Smuggler Nation (10 page)

Authors: Peter Andreas

Tags: #Social Science, #Criminology, #History, #United States, #20th Century

Eight supply ships secured through Deane’s clandestine dealings with Beaumarchais brought some two thousand tons of desperately needed supplies for the Continental Army in 1777.

27

The ships

carried eight thousand seven hundred and fifty pairs of shoes, three thousand six hundred blankets, more than four thousand dozen pairs of stockings, one hundred and sixty-four brass cannon, one hundred and fifty-three carriages, more than forty-one thousand balls, thirty-seven thousand fusils, three hundred and seventy-three thousand flints, fifteen thousand gun worms, five hundred and fourteen thousand musket balls, nearly twenty thousand pounds of lead, nearly one hundred and sixty-one thousand pounds of powder, twenty-one mortars, more than three thousand bombs, more than eleven thousand grenades, three hundred and forty-five grapeshot, eighteen thousand spades, shovels, and axes, over four thousand tents, and fifty-one thousand pounds of sulphur.

28

The vessels

Amphitrite

and

Mercure

, which carried “more than eighteen thousand stands of arms complete, and fifty-two pieces of brass cannon, with powder and tents and clothing, reached Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in the spring in season for the campaign of 1777.”

29

According to one Deane biographer, “It is impossible to exaggerate the importance of those supplies in the battles which culminated in the fall of British General Burgoyne, who was sweeping down powerfully from Canada to New York with the purpose of separating the northern from the southern colonies.”

30

These clandestine shipments are widely credited as decisive in the defeat of the British at Saratoga in October 1777, a key turning point in the Revolution leading to France’s formal entry into the war.

31

As the historian C. H. Van Tyne puts it, although the battle of Saratoga was “won by American soldiers,” it was also “won with ammunition and guns of which ninety per cent were obtained through French channels.”

32

Just a few months earlier, in July

1777, General Philip Schuyler wrote to Washington from Saratoga that his “prospect of preventing them [the British] from penetrating is not much. They have an army flushed with victory, plentifully provided with provisions, cannon, and every warlike store. Our army … is weak in numbers, dispirited, naked, in a manner, destitute of provisions, without camp equipage, with little ammunition, and not a single piece of cannon.”

33

All of this would change with the influx of smuggled military supplies, much of it procured by Deane.

34

Only one of the smuggling ships launched by Deane and Beaumarchais, the

Seine

, was captured en route after unloading part of its cargo at Martinique. The ship had false papers directing it to the French island of Miquelon, but the British seized it after finding hidden papers—which the pilot and captain failed to destroy in time—indicating the real destination. Yet even this loss had a silver lining for the revolutionary cause: implicating the French in violations of neutrality was damaging to Anglo-French relations, which American leaders hoped would accelerate France’s entry into the war.

35

Even though Deane was good at making covert deals for war supplies, he was notoriously bad at keeping track of his receipts and expenses, leading to accusations of financial fraud, abuse, and personal enrichment. Apparently, both Deane and Beaumarchais used the cover of purchasing supplies as an opportunity to also line their own pockets.

36

Recalled from Paris, Deane ended his career as an arms broker in a cloud of controversy; he was later branded a traitor for advocating reconciliation with Britain and rejoining the empire.

Wartime profiteering was even more starkly at play in the realm of privateering, which itself was intimately intertwined with smuggling. The shifting geography of war shaped the business of war. Britain’s initial occupation of Boston gave a competitive advantage to Providence-based privateering and smuggling. And Providence shipping, in turn, was negatively affected by the British occupation of Newport in December 1776. Business subsequently boomed in Boston once the British withdrew and the city recovered from occupation, and it was especially advantaged by the British occupation of New York. At least 365 ships of Boston were commissioned as privateers during the Revolution.

37

The privateer investor John R. Livingston was so impressed by Boston’s bustling wartime harbor that he worried

that peace, “if it takes place without proper warning, may ruin us.”

38

James Warren lamented the privateering-induced changes in Boston: “Fellows who would have cleaned my shoes five years ago have amassed fortunes and are riding in chariots.”

39

Privateering helped to create “the Revolution’s nouveau riche.… Their future heirs would exemplify American old money at its most genteel.”

40

For instance, the sailor Joseph Peabody rose from deckhand to investor through nine successful voyages between 1777 and 1783. He became Salem’s leading shipping magnate, with more than eighty vessels and eight thousand employees. Similarly, Israel Thorndike, who started out as a humble cooper’s apprentice, became a skipper on a privateer ship; he would later become one of New England’s wealthiest bankers and textile manufacturers.

41

Privateering also enriched the Cabots of Beverly: the firm owned by John and Andrew Cabot became one of the most lucrative in Massachusetts.

42

As in the earlier Seven Years War, colonial merchants signed up to take advantage of privateering—except now they were commissioned to subvert rather than serve the British Empire. From the British perspective, they were therefore criminals and pirates (and defined as such in the Pirate Act of 1777); but they also became George Washington’s de facto private navy. The war at sea was at least as important as the war on land, yet for the colonies it was fought almost entirely by what was essentially a profit-driven mercenary force. Though there were only a handful of Continental Navy ships, several thousand privateering ships set sail during the course of the American Revolution.

43

They rarely could take on the Royal Navy, but they wreaked havoc on supply lines by targeting British merchant vessels.

At the same time, there was a serious downside to relying on a loot-seeking private naval force. For example, the few Continental Navy vessels that existed had great difficulty attracting able seamen, given the higher rewards from signing on with privateering vessels.

44

Many navy servicemen deserted to work on privateering ships, wooed by the prospect of loot.

45

The financial allure of privateering was captured in new sea chanties: “Come all you young fellows with Courage so Bold / Come Enter on Bord and we will cloth you with gold....”

46

Following orders was also a challenge for some privateers. They did not always distinguish between friendly and enemy ships in

their attacks.

47

And prisoners captured were supposed to be used for prisoner exchanges, but at times they were instead ransomed at sea. Benjamin Franklin dispatched the privateering vessels

Black Prince

,

Black Princess

, and

Fear Not

from France with the explicit mission of capturing men to use for prisoner exchanges. Franklin was outraged when he discovered that the captains of these vessels, who had been recruited from the ranks of Irish smugglers, were instead trading captured prisoners for ransom money.

48

Privateering was also a high-stakes investment opportunity for colonial elites. Among them was Nathanael Greene from Rhode Island, who discreetly invested in privateering ventures on the side while serving as quartermaster general in the Continental Army. Hinting at some ethical unease and reputational concerns about his privateering investment ventures, Greene’s private correspondence expressed the desire that his efforts to cash in on the Revolution remain a secret. He wrote to an associate in 1779: “By keeping the affair secret I am confident we shall have it more in our power to serve the commercial connection than by publishing it.”

49

Greene even proposed using a fictitious name, suggesting that “This will draw another shade of obscurity over the business and render it impossible to find out the connection.”

50

Suspecting that Greene was also involved in diverting public funds for his own private business ventures, the Continental Congress attempted to investigate—only to be blocked by General Washington on the grounds that it would undermine military morale.

51

Meanwhile, without acknowledging the slightest hypocrisy, Greene denounced John Brown of Providence, charging him and others of enriching themselves while army officers sacrificed for the revolutionary cause.

52

Similarly, the wealthy Philadelphia businessman Robert Morris wrote to his partner William Bingham in Martinique in December 1776: “I propose this privateer to be one third on your account, one third on account of Mr. Prejent and one third on my account. I have not imparted my concern in this plan to any person and therefore request you will never mention the matter.” Just a few months earlier he had written to Silas Deane: “Those who have engaged in Privateering are making large Fortunes in a most Rapid manner. I have not meddled in this business which I confess does not Square with my Principles.”

53

By the spring of 1777, Morris had become so enthused about privateering that he not only urged Bingham “to increase the number of my engagements in that way …” but also wrote, “it matters not who knows my concern.”

54

More than any other individual, Morris was in charge of the business side of the war. He headed the Secret Committee of Trade, created by Congress in September 1775 to covertly procure supplies from abroad.

55

Morris used his business contacts in Europe to help supply the Continental Army and later became known as the “financier of the American Revolution.”

56

Much of the activities of the Secret Committee of Trade went through his own company, Willing and Morris. His business attitude toward the Revolution is summed up in a message to Deane: “It seems to me the oppert’y of improving our Fortunes ought

not to be lost, especially as the very means of doing it will contribute to the Service of our Country at the same time.”

57

For Morris, being a patriot and a profiteer was the same thing.

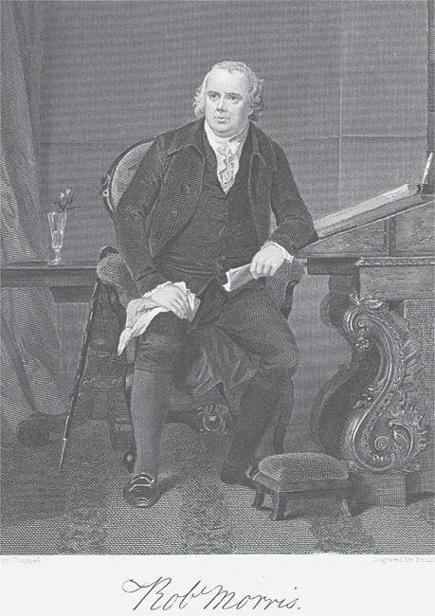

Figure 3.1 Robert Morris (1734–1806), politician, signer of the Declaration of Independence, and “Financier of the American Revolution.” Morris organized the clandestine effort to supply American rebels through smuggling networks to the Caribbean and Europe (Corbis).

Privateering was not simply predatory; it contributed to the exchange of scarce goods in wartime, diverted British supplies to supply colonial forces, and intersected with smuggling in multiple ways. Benjamin Franklin encouraged privateers to sell their captured prizes in French ports—a form of illicit trade that violated French neutrality and outraged the British.

58

Complaints from London were met by French promises to crack down, but the captured goods continued to be smuggled in. The smuggling methods included use of false papers to disguise the origins of the goods, off-loading cargoes onto French ships at sea, and selling captured prizes just beyond the harbor, thus technically outside French waters.

59

Franklin penned formal apologies to the French for the infractions, helping them publicly save face with the British and keep up appearances even as they continued to tolerate and outright encourage the clandestine trade. Franklin wrote to Congress in September 1777: “England is extremely exasperated at the favor our armed vessels have met with here. To us, the French court wishes success to our cause, winks at the supplies we obtain here, privately affords us very essential aid, and goes on preparing for war.”

60

Indeed, at one point French officials informed port authorities at Le Havre and Nantes that they should cease their embarrassing inquiries about suspicious goods headed for the West Indies.

61