Jesús Christ don’t shoot me!”

Buell Wood advanced to within ten feet, raised arm, fired. It was an execution.

Gold Street resonated with gunfire. The air around the Fords was clouded by the smoke of blanks.

Buell Wood looked left, where Bill Pennington lay groaning, arms hugging his belly.

The attorney went to him, lowered a revolver barrel to his temple, fired.

He pushed guns under his belt, strode then through the silence and the smoke across the street to the watering trough, stood for a moment over the body of his wife. Bending then, he lifted the doll which represented his daughter, Helene, cradled her in his arms, carried her through the pure spring afternoon away from death, away from us, down the center of Gold Street. He reached his office, opened the door, entered, closed the door behind him.

There was no applause.

But a sigh, almost sensual, was thrust from a thousand throats. Including mine.

It was true. I could never be the same. Even though it had been only a commercial come-on, a play within a play employing blanks and props and actors, the boy I had been a year ago could not have watched it. The man had.

I punched my Pulsar.

3:03.

I squinted down Silver Street at the clockface in the tower of Harding Courthouse.

3:03.

Men wait upon women. He waited on one side of the living room, I waited on the other. Both of us dressed to squire a dame to dinner.

“How’d you like it?” I asked, trying to get the conversational ball rolling.

“Like what?”

“The shootout.”

“It was okay.”

Insensitivity.

“Do you enjoy reading?”

“Sure.”

“Do you read a lot?”

“With my mom a librarian?”

Impertinence.

“Have you ever been to New York?”

“No.”

“Would you like to?”

“Not much.”

Disrespect. He was tall for ten, would one day be as long and lank as his father. James Stewart Jr. In no way would anyone ever mistake him for my natural procreative product.

“Do you mind if I call you something else instead of Ace?”

“What?”

“You don’t care for Jason.”

“No I don’t.”

“I know—how about Tex?”

“Why?”

“Well, because everybody in New York calls everybody from Texas Tex.”

“That’s dumb.”

“But is it okay if I call you Tex?”

“If you have to.”

Condescension. I could have kicked his uncooperative little ass. And he, I supposed, could have kicked mine. But I could understand the condescension. He’d had a hero for a father, a man who packed a pistol and roamed a dangerous range. I was a soft, sedentary sort. I pounded a typewriter. I never went anywhere or did anything dramatic. He wore a black jacket and white ducks and a white shirt and a bow tie and his sleeves were too short for his arms and his ducks too short for his legs. Wrists, ankles, and a cowlick at the back of his brown head. I would take him by the ear to Brooks Brothers as soon as possible. Provided I got the chance. And provided they’d permit him on their premises.

“Have you ever been across the border, Tex?”

“We went to Juarez once.”

“I’ve been down there just once myself. Acapulco. For a week. But listen, in the hotel dining room was a little pool, with gardenias floating, and in it lived a darling little turtle. The waiters called her ‘Chata,’ which means Pugnose. All Chata did all day was float around among the gardenias and eat goodies people fed her from their tables. And out behind the hotel lived a big fat pigeon the waiters called ‘Pedro.’ They baited a box trap for him every day, and watched to see if they could catch him and bake him in a pie. They almost did, too, by baiting the trap with cigar butts. Pedro loved cigar butts. Chata and Pedro were close friends. He’d flap through a dining room window at night and they’d have long heart-to-heart talks about life and things. She worried a lot, though. She often had indigestion from eating starches and sweets, and she knew it was only a matter of time before Pedro gave in to temptation and waddled into the trap and wound up in a pigeon pie. So she’d rest her pug nose on a gardenia and worry and sometimes shed a delicate tear.”

At least he’d listened.

“I always wanted to write a book about them.

Pugnose and Pedro.

I wanted them to save themselves, to go away together, but I could never figure out how they’d go, or where.”

Indifference. I felt a fool. He seemed to be thinking about something. I shot my cuffs and cursed Annie for being interminably tardy.

“I know.”

Surprise. He’d spoken without being spoken to.

“I know,” he said. “Pedro could fly and carry Chata on his back.”

I gaped at him. “On his back? Yes of course! But he’s so fat—how would he get off the ground?”

“She’d be the pilot. Like a pilot on a 747—they’d need a long runway to get up ground speed—they could take off from the beach. Then she’d fly him.”

“My God yes!” I said. “I can see the jacket—this fat pigeon flying at five thousand feet blowing smoke from a cigar butt and a darling turtle on his back holding on for dear life! Tex that’s terrific! But where would they go?”

We scowled at each other, racked our brains. Suddenly I clapped my hands. “Got it! They want a better life—so where do they fly to? Where?”

“Where?”

“The USA! They cross the border!”

“Sure!” Jason Snackenberg was on his feet. “Illegal aliens!”

“Terrific!” I cried. “Sensational!”

“Wait a second,” he said.

“What?”

“They can’t come to Texas.”

“Why not?”

“Border Patrol would pick them up on radar. Besides, all they could do here is pick fruit or work in the fields. That’s not much of a life.”

“You’re right.”

He began to awkward up and down the room, scowling. Now and then he’d make a funny, effortful face to show me how seriously he was into the collaborative process.

“Hey!” He clapped his hands. “I got it!”

“Say it!”

“California!”

“California? Yes! Los Angeles!”

“Hey, yeah!”

“The Big Orange!”

“Disneyland! They ride the rides!”

“Marineland! Chata talks to dolphins!”

“Hey I know!”

“What?”

“TV! Their own show!” “

‘Pugnose and Pedro’!”

“They’re rich!”

“They re starsl”

“Let’s go!”

“Let’s go!”

His mother smiled into the room. “Let’s go where? What are you two so excited about?”

“Hey, Mom guess what! Guess what Jimmie and I are gonna do?”

We grinned at each other like monkeys.

“Annie you won’t believe it!” I BUBBLED.

“Believe what?”

I BOUNCED out of my chair. “Tex and I are gonna write a book!”

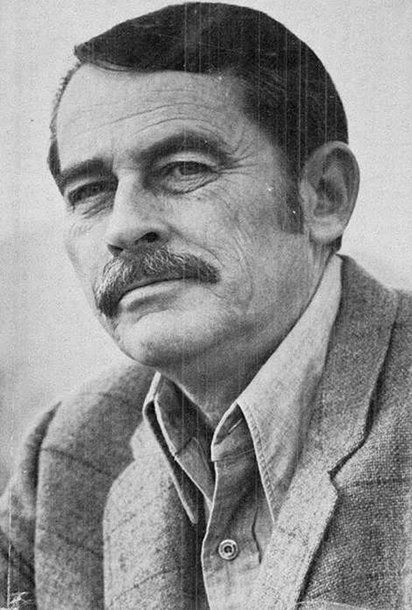

Glendon Swarthout

was the author of many novels, his most recent being

The Melodeon

. Two of his previous works

The Shootist

and

Bless the Beasts and Children

, have been made into films.

Table of Contents