Sleight (24 page)

Authors: Kirsten Kaschock

A PAIR OF SOLOS.

Dear Lark,

You think I can’t tell when you’re not there. Well, you aren’t quite the performer you think you are. I made love to you last night anyway, because I can’t not. I love you. This morning, when you left for the chambers with Clef, I decided it was time for Nene and me to go. This isn’t the right place for a four-year-old. And that’s what she is, Lark—a precocious four-year-old with an imaginary friend who happens to have your father’s name. That’s all. I know I sent you here with my blessings, but I’m taking them back. This thing, these people—they’re bankrupt somehow. I can’t explain it. None of you can tell me what it is you’re making, not what it means, not why it matters … and yet, you can’t think or talk about anything else. I didn’t tell you last night, but I brought up your jars. I’m leaving them with West. After Nene’s birth your painting—your Souls—they seemed to help you come back to me. To us. Come back to us, Lark. Please.

Love, Drew

Drew folded the note, sealed it, left the envelope on the kitchen table. West showed them out. He gave Nene a kiss on the forehead, a candy cane for the road. He patted Drew on the back, said Clef would be relieving Lark soon, this week or next, he’d send her home. He went back into the house. In a cardboard box in the foyer, a foot below the rail of the wainscot T had helped him to restore, were the baby-jarred colors of Needs. West walked through the living room, scanned it for remnants of the party he hadn’t gotten the night before. He picked up a burgundy throw from behind the couch, took two stone mugs off of the mantle, and moved toward the kitchen. He rinsed the mugs, set them in the sink, plucked the envelope from the table, opened it, and read. Then he walked over to the pantry, pushed open the door that didn’t latch, stepped on the lever that opened the small silver trash can just inside, and dropped in the letter. West reached up to a high shelf for the granola—a stretch: like most Victorians, his had tall ceilings. He went to the refrigerator for soy milk, the dishwasher for a clean spoon. He sat down at the table and ate breakfast. He wasn’t happy. In the bustling party preparations, he’d forgotten to buy himself dried blueberries.

FIRST DUET.

L

ark was teaching Clef. Lark showed her sister, explaining with her hands, the nuances of manipulating these architectures. Clef was amazed at her own navigation. She had wanted to curtail it, to work against West, but it wouldn’t be stopped. She had looked at Lark’s drawings and seen through her own body. She had seen inception. This sleight was in her. Maybe actually inside of her, next to the fetus, antifetal. On the very first day of the navigation, her notion of the child became entwined with the work. She could no more limit the sleight than she could control the growth inside her. She thought about the sleight very hard. And every time she thought

sleight,

she meant

fetus.

Or

tumor.

When she concentrated on the navigation hard enough, she felt everything in her dividing. In no time at all, every cell was multi-cellular—infinite. She was mother, artist. Connected by the same thread of worry, the same desire—what might she pass on.

Some nights, after rehearsal, she thought she could sense differentiation. Soon the sleight would have a beginning, a middle, an end: she just hoped, in that order. Because of West’s involvement, because of her mother, because of Lark’s Needs, there was nothing Clef feared more than the monstrous. The unbounded. It was why she worked at the navigation with love. To forestall deformation. But what was unconditional—mightn’t that be monstrous too? Every way open to her was fouled by a possible future.

After three hours in the cold chamber, Clef was beyond sore; she was shaking. Lark went to her.

“We should stop.”

“Why?” Clef doubled over, hands on knees, catching breath. She stood up. “I can do this. It’s mine to do.”

“It is.” But Lark didn’t move to continue instruction. Since Clef had started navigating, neither sister had discussed West with the other. It helped that he had absented himself from the process. They both knew that would only last as long as the sleight being produced was the sleight he wanted.

“But?” Clef’s voice was filled with air. She was still working for oxygen, her chest heaving.

“You’re pregnant.”

“Really? And you know what about motherhood exactly?” Clef flinched after she said it. She didn’t know when she’d developed this streak, this talent for letting fly words that stung in both directions. She bent a leg beneath her, folded her body into the floor.

“I love Nene.” Lark looked down at Clef before joining her, cross-legged in the middle of the chamber. They were a two-person séance. A Ouiji.

“If you love Nene, you should be with her.” This time Clef meant to convince.

“Now,

now

that you’ve decided you can be a mother, you’re going to tell me how to do it?”

“Only how not to.”

They were both still. The room was still. Nothing knocking about the walls, or under the floor. No ghost, no message. Clef spoke again.

“Do you think … did Jillian love us?”

Lark thought. This is where an answer should provide itself, letter by letter. She looked around. A floor, walls, a door, a window, mirrors. And above the mirrors, the wall of this chamber, like all of York’s chambers, had been stenciled with numbers, not the alphabet. The sleightists in Kepler laughed about it. West and his primes—one of the essential organizations of the original things. Hands often used primes to sequence their structures, but to Lark, math seemed as arbitrary as anything else. Someone had invented math too, as someone had once invented science, language, and before that God. Someone was always trying to pin things down, to corset them. What could be more breath-stealing than omniscience?

“I know she did.”

SECOND DUET.

In the car.

“Daddy?”

“Yes, Nene.”

“Sometimes I get mad at Mommy.”

“Me too.”

“But Daddy.”

“What, Nene?”

“Mommy can’t help it.”

“Can’t help what?”

“She wants this. She’s hardly ever wanted anything. And it’s Christmas.”

“It was Christmas yesterday.”

“Then it’s almost New Year’s.”

“Meaning what exactly, Nene?”

“The year turns over.”

“Turns over?”

“Yes. Newt showed me. Nothing keeps counting. Everything’s at o, o-o-o, like a string of baby robins’ mouths.”

THIRD DUET.

B

yrne had taken back the precursor and stared at it for days. It was New Year’s Eve. White outside. Marvel was due back soon, maybe. West had gotten him new paints from somewhere, and they were working. Marvel was in whatever constituted paradise for Marvel. He returned to Byrne’s apartment to eat and sleep and talk endlessly of hue and saturation and depth of field and integument and other things Byrne didn’t understand and didn’t care to. Byrne nodded. Byrne didn’t leave the apartment. He didn’t want to see Lark, he didn’t want to hear about her, didn’t want to think of her leaving, didn’t want her to stay. Nothing was coming to Byrne. Marvel said that Clef and the rest of the sleightists were dogs. They’d had three days off at Christmas, although few had left to see family. In consideration of that short break, they’d agreed to work through New Year’s. Marvel said they’d been there ten hours a day. “Dogs,” he said. “Bitches.”

“Marvel, why don’t you shut the fuck up.”

Marvel, just in the door, was shaking off huge flakes like dandruff. He smiled. “A little touchy, Byrne, with the block?”

“You have no memory? You’re completely devoid?” Byrne was looking at his brother. His eyes were metal. He stood from the table and walked toward Marvel, rock in hand.

“Ah. Date, date. Who’s got a date? Do you have a date tonight, brother?”

Byrne stopped. “So you haven’t …”

“Forgotten? What, the day I killed your father?”

“Our father.”

“Who aren’t in heaven. Wasn’t much of a father until he was dead, if you ask me, Byrne. Since then, of course, he’s kept you in line.” Marvel had removed his army jacket and dropped it onto the floor. “Can we have some hot chocolate, you think?”

“You want hot chocolate.”

“I want to sit down and get warm. And you’ll want to switch hands.”

“What?”

“I’ve seen you now and again, Byrne—I’ve noticed the change. I figured a sensitive soul such as yourself would make it into a ritual. What happens when you do it? Do you get shaggy, howl at the moon? Eat women? I would.”

“I forget.”

“Of course, you forget.”

The two brothers sat across the card table from one another. One had his hands wrapped tightly around a cup. The other sat with both palms flat on the table in front of him, the piece of granite between them. His head was lowered. The words he spoke were impenetrable to Marvel. “What are you saying?” Byrne continued. Marvel waited, though he didn’t like to wait for anything. When Byrne finished, Marvel asked again.

“What were you saying?”

Byrne looked at his brother. “I made Mom teach me.”

“What?” Marvel was getting agitated.

“She said it every day for eleven months,” Byrne explained. “Though I was supposed to. I caught her saying it at Thanksgiving and made her teach me.”

“What?” his brother was gritting his teeth.

“The kaddish.”

Marvel’s eyes lit up then, and he nodded to himself. “So, you

don’t

know what you’re saying.”

Byrne looked back down at the rock. “Not really … She loved him, you know.”

“I did know.” Marvel blew into his cocoa.

Byrne’s hand twitched. “They wouldn’t let her come back home after he died.”

Marvel sipped, swallowed. “No, why would they?”

Byrne’s hand twitched again. This time it seized the rock.

In Cape Town it was summer. From the plane, they could see the different way the light hit the earth. Because of summer. They went straight to the hotel when they landed, a hotel connected to a mall. Haley asked the driver of their bus to interpret a familiar-looking sign along the roadway. The man’s smile was sad as he slowed the bus to turn almost completely around in his seat. “It says, ‘This Land You Live on Is a Cursed Land.’ Or maybe more like a land of horror—I’ve heard you have these in America, yes?” He went back to the road. When they arrived at the hotel, he told them to stay close to the complex. “I’m worried for your group,” he said, “all so new.” Marvel and West, after checking in, headed straight to the hotel bar. Byrne went to bed, having not flown well. Most of the other sleightists talked and decided to stay up that afternoon, outwake the lag. They didn’t have to be in the theater for two days.

While heading to their rooms to drop off luggage, they passed through a long hallway. Elaborately matted political and festival posters were mounted close together in beautifully crafted, porous wooden frames; the even spacing, equal frame size, and quick striding of guests down the hall made the series an almost entirely subliminal film. But Latisha, at the back of the group, stopped in front of one with block print and an image of a young black man carrying a limp boy, and set her immense suitcase against the wall. T stopped a little ahead, waiting for her.

“Junie—that’s June. The sixteenth. This is my birthday.”

“How did I forget you were a Gemini?”

“It’s Bloomsday.”

“What’s that?”

“The day

Ulysses

takes place. June 16, 1904. Dublin.” “Ulysses?”

“James Joyce’s

Ulysses?

Best novel written in the English language in the twentieth century—that

Ulysses?”

“Never read it.”

“Yeah? Well, me neither. Tried to once—my birthday and all.”

“But that’s what this poster’s about?”

“Nope. This is that boy, Hector. Or was it Henry? It’s for National Youth Day.”

“What’s that?”

“The uprisings in Soweto? The beginnings of the end of apartheid?”

“When was that?”

“Happened on my birthday, apparently.”

“Yeah, Tisha. You just said. I mean, the year.”

“You know, I have no idea.”

Marvel shook Byrne.

“Get up. I want to go to the botanical gardens.” Marvel was already dressed. Or maybe he hadn’t undressed.

“What?”

“Get up. You’ve been passed out on top of that comforter for fourteen hours. With your shoes on. Take a goddamn shower and let’s get moving.”

“We’re going to see flowers?”

“Don’t get smart, puke-boy.”

Half of the sleightists had decided to take a ferry to Robben Island, where Nelson Mandela had been imprisoned for a quarter century, and before him lepers, the chronically ill, the insane. Their driver had suggested the tour; his brother-in-law had been incarcerated and now lived and worked there. “The place,” he said, “is deeply affecting— there are postcards.” The others, less inclined to the self-education available to day tourists, went to walk down by the waterfront, which housed theaters, restaurants, and a shopping district—a familiarly upscale development project that neither demanded nor promised. Marvel and Byrne went alone to the botanical gardens on the eastern slopes of Table Mountain, the large outcropping that defined the side of the city not oriented to water.

The colors at Kirstenbosch were of a quality Byrne couldn’t readily identify. They were both vivid and hushed. Byrne felt as if he were looking through a tinted lens, but he wasn’t sure what part of the spectrum he was being denied. The colors were compressing something inside his chest, something like a sob, or maybe it was just the traveling—he still wasn’t used to it. But no, another pang. It was Marvel doing this, on purpose, with the color. Some awful kind of sharing.

The gardens weren’t crowded. Most of the guests were European tourists, with impressive cameras and chic leather bags. Byrne had left his camera in York, having of late lost his taste for documentation. An Asian family in summer hats was frescoed beneath the pom-pom tree advertised on the front of the brochure they’d been handed at the entrance. It was no longer in full bloom. An older woman strolled ahead of them, humming to herself and, as if in love, stroking with the back of her hand her own downy cheek. She could’ve been local. A thin black man in his twenties was sketching on one of the benches—art student? Marvel kept his head down, touching plants. Byrne stopped guessing at the people and started reading names from off the little placards, names of flowers he’d never heard before—

Agapanthus

and

Vygies

and

Bloodflowers

—but Marvel didn’t want them said aloud.

“You can’t hear color, Byrne. Sometimes you can feel it, but you can’t hear it, especially not in Latin.”

“It’s not all Latin. And I can hear color.”

“I’m sorry, what are you babbling about?”

“All words have color. Your name, for example. What color do you think your name is?”

“My name has no color. Don’t you think I’d know it if my name had color?”

“Like you knew you were Jewish?”

“I did.”

“Bullshit. Your name, Marvel, happens to be persimmon.”

“What the fuck?”

“The color of persimmons, the fruit.”

“I know the color. My name isn’t ‘persimmon.’ What a fucking pussy-ass word.”

They walked through the gardens for another hour without talking. Marvel kept holding leaves and petals against his palm, checking them, Byrne supposed, against his flesh tone. Byrne knew he should be intrigued by the feathery grasses, that he should be admiring the slenderness of lilies and the glittering of foreign insects that weren’t foreign here. But this life didn’t interest him—it was what it was. There was no art in it.

Byrne had never been, not ever, in a place that wanted him. Marvel had done his own chores and then his older brother’s so Byrne would go with him to the quarry on the weekends, but the pit was too white and too wide. It didn’t like them there. The earth couldn’t recover from such a gash, and Byrne knew it was wrong to play inside a wound. Undaunted, Marvel started riding up there alone at eleven, and eventually ended up in a pack of delinquents who hung out between the woods and the gaping. Byrne spent most of his adolescence reading in his room, enwombed, though the house hadn’t wanted him either. And then, when he’d finally left, it got to be a grave.

With duct tape, he’d tacked up pages X-actoed from library books on the cinderblock walls of his dorm room in a gesture of grief or ownership. It was the beginning of a lesson: words, like places, were not to be his. Not ready to use his father’s death as a pickup line, he’d said little about it after he’d gotten back to school, but carried the rock. He became an icon of stoicism in only his second semester on campus. But by early April he’d softened a little, and one night asked his roommate to find another place to sleep. He brought up a girl he’d been watching since he’d come back—violet lipstick and fishnets in his Milton class. Amelia, like the pilot. After they were done with the awkward sex—his first time with a rock—he told her about Gil in a secondary gush he thought was emotion. She’d listened, then complained about the wordy décor, that his taste in poetry was leaden. “Ezra Pound? You think being a man is hard?” She was laughing. She didn’t tell him what was harder, but Byrne knew. He had no right to what he couldn’t feel. He left his walls alone after Amelia. And started jotting down language, his own, which laid claim to nothing.

Byrne didn’t want to examine plants. Things directly hurt. Thorns, the smell of chlorine, yellow. He kept looking instead at the muted sky, which seemed to have a warmth to its blue, as if it were reflecting the oceans that converged there, just below them, below the tip of the continent. When he called Marvel’s attention to the strangeness of this one, this sky, Marvel asked him what color he thought Lark’s name was. “Brown,” Byrne said without hesitation. “A dull gray-brown, like you’d expect.”

When they got back to the hotel, West was sitting on a leather ottoman in the lobby, reading a German newspaper. He looked up when the brothers entered, then folded the paper and stood to greet them. He was in formal mode and Italian shoes; Byrne had seen neither since their European tour.

“Did you find what you were looking for?” The question was directed at Byrne, though Byrne wasn’t aware he’d been looking for anything.

“You mean, did Marvel?”

“No,” said West. “I meant you. Did you find the rest of the words?”

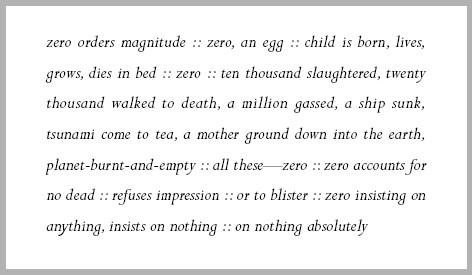

West was still dissatisfied with the precursor. Byrne had spent the first week of the new year reworking it. But it wasn’t brutal enough, and West refused to name the sleight. It was listed on the playbills of the tour as

[untitled],

lowercase

u.

Byrne was supposed to perform the words again on this tour, from up in the ropes, but the idea made him uneasy—nauseous, if he thought about it too much. He’d suggested West record the words. Since Byrne met him, West had been saying they needed to integrate more technology into the art form—why not sound? The precursor, though, West insisted, had to be reactive. This was absurd, of course; most troupes had the precursor read onstage before the curtains even opened. West was torturing him. And to be painted black by his brother? It already felt like being dipped in oil. Marvel’s hand in the process would only darken it, make a seal, night him.