Small Wonder

Authors: Barbara Kingsolver

Small Wonder

Illustrations by Paul Mirocha

To treat life as less than a miracle is to give up on it.

W

ENDELL

B

ERRY

Lorestan Province, Iran: He was crying from hunger, she had milk. Small wonder.

Grand Canyon, Thanksgiving 2001: The things we want are not the end of the world.

The bronze-eyed possibility of lives that are not our own.

The Huachuca leopard frog calls (as if he knew what was out there) from underwater.

El que quiera azul celeste, que le cueste:

If you want the blue sky, the price is high.

The luckiest crab on Sanibel Island, 1997.

Jaguar consuming a human heart, stone panel from post-classical Chichén Itzá.

When all at once there came a crowd.

April, the sexiest month: broad-billed hummingbird.

Attention, everybody: Free breakfast.

The week's essentials, Washington County Hardware.

Dance of combat for female rattlesnake favor.

Peace crane, Hiroshima Memorial.

“When you have to go there, they have to take you in.”

If traveling with small children, secure your own mask first.

I

learned a surprising thing in writing this book. It is possible to move away from a vast, unbearable pain by delving into it deeper and deeperâby “diving into the wreck,” to borrow the perfect words from Adrienne Rich. You can look at all the parts of a terrible thing until you see that they're assemblies of smaller parts, all of which you can name, and some of which you can heal or alter, and finally the terror that seemed unbearable becomes manageable. I suppose what I am describing is the process of grief.

I began this book, without exactly knowing I was doing so, on September 12, 2001. Someone from a newspaper had asked me to write a response to the terrorist attacks on the United States the day before. When you ask a novelist for a response, especially to something so immensely horrible, you had better sit down and wait awhile for the finish. I wrote my piece, then another one, and another. Sometimes writing seemed to be all that kept me from

falling apart in the face of so much death and anguish, the one alternative to weeping without cease. Within a month I had published five different responses to different facets of a huge event in our nation's psychologyâlittle pieces that helped me see the thing whole and try to bear it. I kept going. Soon I understood that I was examining aspects of life that seemed a world away from the World Trade Center towers or the Pentagon, but a world away is exactly where this grief begins and ends. This is a collection of essays about who we seem to be, what remains for us to live for, and what I believe we could make of ourselves. It began in a moment but ended with all of time.

The years since I last published an essay collection, in 1995, have been important ones in the ways of the world, and also in the ways of my family. I've given birth to my second child; the statistical makeup of the earth's population has moved from being mostly rural to mostly urban; wars have ended and wars have begun. I've been moved to write about each of these things, with increasing urgency, while taking into account all the others. Most of these essays are very new, but some have been published before in a different form. Three of themâ“The Patience of a Saint,” “Seeing Scarlet,” and “Called Out”âwere originally cowritten with my husband, Steven Hopp, as assignments for natural history magazines. These and other essays that began as short op-ed or magazine pieces inhaled and expanded to new girths when I offered them the chance to appear in a book. All of the previously published pieces have been partly or largely rewritten to take into account more recent events and to allow them to fit properly side by side in a collection. Some anomalies remain from their disparate origins; notably, I refer often to my children as my toddler, my kindergartner, my ten-year-old, and so on, as if I actually had an infinite number of offspring spanning all ages from birth to about fifteen. Strictly speaking, I have only two children, and this book is not about them; they just happened to be standing nearby

while I looked for illumination, and so they cast their moving shadows.

This book isn't meant to be a commentary on specific political policies, though inevitably the day's headlines, like my children and all the other notable stuff of my life, have provided for me anecdotal entry into issues of more general and enduring interest. The several pieces that open and close the book respond most directly to current events, while many of the others form a collection of parables and reveries on parts of the world that may seem at first very distant from the epicenters of global crisisâa village at the edge of a Mexican jungle, for example, or my daughter's chicken coop. I ask the reader to understand that these essays are not incidental. I believe our largest problems have grown from the earth's remotest corners as well as our own backyards, and that salvation may lie in those places, too.

Compiling this book quickly in the strange, awful time that dawned on us last September became for me a way of surviving that time, and in the process I reopened in my own veins the intimate connection between the will to survive and the need to feel useful to something or someone beyond myself. In fact, that is a theme that runs through the book. Writing, which was both painful and palliative for me, turned out to be my own way of giving blood in a crisis. I can only hope this unit of words will have a longer shelf life than the forty-two days of a unit of blood, as this critical time blends seamlessly into the next one. I have tried to address, ultimately, things that don't rapidly change.

Some of the books that helped inform my writing here would constitute a good reading list for the new millennium:

Guns, Germs and Steel,

by Jared Diamond;

Eco-Economy: Building an Economy for the Earth,

by Lester R. Brown;

Earth in the Balance,

by Al Gore;

Shattering: Food, Politics and the Loss of Genetic Diversity,

by Cary Fowler and Pat Mooney;

Stolen Harvest: The Hijacking of the Global Food Supply,

by Vandana Shiva;

No Logo,

by Naomi Klein;

When Corporations Rule the World,

by David C. Korten;

Open Veins of Latin America,

by Eduardo Galeano;

Blow-back, The Costs and Consequences of American Empire,

by Chalmers Johnson;

This Organic Life,

by Joan Dye Gussow; and anything by Wendell Berry.

Royalties from this book will help support the work of Physicians for Social Responsibility, Habitat for Humanity, Environmental Defense, and the humanitarian-aid project called Heifer International. I thank you on their behalf for the donation you've made, and encourage your continued support. Internet addresses for these organizations appear in the acknowledgments.

I dedicate this book to every citizen of my country who has suffered bereavement with honor, trepidation without panic, and the insult of fundamentalist condemnation without succumbing to similar thinking in turn. We may yet show the world we are worth our salt.

O

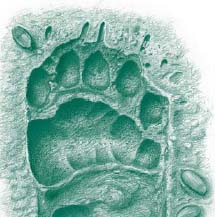

n a cool October day in the oak-forested hills of Lorestan Province in Iran, a lost child was saved in an inconceivable way. The news of it came to me as a parable that I keep turning over in my mind, a message from some gentler universe than this one. I carry it like a treasure map while I look for the place where I'll understand its meaning.

I picture it happening this way: The story begins with a wife and husband, nomads of the Lori tribe in western Iran, walking home from a morning's work in their wheat. I imagine

them content, moving slowly, the husband teasing his wife as she pulls her shawl across her face, laughing, and then suddenly they're stopped cold by the sight of a slender figure hurrying toward them: the teenage girl who was left in charge of the babies. In tears, holding her gray shawl tightly around her, she runs to meet the parents coming home on the road, to tell them in frightened pieces of sentences that he's disappeared, she has already looked everywhere, but he's gone. This girl is the neighbor's daughter, who keeps an eye on all the little ones too small to walk to the field, but now she has to admit wretchedly that their boy had strong enough legs to wander off while her attention was turned toâwhat? Another crying child, a fascinating insectâa thousand things can turn the mind from this to that, and the world is lost in a heartbeat.

They refuse to believe her at firstâno parent is ever ready for thisâand with fully expectant hearts they open the door flap of their yurt and peer inside, scanning the dim red darkness of the rugs on the walls, the empty floor. They look in his usual hiding places, under a pillow, behind the box where the bowls are kept, every time expecting this game to end with a laugh. But no, he's gone. I can feel how their hearts slowly change as the sediments of this impossible loss precipitate out of ordinary air and turn their insides to stone. And then suddenly moving to the fluttering panic of trapped birds, they become sure there is still some way out of this cageâhere my own heart takes up that tremble as I sit imagining the story. Once my own child disappeared for only minutes that grew into half an hour, then an hour, and my panic took such full possession of my will that I could not properly spell my name for the police. But I could tell them the exact details of my daughter's eyes, her hair, the clothes she was wearing, and what was in her pockets. I lost myself utterly while my mind scattered out, carrying nothing but the search image that would locate and seize my child.

And that is how two parents searched in Lorestan Province.

First their own village, turning every box upside down, turning the neighbors out in a party of panic and reassurances, but as they begin to scatter over the rocky outskirts it grows dark, then cold, then hopeless. He is nowhere. He is somewhere unsurvivable. A bear, someone says, and everyone else says No,

not

a bear, don't even say that, are you mad? His mother might hear you. And some people sleep that night, but not the mother and father, the smallest boys, or the neighbor's daughter who lost him, and early before the next light they are out again. Someone is sent to the next village, and larger parties are organized to comb the stony hills. They venture closer to the caves and oak woods of the mountainside.

Another nightfall, another day, and some begin to give up. But not the father or mother, because there is nowhere to go but this, we all have done this, we bang and bang on the door of hope, and don't anyone dare suggest there's nobody home. The mother weeps, and the father's mouth becomes a thin line as he finds several men willing to go all the way up into the mountains. Into the caves. Five kilometers away. In the name of heaven, the baby is only sixteen months old, the mother tells them. He took his first steps in June, a few weeks before Midsummer Day. He can't have walked that far, everybody knows this, but still they go. Their feet scrape the rocky soil; nobody speaks. Then the path comes softer under the live oaks. The corky bark of the trees seems kinder than the stones. An omen. These branches seem to hold promise. Lori people used to make bread from the acorns of these oaks, their animals feed on the acorns, these trees sustain every life in these mountainsâthe wild pigs, the bears. Still, nobody speaks.

At the mouth of the next cave they enterâthe fourth or the hundredth, nobody will know this detail because forever after it will be the first and lastâthey hear a voice. Definitely it's a cry, a child. Cautiously they look into the darkness, and ominously, they smell bear. But the boy is in there, crying, alive. They move into

the half-light inside the cave, stand still and wait while the smell gets danker and the texture of the stone walls weaves its details more clearly into their vision. Then they see the animal, not a dark hollow in the cave wall as they first thought but the dark, round shape of a thick-furred, quiescent she-bear lying against the wall. And then they see the child. The bear is curled around him, protecting him from these fierce-smelling intruders in her cave.

I don't know what happened next. I hope they didn't kill the bear but instead simply reached for the child, quietly took him up, praised Allah and this strange mother who had worked His will, and swiftly left the cave. I've searched for that part of the storyâwhether they killed the bear. I've gone back through news sources from river to tributary to rivulet until I can go no further because I don't read Arabic or Farsi. This is not a mistake or a hoax; this happened. The baby was found with the bear in her den. He was alive, unscarred, and perfectly well after three daysâand well fed, smelling of milk. The bear was nursing the child.

What does it mean? How is it possible that a huge, hungry bear would take a pitifully small, delicate human child to her breast rather than rip him into food? But she was a mammal, a mother. She was lactating, so she must have had young of her own somewhereâpossibly killed, or dead of disease, so that she was driven by the pure chemistry of maternity to take this small, warm neonate to her belly and hold him there, gently. You could read this story and declare “impossible,” even though many witnesses have sworn it's true. Or you could read this story and think of how warm lives are drawn to one another in cold places, think of the unconquerable force of a mother's love, the fact of the DNA code that we share in its great majority with other mammalsâyou could think of all that and say, Of course the bear nursed the baby. He was crying from hunger, she had milk. Small wonder.

Â

The story of the child and the bear came to me on the same day I read the year's opening words on the bombing campaign in Afghanistan. I sat very still at the table that morning while my coffee went cold and my eyes scanned one sentence after another, trying to absorb the account of explosives raining from the sky on a place already ruled by terror, by all accounts as poor and warscarred a populace as has ever crept to a doorway and looked out. My heart was already burdened by grief; only days had passed since I sat in this same place, at the same time of day, and listened to a report that unfolded unbelievably, numbingly, into a litany of unimaginable terror and assault on this country that holds my love and life. I could hardly bear more. But now my mind's eye ran away to find women on the other side of the world who were looking just then from their children up to the harrowing skies. What would they make of this message, whose retaliatory import seemed so perfectly clear to us? I read that the bombs had taken, among others, four humanitarian-aid workers in the small office in Kabul that coordinated the work of removing land mines from the soil of that beleaguered nation. My heart's edge felt as dull and pocked as an old shovel as it scooped low to take on this new weight, the rubble and grief of war. And so when I came to the opposite page in the book of miracles, I cleaved hard to this other story. People not altogether far away from Kabulâwrapping themselves in similar soft robes, similar hopesâhad been visited by an impossible act of grace.

In a world whose wells of kindness seem everywhere to be running dry, a bear nursed a lost child. The miracle of Lorestan is genuine. If you venture onto the information highway with a good search engine and propose “Kayhan, Iran, bear,” you will find this tiny, remarkable note in the human archive. You may also find, as I did, a report written by Heshmatollah Tabarzadi, telling how he and eleven other Iranian students heading home after a rally were arrested and tortured for protesting against government oppres

sion. His story comes up in the search because it was reported in Kayhan, and buried deep in the text are the words of an officer who told him during one of his strenuous torture sessions, “We can milk roosters here, bears lay eggs here, you?! You're just a human being. In the course of one hour we can make a bear confess to being a rabbit.” Another small footnote in the human archive. God is frightful, God is greatâyou pick. I choose this: God is in the details, the completely unnecessary miracles sometimes tossed up as stars to guide us. They are the promise of good fortune in a cloudless day, and the animals in clouds; look hard enough, and you'll see them. Don't ask if they're real.

I elect to believe that the Lori men didn't kill the bear. For years to come I will picture the father quietly lifting the boy from her belly, wrapping him in the soft cloth of his shirt, and reverently leaving the cave of his salvation. Leaving a small pile of acorns outside the lair of this mother, this instrument of Allah's design, as a sacrament.

I believe in parables. I navigate life using stories where I find them, and I hold tight to the ones that tell me new kinds of truth. This story of a bear who nursed a child is one to believe in. I believe that the things we dread most can sometimes save us. I am losing faith in such a simple thing as despising an enemy with unequivocal righteousness. A mirror held up to every moral superiority will show its precise mirror image: The terrorist loves his truth as hard as I love mine; he has a mother who looks on her child with the same fierce pride I feel when I look at my own. Someone, somewhere, must wonder how I could love the boys who dropped the bombs that killed the humanitarian-aid workers in Kabul. We are all beasts in this kingdom, we have killed and been killed, and some new time has come to us in which we are called out to find another way to divide the world. Good and evil cannot be all there is.

Lately we've had to consider a new kind of enemy we can

hardly bear to behold: a foul hatred bent to the destruction of all things precious to usâto

me;

I'll shudder here and speak for myself as someone who loves her life as it is, a woman whose spirit would surely get itself stoned to death if forced to submit to the order of such men. The horrors they've wrought have reduced me at times to a pure grief in which I could only cross my arms against my chest and cry out loud. I can't pretend to understand their aims; I can barely grasp the motives of a person who hits a child, so I surely have no access to the minds of men who could slaughter thousands of innocents and die in the process, or train others to do those things. I presume they want us to become more like themselves: hateful, self-righteous, violent. I expect they would count themselves victorious to see us reduced to panic under their specter, to fall into factions of difference and censor or attack our own minorities, to weaken and let go of the ideals of equality and kindness that first brought our country onto the map of the world. So I hold my own heart fast against the fulfillment of this horrific prophecy, and I hope that the men who constructed it can be made to live out humiliated ends in prisonâa punishment that would inspire fewer followers, I think, than dramatic death in battle.

But even that would not be the end of the story. This new enemy is not a person or a place, it isn't a country; it is a pure and fearsome ire as widespread as some raw element like fire. I can't sensibly declare war on fire, or reasonably pretend that it lives in a secret hideout like some comic-book villain, irrationally waiting while my superhero locates it and then drags it out to the thrill of my applause. We try desperately to personify our enemy in this way, and who can blame us? It's all we know how to do. Declaring war on a fragile human body and then driving the breath from itâthat is how enmity has been dispatched for all of time, since God was a child and man was even more of one.

But now we are faced with something new: an enemy we can't

kill, because it's a widespread anger so much stronger than physical want that its foot soldiers gladly surrender their lives in its service. We who live in this moment are not its causeâinstead, a thousand historic hungers blended to create itâbut we are its chosen target: We threaten this hatred, and it grows. We smash the human vessels that contain it, and it doubles in volume like a magical liquid poison and pours itself into many more waiting vessels. We kill its leaders, and they swell to the size of martyrs and heroes, inspiring more martyrs and heroes. This terror now requires of us something that most of us haven't considered: how to defuse a lethal enemy through some tactic more effective than simply going at it with the biggest stick at hand.