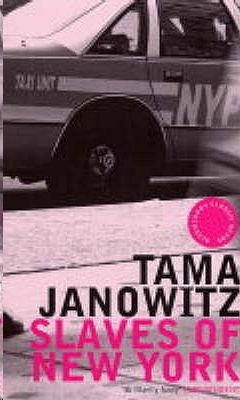

Slaves of New York

slaves

STORIES BY

tama janowitz

Copyright © 1986

ISBN 0-517-56107-7

This Book Is for

Phyllis, Lillian, Gwyneth, Anne, Julian, Joellen, Mary, Paige, Andy, Gael, Wendy, Caroline, Sam, Peter, Lizzie, Betty, Laura, David G., Ronnie, David J., Cynthia, Steve, Patrick, Agustin, Michael, Lulu and Beep-beep.

Modern Saint #271_____________________________ 1

The Slaves in New York_________________________ 7

Engagements__________________________________ 17

You and the Boss_______________________________ 36

Life in the Pre-Cambrian Era____________________ 42

Case History #4: Fred__________________________ 55

Sun Poisoning__________________________________ 58

Snowball______________________________________ 66

Who's on First?________________________________ 86

Turkey Talk___________________________________102

Physics_______________________________________119

Lunch Involuntary______________________________136

In and Out of the Cat Bag________________________140

Spells_________________________________________154

The New Acquaintances_________________________171

Fondue________________________________________185

On and Off the African Veldt_____________________199

Case History #15: Melinda______________________223

Patterns_______________________________________227

Ode to Heroine of the Future_____________________245

Matches_______________________________________260

Kurt and Natasha, a Relationship_________________273

But it wasn't a dream, it was a place. And you

—

and you

—

and you

—

and

you

were there. But you couldn't have been, could you? This was a real, truly live place. And I remember that some of it wasn't very nice

—

but most of it was beautiful.

Dorothy, in

The Wizard of Oz,

MGM Pictures

#271

After I became a prostitute, I had to deal with penises of every imaginable shape and size. Some large, others quite shriveled and pendulous of testicle. Some blue-veined and reeking of Stilton, some miserly. Some crabbed, enchanted, dusted with pearls like the great minarets of the Taj Mahal, jesting penises, ringed as the tail of a raccoon, fervent, crested, impossible to live with, marigold-scented. More and more I became grateful I didn't have to own one of these appendages.

Of course I had a pimp; he wasn't an ordinary sort of person but had been a double Ph.D. candidate in philosophy and American literature at the University of Massachusetts. When we first became friends he was driving a taxicab, but soon found this left him little time for his own work, which was to write.

When my job as script girl for a German-produced movie to be filmed in Venezuela fell through, it became obvious we were going to have to figure out a different way to make money fast. For a pimp and a prostitute, Bob and I had a very unusual relationship. As far as his role went, he could have cared less. But I didn't mind; I paid the bills, bought his ribbons, and then if I felt like handing over any extra money to him, it was up to me. At night I would come in for a rest and find him lying on the bed reading Kant, or Heidegger's "What Is a Thing?"

Often our discussions would be so lengthy and intense I would have to gently interrupt him to say that if I didn't get back out to work the evening would be over and I wouldn't have filled my self-imposed nightly quota.

I was like a social worker for lepers. My clients had a chunk of their body they wanted to give away; for a price I was there to receive it. Crimes, sins, nightmares, hunks of hair: it was surprising how many of them had something to dispose of. The more I charged, the easier it was for them to breathe freely once more.

As a child my favorite books had been about women who entered the convent. They were giving themselves up to a higher cause. But there are no convents for Jewish girls.

For myself, I had to choose the most difficult profession available to me; at night I often couldn't sleep, feeling myself adrift in a sea of seminal fluid. It was on these evenings that Bob and I took drugs. He would softly tie up my arm and inject me with a little heroin, or, if none was available, a little something else. For himself there was nothing he liked better, though he was careful not to shoot up too frequently.

Neither of us was a very good housekeeper. Months would go by, during which time the floor of our Avenue A walk-up would become littered with empty syringes, cartons of fried rice, douche bags, black lace brassieres, whips, garrotes, harnesses, bootlaces, busted snaps, Cracker Jacks, torn Kleenexes, and packages of half-eaten Ring Dings and nacho corn chips. The elements of our respective trades.

I was always surprised to realize how intelligent the cockroaches in our neighborhood were. Bob was reluctant to poison them or step on them. He would turn the light off and whip it back on again to demonstrate his point.

It's obvious they're running for their lives, he said. To kill something that wants to live so desperately is in direct contradiction to any kind of philosophy, religion, belief system that I hold. Long after the bomb falls and you and your good deeds

are gone, cockroaches will still be here, prowling the streets like armored cars.

Sometimes I wished Bob was more aggressive as a pimp. There were moments on the street when I felt frightened; there were a lot of terminal cases out there, and often I was in situations that could have become dangerous. Bob felt it was important that I accept anyone who wanted me.

From each according to his ability, to each according to his need.

Still, I could have used more help from him than I got.

But then Bob would arrive at the hospital, bringing me flowers and pastrami on rye and I realized that for me to change pimps and choose a more aggressive one, one who would be out there hustling for me and carrying a knife, would be to embrace a lifestyle that was genuinely alien to me, despite my middle-class upbringing.

When I was near Bob, with his long graceful hands, his silky mustache, his interesting theories of life and death, I felt that for the first time in my life I had arrived at a place where I was growing intellectually as well as emotionally. Bob was both sadist and masochist to me; for him I was madonna and whore. Life with him was never dull.

In any case, I liked having the things that money could buy. Originally I hailed from a wealthy suburb of Chattanooga, Tennessee, from one of the few Jewish families in the area. My great-grandfather had come from Lithuania at the turn of the century, peddling needles, threads, elixirs, yarmulkes, violin strings, and small condiments able to cure the incurable. All carried on a pack on his back; his burden was a heavy one, eight children raised in the Jewish persuasion. Two generations later my father owned the only Cadillac car dealership in town. I suppose part of my genetic makeup has given me this love of material objects. Or maybe it's just a phase I will outgrow as soon as I get everything I want. Even saints have human flaws; it is overcoming their own frailties that makes them greater than the sum of their parts.

I went to college at an exclusive women's seminary in Virginia. Until my big falling-out with Daddy, when I sent home F's for two successive semesters, and got expelled after being suspended twice, I had my own BMW and a Morgan mare, Chatty Cathy, boarded in the stables at school.

But I could never accept the role life had assigned to me; I fell in love with Jimmy Dee Williams, the fat boy who pumped gas at the 7-Eleven, and though the marriage only lasted six months, Daddy never felt the same about me. Well, he said, there are treatment programs for people like you. I didn't mind the time I spent in the institution. Fond recollections can be found in all walks of life. Yet if I had been allowed to go to a co-ed school I know things would have turned out differently for me.

Back in college the other girls would spend long evenings drinking beer and sitting on the rocking chairs that ringed the great plantation hall—the school had taken over many of the original buildings on a tobacco estate, and the new buildings were built in a Georgian style in a great semicircle facing the old mansion—gossiping about boys and worrying if they would pass French. But meanwhile I had to show them that I was wild and daring; I would pick Jimmy Dee up when he got off work and the two of us would smoke grass and drive around, bored and restless in the heat. One evening I drove right up onto the lawn and Jimmy Dee pulled down his pants to press his great buttocks, gleaming white, against the cool air-conditioned glass window of the car. That was the second time I was suspended from school; the first was when I had an affair with one of the black cafeteria workers in my dorm room, a man with only one arm who tasted of bacon and hair oil. . . . The only reason I was allowed to stay after that was that Daddy donated money to the school to build a new swimming pool. He never understood that no matter what he did, they were always going to think of him only as a rich Jew. . . .

I was finally asked to leave for good when Jimmy Dee and I were caught sneaking into the school pond, which was closed

for swimming after dark. Both stark naked, dripping with mud and algae. ... I tried to explain to Miss Ferguson, the dean, that I always got wild when there was a full moon, but, prim and proper in her mahogany office, smelling of verbena and more faintly of shit, she said she could see no future for a girl like me, that never in the course of all her years ... I had to laugh.

Before Daddy could find out about my marriage and divorce and take the car back from me (and have me locked up again? But there are no convents for Jewish girls), I had driven north to New York, sold the car for $2,000, found an apartment, and bought some new clothes. I landed a job in an internship program at a major advertising agency, even though I didn't have a college degree. . . . Once more Daddy spoke to me on the telephone; Mother and Mopsy even came up for a visit. . . .

I might never have found my vocation if I hadn't been evicted from my apartment, and after finding a new place in the East Village, met Bruno (ah, Bruno, that Aryan German, pinched, brittle in his leather trenchcoat, rigid as a crustacean —even a saint has her failures), who offered me the job of script girl on the film he was making in Venezuela, which in the end didn't work out at all.

But one thing leads to the next (doesn't it always?) and it was through Bruno I met Bob, and now at night, cruising the great long avenues of the city, dust and grit tossed feverishly in the massive canyons between the skyscrapers, it often occurs to me that I am no more and no less, a thought that I hadn't realized until my days as a prostitute began. (True, I have my bad days, when I cannot rise from bed, but who can claim he does not? Who?) I could have written a book about my experiences out on the street, but all my thoughts are handed over to Bob, who lies on the bed dreamily eating whatever I bring him—a hamburger from McDonald's, crab soufflé from a French restaurant in the theater district, a platter of rumaki with hot peanut sauce in an easy carry-out container from an Indonesian restaurant open until 1:00 a.m., plates of

macaroni tender and creamy as the sauce that oozes out from between the legs of my clientele.

As in the convent, life is not easy . . . crouched in dark alleys, giggling in hotel rooms or the back seat of limousines, I have to be a constant actress, on my guard and yet fitting into every situation. Always the wedge of moon above, reminding me of my destiny and holy water.

There was a joke that my cousin told my brother Roland when he was five years old. The joke went, "Fat and Fat Fat and Pinch Me were in a boat. Fat and Fat Fat fell out. Who was left?" And my brother said, "Pinch Me," and my cousin pinched him. So when my brother got home he told my mother he was going to tell her a joke, and he said, "Fat and Fat Fat were in a boat. Fat and Fat Fat fell out. Who was left?" My mother said, "Nobody." My brother repeated the joke, and when my mother said "Nobody" a second time, my brother kicked her.

Twenty years went by ... I was always older than my brother, and my mother still talks about my brother's fury at her incorrect response. All he wanted was to do to her what had been done to him. So now I'm living in New York, the city, and what it is, it's the apartment situation. I had a little apartment in an old brownstone on the Upper West Side, but it was too expensive, and there were absolutely no inexpensive apartments to be found. Besides, things weren't going all that smoothly for me. I mean, I wasn't exactly earning any money. I thought I'd just move to New York and sell my jewelry—I worked in rubber, shellacked sea horses, plastic James Bond-doll earrings—but it turned out a lot of other girls had already beaten me to it. So it was during this period that I gave up and told Stashua I was going home to live with my mother. Stash