Skylark (23 page)

Authors: Jenny Pattrick

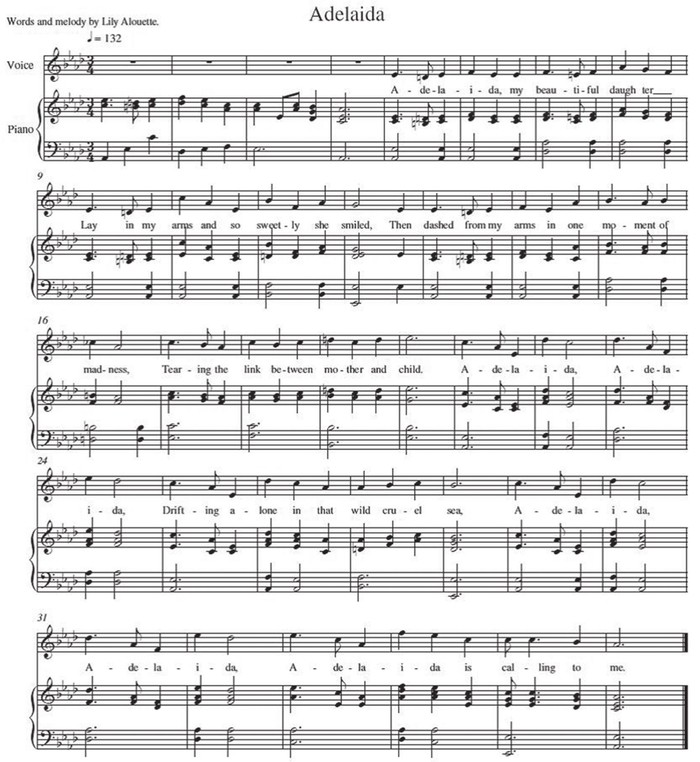

[Archivist’s Note: I am assured that the tune for Lily’s

‘Adelaida’

is not Beethoven’s song of the same title. Among some of the loose papers inside Mattie’s journal are some sketched tunes, in Lily’s hand. A musical family indeed! A musician friend has suggested that the two arrangements appended might fit the following songs. He has kindly transcribed them. E. de M.]

Adelaida, my beautiful daughter

Lay in my arms and so sweetly she smiled

Then dashed from my grasp in one moment of madness

Tearing the link between mother and child.

Chorus

Adelaida, Adelaida,

Drifting alone in that wild, cruel sea

Adelaida, Adelaida,

Adelaida is calling to me.

Hark, can you hear, o'er the far distant ocean

The cries of my baby â her pitiful plea,

âMother, dear Mother, my strength is fast failing;

Mother, dear Mother, oh where can you be?'

Wretched I swam but my arms could not find her

Fainting, half drowning, I still struggled on;

My sweetheart was sinking, dragged down by her clothing

Alas, little Adelaida was gone.

And though she is gone to her Father in Heaven

And though her sweet laughter no more will I hear

How oft I remember the pain of her passing

How oft feel her touch and believe she is near.

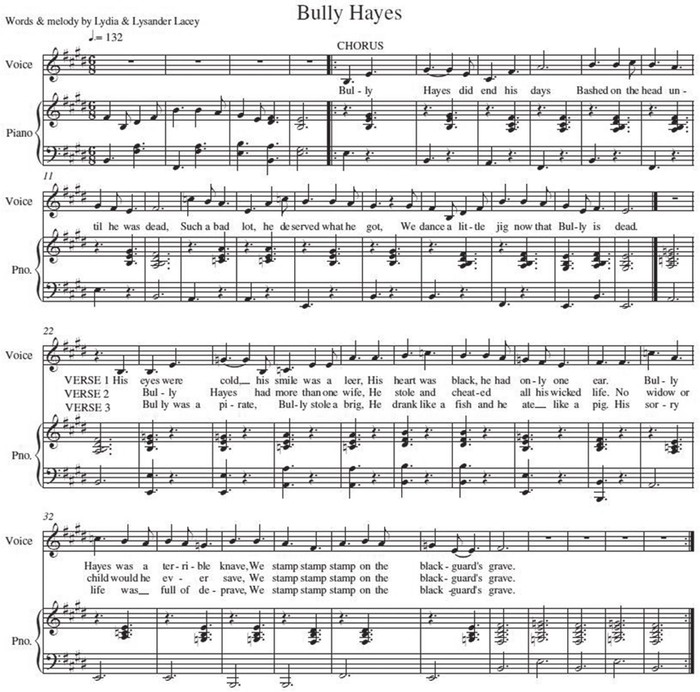

[Archivist's Note: Lydia and Lysander are introduced in the third journal. See page 238. E. de M.]

Chorus

Bully Hayes

Did end his days

Bashed on the head

Until he was dead

Such a bad lot, deserved what he got

We dance a little jig now that Bully is dead.

Verse One

His eyes were cold, his smile was a leer

His heart was black, he had only one ear.

Bully Hayes was a terrible knave

We stamp, stamp, stamp on the blackguard's grave.

Verse Two

Bully Hayes had more than one wife

He stole and cheated all his wicked life

No widow or child would he ever save

We stamp, stamp, stamp on the blackguard's grave.

Verse Three

Bully was a pirate, Bully stole a brig

He drank like a fish and he ate like a pig

His sorry life was full of deprave

We stamp, stamp, stamp on the blackguard's grave.

[Archivist’s Note: Mattie’s journal is more of a scrapbook than the other two. It contains many pages written in Mattie’s hand but also pages pasted in: letters, additional stories by Lily and Samuel, newspaper reviews and, surprisingly, one or two recipes. Interestingly, Jack Lacey never writes. Together the entries present a remarkable picture of the years 1864–83 in the life of this very unconventional family. You will observe that Mattie starts off her story as a sort of entertaining farce, as a complement to Lily’s melodrama, but cannot keep it up. Neither the material, nor her own character, are suited to a rollicking or bawdy style. E. de M.]

Oh what an uproar! Truly this might well be a farce as Lily had promised, but neither Samuel nor Lily will write another word. Accusations, tears, rages and towering silences are the order of the day between those two. Why, in the name of heaven, did Lily need to bring in this tale of her being with child when she left Bully? Now the rest of us are without our evening stories, which had been going so well. I have enough troubles without this.

Today Lily has saddled the grey mare and ridden off who knows where. I pray that she is not about to disappear again. Lily is difficult and sometimes arrogant, but she is the bright lamp that illuminates our peculiar household. I suppose I am the softer glow of the hearth fire that warms and feeds us. But we

are used to her liveliness and miss her dreadfully when she is suddenly gone. It’s no use thinking that those slips blocking the valley will stay her if she has a mind to leave. Lily on horseback can negotiate the roughest terrain.

But surely, at this time, she will not leave us. Surely?

Today Samuel came to me, his dear face haggard, his eyes dark pits. ‘What do you think, Mother Mattie, is she right? Can she be telling the truth?’

I paused in my kneading. Bread must be baked even when we are in an uproar. ‘Have you not asked your father?’ I said.

Samuel would have pounded the table were it not covered in flour. ‘Father is no help. He will take nothing seriously. He is so easy on Mother. He will never contradict her. “Well, that is Lily’s story,” says Father. “As far as I’m concerned, you are my son. I registered you, I named you, you were born and raised in this house.” But he will not answer the question of begetting. He simply smiles and gets on with his work.’

Samuel takes matters so seriously. He has always been Jack’s beloved eldest son. (We are surely not so scrupulous about

begetting

in this household!) And yet he has written down Jack’s story well: we have all enjoyed his readings, Jack especially. He sits there in front of the fire, grinning — sometimes laughing outright at the way Samuel has written down his life. And more than once I have caught him out on a tear, which he has dashed away with a flick and a shrug.

I suppose the problem is that Samuel has identified so strongly with his father. He loves Jack deeply, and now, if we are to believe Lily, Samuel may be the son of that villain Bully Hayes. Truly it was naughty of Lily to bring up the matter. Especially with the little ones listening.

I smiled at the poor, wracked lad. ‘Have you ever known your mother to embroider the truth?’

‘Yes, of course. Often.’

‘You don’t think that this might be one of those times?’

‘But why? Why would she? To what purpose at all? It does not heighten her story to make me a bastard.’

I plopped my loaves in their tins with more force than necessary. ‘Samuel. We do not use that word in this household, as you very well know. Leave name-calling to the neighbours.’

He quietened then. Looked at me sheepishly. He might well be considered a bastard by polite society without any intervention by Bully Hayes.

‘Now,’ I said, as firmly as I could, ‘I myself am going to continue the story, since you and Lily will not.’ Then I could not hold back my grin. ‘But this part of the story will not be for the younger children. Your mother was planning to write a farce, was she not? Well then, let it be a farce. Ha! Perhaps you, and Sarah, and Phoebe and Bert might be allowed to listen … We’ll see what your father thinks.’

That interested the boy. They have never heard about the early days, when Lily first came to the valley. But they should know. They might need to be armed against prejudice as they begin to leave the protection of this home. And we must get up to Teddy’s part. We must

all

listen to that story — Teddy and the Pollard Company. We must come to an understanding.

I am hoping that Lily and Samuel might be drawn into writing that part with me. Lily, at least, will not be able to help herself.

Ah, and here she comes riding back, flying over fences, her hair streaming and her cheeks pink. There is my Jack waving to her as she rides past the lower paddock.

Thank God.

A H

ORSEMAN,

T

HE

A

CTRESS AND

T

HE

W

ENCH AT THE

G

ATE

or

Who is the Wife?

NARRATED BY

Mrs Mathilda Lacey

AND

Others

Think back twenty years. Who is that pretty young girl standing at the gate? Why, it’s me: young Mattie Jones, daughter of a Welsh sailor (so the nuns said) and a native woman from Ranana up the Whanganui River. Perhaps I am of a chiefly family, perhaps a slave’s. I suppose I will never know: my mother and her family died in the early days when disease came to our settlement. I was brought up by the nuns. I am lucky to get a position with Mr Jack Lacey, who is kind and handsome. And he is lucky to get me! I am a good cook and housekeeper and strong. (And pretty, so the stable-boy and the groom say). The nuns thought I was clever and gave me an education in all the things they said I would need: sewing, cooking, cleaning and knowledge of the Bible. I also learned to read and write.

On this day I’m leaning on the gate by our house garden, dreaming. The very same gate you see today, covered in moss, with one hinge rusted almost away. To be honest, I’m dreaming of Mr Lacey who has been away for three weeks now. I have nothing much to do except dream: the house is clean for there is no one here to untidy it. The day, for once, is clear and windless. We’ve had a month of sulky weather where the mist lies heavy on the ground, lazily refusing to rise until midday. Every blade and leaf droops: my soul also.

Mr Jack Lacey has gone in search of a sweetheart. I know it. He does not talk to me of her, but I have seen it in the way he smiles sometimes: a yearning, sighing kind of smile that I am probably guilty of when I think of Mr Lacey. He is so handsome, especially

when on horseback. Some months back, there came a letter which gladdened his heart and caused him to run outside to the house paddock, saddle Alouette, gallop up the valley and then up a sheer slope until he was a tiny black silhouette, far, far above.

But now, as I lean and dream, here is another, quieter man on horseback, far, far

down

the valley. I shade my eyes; the sun is still low and I cannot see. But surely …? Yes! It’s Jack Lacey himself, returning. Not galloping up the last mile or two as is his habit, but plodding like any ordinary tired farmer. Slumped in his saddle. Oh dear, oh dear, this will not do. (Although I must admit to a small thrill of shameful pleasure: no accompanying sweetheart.)

I run into the kitchen, blow up the fire and set scones quickly to bake. No time for bread, the stale heel will have to do. But a good haunch of cold mutton hangs in the larder and there’s cheese and butter from the house cow. Here’s a meal for him. I’m singing as I work. ‘I Love the Merry Minstrel’ and so on. Mr Lacey is returning and our quiet life will have a centre again! My feet will not stay still; out I go again to pull some carrots and lettuce — but really to catch another glimpse.

There is the good man, riding up through the river paddock, taking something sweet from his pocket for the horses who trot to him like foals to a dam. Oh Jack Lacey would never forget his horses, no matter how down in the dumps he might be! Matiu over at the stables shouts and waves and Jack raises his hand in acknowledgement.

And has a smile for me too, standing at the gate. That gate is my waiting place: which one of you has not been greeted there by me? But oh, this day, what a crooked smile is Jack’s; how white his face; how drooping his shoulders! It’s as if he has brought his own personal shroud of ground-mist which hangs all about him and chills the bright air.

‘Hello, Mattie,’ he says, dismounting and handing the reins to Matiu who has come running. Matiu and I exchange a glance. Usually Mr Lacey will chat and laugh with us even after only a day or two away at Whanganui. Even though we are servants, he is never short with us. Some of the other farmers, who are

frightened to have native servants, with all the unrest about, do not know where to look or what to say when they ride over to see Mr Lacey and find us sitting at his table sharing a meal.

But today he might as well be one of those rude, uneducated farmers. Inside he stumps without a further word. I watch him from the little kitchen window as he takes water from the tank, splashes the dust from his face and hands, then flings the grey water out over the raspberry canes. All customary, familiar actions, but done so cheerlessly! I can no longer feel glad that he has come home alone. My Mr Lacey is heart sore, that is very clear.

He eats his mutton and scones mechanically, munch, munch, like Betsy, our dutiful house-cow, at her grass. I stand behind him, waiting to be invited to the table, but I might as well be part of the furniture. This will not do. He must not bottle up whatever the pain is or it will run through his veins like a poison. I fetch the decanter of brandy which is usually brought only out for important occasions, and pour him a good three inches.

He downs it in a gulp. I pour another, which follows just as quick. I decide to take a drop myself, just to keep the poor man company. After the third he looks up, reaches a hand to me as a drowning man might, and I can see the dam is about to burst.

I lean in to him, hold his head against my apron. There is no need to search for words of comfort, for his own come

flooding

out.

‘Oh Mattie, Mattie,’ he cries. ‘She has gone. Gone to Australia with another man’s child. What am I to do? I thought … I felt sure … Oh, I cannot bear it!’

Tears follow. I hold him gently, rocking him like a child, my own tears rolling down. What a mixture of feelings swirling within: pain that he should feel so bereft, but also a fierce joy to hold his dear body so close, and to know that he has need of me.

I dare to kiss the top of his head, where a damp, dark lock curls down to his forehead. He lifts his head, looking at me with surprised, swollen eyes. I kiss those eyes — how could I not? — and then his beautiful nose. Oh what a pleasure! I am lost now: a team of his very own horses could not stop me!

We climb the rough stairs together and — well, you can imagine what follows. Perhaps he dreams that another woman lies in his bed, not his maid-of-all-work. Perhaps you will blame me for taking advantage of a grieving man. But that precious night was full of healing and joy. Tears too, of course, but these became gentler as the night wore on.

By morning, Jack lay exhausted but at peace, ready to tackle the day’s chores.

I sang all day and cooked him a special meal: Kereru pie. That day I was inspired — the recipe an invention of my own.

Boil two good fat pigeons with an onion, a bunch of sage leaves, a tablespoon of malt vinegar and another of honey, a pinch of salt and an apple cut roughly. Cook for two or three hours.

Take the meat from the birds, saving the bones for soup.

In a pan melt a generous dollop of butter and then brown a good handful of flour in the butter. Add two cups of the strained juices from the cooked birds and stir until you have a rich gravy, then add the kereru meat.

Line a pie dish with pastry made with butter, egg yolk and white flour. Fill with the meat and gravy. Cover with more pastry, making sure to cut holes for the steam to escape.

Bake in the middle of the stove, with a good hot fire burning. A short time only is needed, so keep watch.

The flavour is best if the pie is left for a short time before eating.

Potatoes and watercress go well with this dish.

Note: The juices are especially delicious, so if you have some left from making the gravy, it may be supped as an invigorating broth.