Small Man in a Book (32 page)

Read Small Man in a Book Online

Authors: Rob Brydon

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

At one point, I did get close to getting a proper, established agent. I’m not sure, but I think it was the actor and impressionist Alistair McGowan who gave me an introduction to Vivienne Clore. I duly went to meet her at her offices in the West End, where we got on like a house on fire and she said that she’d be happy to represent me. This was based solely on hearing the many voices I performed on my voice reel; she’d never seen any of my acting tape, but flattered me hugely with regard to my voices, telling me that I reminded her of Peter Sellers. If you ever want to get to the heart of a voice-over artist, tell them that they remind you of Sellers; they’ll be putty in your hands.

I knew that she wanted me primarily for my voices and the money that they would bring in; the problem was that I was perfectly happy with my voice agent at the time and was only looking for acting representation. I didn’t want to risk upsetting my current voice agent by leaving, but at the same time really was quite desperate for a proper acting agent. I was concerned also that Vivienne had never seen me act, although she assured me that she had heard that I was very good. I said I’d be happier if she’d take a look at my acting reel, just so we’d both be singing from the same hymn sheet, as it were. I left the office, promising to send my acting tape as soon as I got home and secretly thinking that maybe I

would

leave my voice-over agent if it meant being represented by Vivienne.

As soon as I got home, I packed one of my trusty VHS cassettes into a padded envelope and trotted off to the Post Office. I assumed that I would hear from Vivienne within the next couple of days, we’d hit it off so well.

A silent week went by, then another. I heard nothing.

I tried phoning but always managed to call when she was very busy indeed or had just that minute popped out of the office. Eventually, using one of the voices that she so admired, I rang in the guise of someone else – I forget who – and got put straight through. On revealing my true identity, there followed an awkward pause and then an even more awkward conversation in which she repeated her praise for my many voices (I think the godlike Peter Sellers reared his head once again, though this time in a more placatory role).

Then came the killer line.

I was calling from the phone box inside the main entrance to Kew Gardens. Martina and I had gone there for a walk – she was standing a few feet away, waiting for good news – and I had Katie in a sling on my chest, fast asleep.

I listened as Vivienne continued.

‘I love your voices, Rob. I really do … and I would represent you for that in a flash, you know I would. It’s just that your acting … well, it’s … It just doesn’t do it for me, I’m afraid.’

It’s quite unusual that someone is this honest when issuing their rejection; it’s rarely person to person, usually done by letter, and fudged under a fog of multifarious reasons (none of which could ever be construed to imply any shortcomings on the part of the aspiring actor). I have two separate rejection letters from my current and, I hope, final agent, the splendid Maureen Vincent, dated February 1990 and September 1993, both times explaining that it was the fact that she wasn’t in a position to take on any new clients that prevented her from offering me representation.

The artiste, when faced with this kind of stock letter, valiantly convinces himself that the agent is actually desperate to take him on and is now kicking herself in the depths of her plush London office, furious for having taken on so many clients. Yesterday she’d had to turn away Al Pacino, today Rob Brydon. If only she hadn’t taken on so many clients in the first place!

We walked away from Kew Gardens under a little grey cloud of defeat and rejection, yet again.

Ho hum.

If there was a good side to the lack of acting work, it was that being busy with voice-overs allowed me to spend lots of time at home and meant I was able to take Katie to her various preschool activities. I was a regular at Tumble Tots, walking alongside her as she clambered over huge squashy platforms, and encouraging her to take chances and climb ever higher. I’d always liked being with the children Martina had looked after while she was working as a nanny, and now that I had my own child my happiness reached a new level.

Yet I was beginning to wonder if it would ever happen for me. I suppose I was becoming resigned to a life of voices and the odd tiny role on the television; I suspect that I was inwardly preparing myself to admit defeat.

How was I to know that I just needed to hang on a little bit longer, just make one more push …?

PART THREE

‘From Small Things (Big Things One Day Come)’

16

As I did more and more voice-overs, I came to look on Soho as my second home. It was an easy, good life and I would often arrive early at a session to make the most of the very generous hospitality on offer, reading the newspapers and magazines and raiding the bowls of sweets and chocolates. Once I had munched my way through the free confectionery and wandered, slightly heavier, along to the studio, I would invariably be told by the people from the advertising agency (almost exclusively comprising a female producer and male creatives, giving the impression of an indulgent mother showing off her gifted sons) how much ‘everyone in the office’ had enjoyed my demo tape; they’d all been laughing their heads off.

What a funny guy!

For a while, this was sufficient. It was enough just to be doing the voice-overs; it sated the hunger I had for performance that wasn’t being satisfied by any decent roles on television or film. And the praise from the ad execs was very nice too, thank you. After a while, though, it was as if I was outgrowing it and I began to have a tangible feeling – as strange as it sounds, not unlike the feeling I’d experienced when I first knew that I wanted children – of needing to go to the next level.

I had, in my own way, been making baby steps towards stand-up for a while now. When I was working on

Xposure

, I would entertain the crew between takes with seemingly spontaneous bits of business which, in reality, I’d been trying out for some time on as many people as possible. The material was going down well, and I began to visualize myself performing it onstage, in front of a paying audience. As the demo tape was proving such a hit, it seemed perfectly logical to simply perform it live at a comedy club and wait for the wave of riotous laughter to begin.

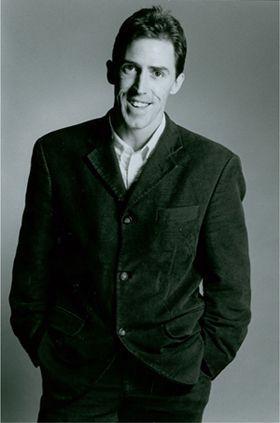

My stand-up suit. About as funny as my act.

The first step towards performing at a comedy club is to get what’s known as an ‘open spot’. This is a short, usually five-minute set on that night’s bill, unpaid and most times introduced to the audience as just what it is, i.e. a new comedian trying to get a foot on the bottom rung of the ladder. This policy of full disclosure lowers the audience’s expectations and, depending on the type of club, will encourage either a sympathetic ear and large helpings of the benefit of the doubt or a viciously cruel mob, baying (or in my case

baa-ing

, but more on that later) for blood. Pretty much every successful comedian you’ve ever laughed at will have gone through this terrifying process. Getting an open spot is not easy, especially in London where there are long waiting lists. At some clubs hopeful comics can be kept waiting for up to a year or more, just for the chance to get up on the stage and do five minutes. Being inherently lazy, I phoned the club nearest to my house, the Bearcat in St Margaret’s, and was given a date some months down the line.

The next step was to learn my tape off by heart. It consisted solely of impressions. I’ve since lost the cassette, but from memory they included Mark Little from

The Big Breakfast

, Chris Barrie in his

Brittas Empire

incarnation, Hugh Grant, Rolf Harris, Arnold Schwarzenegger, the cast of

Red Dwarf

and a little routine featuring Henry Kelly on his daytime television quiz,

Going for Gold

.

‘Gunter, Helmut, Jean-Pierre and Dave … Who am I? Born in Ireland, I’m an annoying twa–’

Buzz!

‘Helmut?’

‘Err, you are Henry Kelly, no?’

I learned it quite easily – by now it was very familiar to me – and when the day finally came round, I set off confidently for the club. The Bearcat is undoubtedly one of the nicer comedy venues. Run by James Punnett and Grahame Limmer, it’s in what to all intents and purposes appears to be a classic village hall or scout hut, behind the Turk’s Head pub. Removable seating is lined up in rows, there’s a bar at the back, a stage at the front, and an aisle down one side. Behind the stage are two tiny rooms, inside one of which the artist stands and waits nervously before making an entrance and beginning their act. I was a little bit anxious, but deep down felt sure that my collection of impressions would go down a storm, just as they had on the tape. I was introduced by James and walked out, smiling at the crowd as I ambled towards downstage centre, took the microphone out of its stand and began.

It only took twenty seconds to realize that the audience hadn’t made up their minds about me yet. It took another ten to realize that they had, after all, made up their minds, and the newly made-up minds had decided I wasn’t up to much. They didn’t laugh. At all. Worse than that, they didn’t heckle either. With a heckle, at least you have something to work with, something to bounce off. They just sat there in silence, staring at me with blank faces. If I detected anything from them, it was a hint of sympathy. Nothing I said was getting a response.

Nothing.

I hadn’t expected this; at worst, I thought I’d get weak laughter, just a few titters. But here I was, completely dying in hushed funereal silence. While continuing to trot out the memorized act, in my mind I was panicking.

What the hell am I going to do?

I had been so confident that this evening was to be the beginning of a new chapter in my career. It had seemed like the natural next step; everyone kept telling me how funny I was, and how I really ought to do stand-up. I couldn’t take in how badly it was going.

Things then became worse as my mental anguish took on some physical properties in the form of a dry mouth. When I say a dry mouth, I don’t mean a slightly dry mouth, I mean a completely arid, cracked riverbed, drought-ridden dry mouth. Along with this my tongue seemed to be getting bigger and began to stick to my dried-out mouth, which made performing the impressions almost impossible. I couldn’t form the sounds for the words needed to speak as myself, let alone as Hugh Grant, the master of bumbling charm. I desperately tried to moisten my mouth. One way to do this is to bite your tongue; I bit mine so hard I let out a little yelp of pain, which the audience assumed was yet another unfunny moment in a consistently unfunny act.

Nothing worked.

The dry mouth as a result of nerves problem is one that has stayed with me to this day, although thankfully it happens far less now. But it still occurs. Sometimes it’ll be when I know I’m unprepared for something and not getting the laughs I want. But also, more worryingly, it can happen when things are going OK. It’ll sometimes just begin, and I’ll have to try to trick my body into relaxing and my mouth into releasing moisture. If you ever come to see me onstage and I begin to make strange shapes with my mouth – like a horse eating a mint – then you’ll know I’m not happy and I’m trying to get some moisture into my mouth.

If I had wanted to do an impression of the Elephant Man then things would have been fine, but I didn’t, and they weren’t. It got to the point where I literally couldn’t get any coherent words out and so, having made the rookie’s mistake of taking to the stage without a glass of water, I had to ask a girl in the front row if I could have some of her pint. She of course obliged, and so I had to bend down in silence to get the drink, take a few sips from it, and then regain my composure and carry on performing to the big wall of silence that was wrapping itself around me and squeezing out my last drop of self-belief. It probably took no more than five to ten seconds to take a sip of her drink, but it felt like longer than forever, played out to the backdrop of the deafening quiet. I pushed on through to the end of my act, then quickly left the stage to scattered showers of politely sympathetic applause.

When a gig has gone badly, I like to leave the venue as quickly as possible, avoiding the embarrassment of looking anyone directly in the eye. A bad gig does two things to you. In the long term, it makes you better; you really do learn from your mistakes, and it does thicken your skin to know that you’ve survived a bad show and carried on to fight another day. It enables you to look at a difficult audience and think,

No problem, I’ve had far worse than you

. But in the short term, it can be very damaging.

After this first disastrous attempt, I didn’t return to the stage for a whole year, I was that traumatized by it. It upset me hugely to think that I could have been so wrong in my opinion of my abilities, that I could have misjudged the picture so wildly. I limped back, bruised and battered, to the lucrative and comfortable world of voice-overs. Here, amongst the bowls of sweets, I was a success and could continue to perpetuate and luxuriate in the received wisdom that if I did at some point decide that I had the time to do stand-up, I’d be very bloody funny indeed.