Small Man in a Book (3 page)

Read Small Man in a Book Online

Authors: Rob Brydon

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

On Sunday afternoons we would go for a run in the car, perhaps east to the seaside at Ogmore or west to Oxwich. When it came to holidays we travelled to spots in Britain and beyond into Europe, where on a trip to Italy I caught mumps and the hotel owner encouraged us to leave earlier than planned. Closer to home we stayed at Mullion Cove in Cornwall with Uncle Colin, Aunty Dilys and my cousin Kim, all travelling down in Grandpa’s metallic-blue Mark IX Jaguar. Once at the hotel Dad became known to the other guests, most of whom were English, as Jones the Jag. Fittingly enough, for a child who would go on to find a career in comedy, we once stayed at the Gleneagles Hotel in Torquay, famously the inspiration for

Fawlty Towers

. My parents remember being in the bar one night at around ten o’clock, enjoying a drink with the other guests, when the owner suddenly pulled down the grille, switched out all the lights and went to bed, leaving his guests in the dark. Perhaps someone had mentioned the war.

Nan and Grandpa would often take me to stay with Aunty Ann and Uncle Peter, who lived now in England. My first ever memory of London is of being driven by Uncle Peter along the Embankment and having Cleopatra’s Needle pointed out to me. I wasn’t especially impressed.

I was a happy little boy, sociable, stoical and keen to entertain, whether it was at home, popping out from behind the long wine-coloured curtains in the living room, or at the little preschool nursery I attended at the age of three, run by Mrs Salvage. I had a group of friends here; we would dress up in a variety of outfits and I would entertain them with songs and jokes. Dressing up was a big part of my life in those early days. Each Christmas I would receive a new outfit and wear it that afternoon when we visited my Aunty Margaret, Uncle Tom and my cousin Jayne who lived further up the hill in Baglan. I would knock on the door, then hide out of sight until Uncle Tom came and expressed shock at the vacant doorstep. This was my cue to leap into view and blast him with my ray gun or pistol (depending on whether I was a spaceman or cowboy), at which point he would feign injury – or sometimes, if I’d been a particularly good shot, death.

My Napolean complex often led to sudden outbursts of anti-social behaviour.

Mum and Dad made those early Christmases truly magical. The excitement at the prospect of a visit from Father Christmas was almost as difficult to bear then as it is to comprehend now. The house would fill with satsumas, nuts and tinsel; lights of red, green, gold and blue would be hung on the tree. Like the shopkeeper in

Mr Benn

, my presents would always appear, as if by magic, at the foot of my bed. I can still remember waking in the early hours and glimpsing their shadowy outline in the darkness, pillowcases stuffed full of surprises and delights. One year I received a Dansette record player in red with a cream-coloured lid and sat cross-legged on my bedroom floor at five o’clock in the morning, playing a Rupert Bear record again and again, marvelling at the sound coming out of the little mono speaker hidden away in the housing of the machine.

Throughout my childhood I always had all the toys of the moment: Spirograph, Flight Deck, Ker-Plunk, Cluedo, Mastermind, Mouse Trap, Operation, The K-Tel Record Selector. They all came into the house in pristine condition and then left piece by piece, slowly and mysteriously, over the coming years, like British soldiers slipping quietly out of Colditz – oddly enough, the one game I didn’t own.

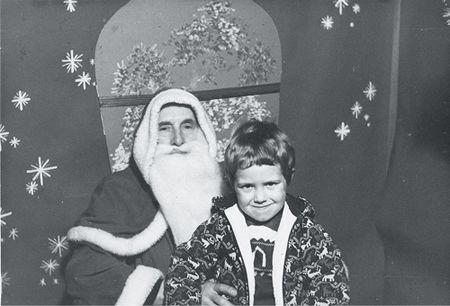

I place my mind elsewhere as Santa reaches his own conclusion.

I’d be happier if I could see his other hand.

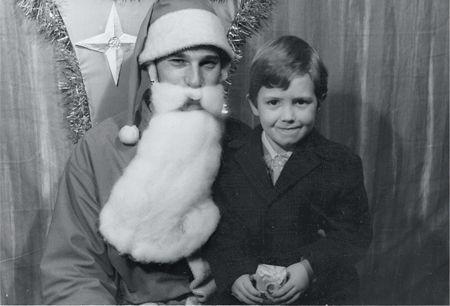

Please do what he says or he will kill me.

Finally, a Santa I can trust.

2

By 1970, just after my fifth birthday, it was time to start school proper. I went to a private school in the nearby coastal town of Porthcawl. St John’s, an idyllic-looking prep school for boys, was set at the end of a tree-lined driveway and had as its motto

Virtus, Sapientia, Humilitas

(Virtue, Wisdom, Humility). As luck would have it, very much my own watchwords at the time.

My first day at St John’s was a rather traumatic one. I cried bitterly as my mother tried to extricate herself from my soggy clutches. As she struggled to leave, another boy came over and, straight from the pages of a novel, said, ‘Don’t worry, ma’am, I’ll look after your little boy.’ Such kindness. The school, though in Newton, Porthcawl (on the South Wales coast), is forever frozen in my memory as a minor English public school; it seemed very precise and just so. Dad remembers hearing a teacher once shouting at a pupil from some distance, ‘

Wackerbath! Get orf the grass!

’

They were very strict about uniform, not just with the pupils but also with the parents. I don’t mean that fathers had to drop off their sons wearing shorts and a cap, but that the school was especially particular with regard to where the uniform had been purchased. We duly set off for the prescribed outfitter, Evan Roberts on Queen Street in Cardiff, a rather imposing store, from which every item on the long list of garments had to be bought – even the grey V-neck jumpers, which would surely have looked no different if they’d been picked up for a fraction of the price at the Port Talbot Peacock’s. I was kitted out with all the necessary uniform and equipment. Unfeasibly long shorts and socks, along with a still stiff new shirt for rugby (a game that terrified me), all contained in a soft brown cloth drawstring bag. We wore shorts in the summer as part of our uniform along with a blazer and cap. Everything was new, not a hand-me-down in sight, one of the advantages of being the first child. I had a brand-new leather satchel for my first day, a wonderful, robust and shiny vessel that smelled of leather in a way that nothing has smelled of leather before or since. This glorious smell has stayed with me all these years and now, on receiving a gift of a leather diary or perhaps a wallet, I’ll immediately plunge my nose in and stay there for a minute or so. I’m back at St John’s and everything is new and unknown; it’s all to play for.

It was very much an old-fashioned school inasmuch as competitive sports were encouraged and the food was appalling. Beetroot appeared on the menu with frightening regularity, as did rice pudding, both dishes way too exotic for my limited palate. The competitive sports took place mainly on a large field to the left of the driveway as you approached the school, or on the dreaded rugby pitch over on the other side. I have a collection of Polaroid photographs taken on a bright summer’s Sports Day; in one of them I’m competing in the sack race and still hopping along in my hessian prison while the rest of the course is clear, the other boys all having finished the race, completed the random drugs test and set about preparing themselves mentally for the next event. People often ask if my work is autobiographical, and I’ll typically say no, cleverly throwing them off the scent. In fact, this photo appears in the first episode of

Human Remains

as an example of my character Peter’s ineptitude at sport.

It could just as easily be me.

I remember very little of the actual lessons at St John’s – in fact, try as I might, I can only conjure up two classroom-based memories from my whole time there. The school taught maths in a very peculiar way involving small coloured pieces of wood, each colour corresponding to a particular length of wood and representing a number. There is a name for this method but it escapes me, as did the ability to gain even the most basic understanding of its workings. I remember the colours, though, and the feel of the little wooden sticks, which I would use to build tiny houses while the teacher had turned to face the blackboard. It is in this classroom that my other, far more specific memory is found. It is a sunny day (I have no memories of St John’s where the sky is not clear blue and the sun is not shining), the teacher is talking, it’s maths again and my mind is wandering out through the window and up into the trees from where I can survey the fields and the roofs of the buildings. I have a compass in my hand, the sort used for drawing circles rather than for finding true north. I’m attempting, unsuccessfully, to harpoon the top of the pencil with the point of the compass. Try as I might, it won’t go in. And so I give it one last big push, and in it goes – into my thumb. I look down and see the instrument buried deep in the fleshy pad of my fattest digit and want to say something, ‘

Ouch!

’ ideally, but know that this would attract attention. So, instead, I calmly remove the compass, wrap my thumb in my handkerchief and carry on as if nothing had happened.

And that’s about it as far as memories of St John’s go.

After a couple of years at St John’s I switched schools. Following a bout of measles when I was three I had by now paid a couple of visits to hospital for operations on my ears, and my hearing was far from perfect. Mum was concerned that this was holding me back in class; I was struggling in maths, especially. She remembers the school not being entirely sympathetic or willing to hold my poor hearing solely responsible for my academic shortcomings. They may have had a point. This, and the fact that the promised introduction of a minibus service from Port Talbot to Porthcawl never materialized, was enough to prompt a change. I headed west to Swansea and Dumbarton House School, another private establishment, though this time co-ed.