Smuggler Nation (40 page)

Authors: Peter Andreas

Tags: #Social Science, #Criminology, #History, #United States, #20th Century

Figure 13.2 “National Gesture.” Political cartoon depicts the many hands that take bribes during Prohibition (American Social History Project, City University of New York).

Mayor Fiorello La Guardia was apparently not corruptible, but it didn’t matter. “I just don’t understand that guy [La Guardia],” the bootlegger Charles “Lucky” Luciano told his ghost writers. “When we offered to make him rich he wouldn’t even listen.… So I figured: what the hell, let him keep City Hall, we got all the rest, the D.A., the cops, everything.”

19

La Guardia had little faith in Prohibition, claiming that it would take 250,000 cops to enforce it in New York—and that an additional 250,000 would be needed to police the police.

20

Public support for enforcement was undermined by political hypocrisy, nowhere more evident than in the nation’s capital, which was supposed to be the model of dry urban America. Not only was the capital city dripping wet but so too was the Capitol Building. In October 1930, the

Washington Post

ran a series of front-page stories written by George Cassiday, who claimed to have worked as a bootlegger for Congress for a decade, at one point taking orders and distributing booze right out of a storeroom in the House Office Building. He said he filled between twenty and twenty-five orders per day and calculated that four out of five senators and congressmen drank.

21

When the police raided one local bootleg operation they discovered account books with the names of many congressmen and senators as regular customers. The White House also turned out to be squishy wet: the duties of the treasurer of the Republican National Committee apparently included making sure President Warren G. Harding’s regular poker games had plenty of whiskey on hand.

22

Mabel Walker Willebrandt, who stepped down as deputy attorney general in 1928, wrote a year later: “I think that probably nothing has done more to disgust and alienate honest men and women who originally strongly favored the prohibition amendment and its strict enforcement than the hypocrisy of the wet-drinking, dry-voting congressmen.”

23

Journalist H. L. Mencken called these congressmen “wet dry”—“a politician who prepared for a speech in favor of Prohibition by taking three or four stiff drinks.”

24

Willebrandt complained that

many “have been antagonized by the discovery that the very men who made the Prohibition law are violating it and that many officers of the law sworn to enforce Prohibition statutes are constantly conspiring to defeat them. How can you justify prison and fines when you know for a fact that the men who make the laws and appropriate the money for Prohibition are themselves patronizing bootleggers?” It was well known, she said, that “Senators and Congressmen appeared on the floor in a drunken condition,” and that “bootleggers infested the halls and corridors of Congress and ply their trade there.”

25

Some congressmen who had voted to toughen penalties for violating the Volstead Act even turned out to be petty smugglers; several were caught trying to sneak alcohol into the country in their luggage on return trips from abroad.

26

Particularly embarrassing was the arrest of Ohio Congressman Everett Denison, one of the most outspoken supporters of Prohibition, for attempting to smuggle in a barrel of rum while returning from a Caribbean cruise.

27

Meanwhile, enforcement became increasingly overwhelmed and overloaded. The swamped federal courts resorted to large-scale plea bargaining to clear liquor cases on what came to be called “bargain days.” In exchange for pleading guilty and waiving the right to a trial by jury, defendants avoided jail time and received a minimal fine. But even with massive plea bargaining, prisons were overflowing with Prohibition law offenders, prompting President Herbert Hoover to build six new federal penitentiaries. During Hoover’s term, the number of Prohibition offenders in prison almost doubled.

28

Toughening penalties in response to the failures of enforcement, as Congress did in passing the punitive Jones Act of 1929, only made matters worse by further clogging the criminal justice system.

29

It also backfired, angering the public and turning key early supporters of Prohibition, prominent among them William Randolph Hearst and John D. Rockefeller Jr., against it.

There were some much-touted law enforcement success stories, most notably the conviction of America’s most famous gangster, Al Capone. For years openly flouting the law and bragging about his bootlegging exploits in the press, he had simply become too famous for his own good. His highly publicized conviction on tax-evasion charges was a defining moment in the history of the U.S.

federal taxing agency. Indeed, historian Michael Woodiwiss suggests that no one benefited more from the rise and fall of Al Capone than the Internal Revenue Service. An ex–IRS agent later wrote than in the aftermath of Capone’s conviction “tax violators began to kick in, right and left … floods of amended and delinquent returns, with checks attached, showing up not only in Chicago but at other Internal Revenue offices all across the country from scared tax cheaters.”

30

Enforcement also succeeded in shutting down the saloon—which had come to symbolize urban America’s drinking problem and was the main target of the Anti-Saloon League—only to see it quickly replaced by the less visible, and therefore less publicly offensive, speakeasy. Alcohol use did decline by roughly a third; America sobered up, at least a bit, and especially at the beginning (it would take decades for consumption to return to the pre-Prohibition level). The price of a drink skyrocketed. In some northern urban markets, a fifteen-cent cocktail in 1918 became a seventy-five-cent cocktail in the early 1920s. Many working-class drinkers simply could not afford this.

31

But many others could, and demand remained strong enough to sustain a vast market.

It was precisely the Prohibition-induced high prices—and thus the potential for extraordinarily high profits—that made violating the law so attractive to moonshiners, bootleggers, and rumrunners. In other words, the very success of Prohibition in raising prices was also the source of its own undoing. The high financial stakes are also what made the illicit trade so violent—with such trouble mostly concentrated in a handful of major urban markets such as Chicago and New York—and so attractive to a particularly aggressive class of criminal entrepreneurs.

There were many sources of domestic supply, ranging from homemade moonshine to diverted industrial alcohol to pre-Prohibition stockpiles and even doctor prescriptions. But the largest source—and by far the highest-quality—were illicit imports shipped in by boat, car, truck, train, and airplane, and then watered down for even higher profits. The Atlantic seaboard and northern border were the two most important entry points for the illicit alcohol that helped keep dry America wet.

Rum Row

Nassau was in the right place at the right time. Just as it was a conveniently located base and warehouse for British-supplied blockade runners during the American Civil War, it served a similar function during the Prohibition era. Prohibition turned Nassau into a smuggling boomtown and depot for U.S.-bound liquor. Much of the supply came from British distillers, who used the island to illicitly access an otherwise closed U.S. market. Complaints from Washington to London fell on deaf ears. Winston Churchill in the Colonial Office took the stance that “a State is only responsible for the enforcement of its own laws” and thus refused to impede the Bahamas trade in order to help the United States enforce Prohibition—a law he described as “an affront to the whole history of mankind.”

32

The Bahamas imported only about five thousand quarts of liquor in 1917, but this increased to about 10 million quarts a year by the end of 1922.

33

And what was good for the liquor trade was also good for government coffers. The government collected six dollars in export duty on every case of liquor passing through its port. Liquor revenue skyrocketed from $44,462 in 1918 to $984,732 in 1921.

34

A Bahamian economic development brochure noted that the government’s financial good fortune was due to “the conditions supervening in the United States early in 1920.”

35

The British governor of the colony, Sir Bede Clifford, even went so far as to suggest that it would be fitting to build a monument honoring Andrew J. Volstead near the statues of Queen Victoria and Columbus.

36

The real moneymakers in Nassau, Daniel Okrent points out, were not the smugglers themselves but the assortment of brokers and their financial backers who made the trade possible. The profiteers of Prohibition included, for example, Roland Symonette, who by 1923 had become a millionaire from investing in the liquor trade and who would later go on to serve as premier when the Bahamas became self-governing. Knighted by Queen Elizabeth II, his portrait now appears on the Bahamian fifty-dollar bill.

37

Nassau not only warehoused liquor but also provided legal cover for American rumrunners by registering their ships as British. From 1921 to 1922 there was a tenfold increase in the net tonnage of vessels with

Bahamian registry.

38

Flying the British flag made American smuggling ships immune from U.S. seizure in international waters. As long as the vessels stayed beyond the three-mile limit of U.S. territorial waters, the Coast Guard could not touch them.

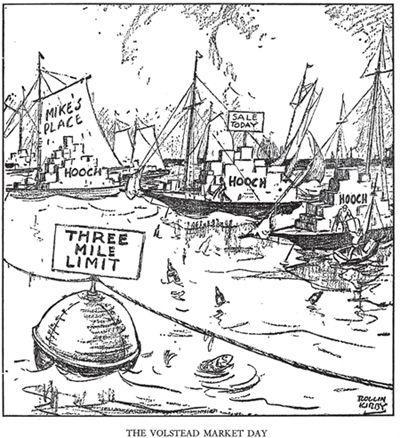

Figure 13.3 “The Volstead Market Day.” Rollin Kirby’s political cartoon of “Rum Row,” the floating marketplace set up by bootleggers just beyond the three-mile limit of U.S. territorial waters.

New York World

, 1923 (Granger Collection).

What consequently developed came to be known as Rum Row: fleets of liquor-laden ships (very little of it rum, actually) idling just outside the three-mile limit, not far from U.S. urban markets. There were in fact many rum rows, located off of Boston and New York in the North and off of Galveston, New Orleans, Mobile, Tampa, Savannah, and Norfolk in the South. As the largest market, New York attracted the highest concentration of rumrunners.

39

These smuggling flotillas—essentially floating liquor stores—would transfer their supplies to smaller boats darting out and back from the mainland.

40

A bottle of Scotch purchased at Rum Row could be sold for twice as much once landed—and that

was before cutting with water and grain alcohol to boost profits even further. U.S. authorities claimed that during a twelve-month period in the mid-1920s more than three hundred foreign-flagged ships were involved in “wholesale and organized efforts to smuggle liquor into the United States,” with almost all of them flying the British flag.

41

The tiny French possession of St. Pierre-Miquelon, some fifteen miles south of Newfoundland, became Nassau’s chief competitor as a smuggling depot and Rum Row supplier. The island, the last remnant of the French empire in North America, offered many of the same advantages as Nassau but at a much cheaper price, imposing a levy of only about forty cents per case.

42

The island also became a warehouse for Canadian distillers, who could officially claim they were exporting to France. In 1923, St. Pierre handled more than half a million cases of liquor, with about one thousand vessels passing through its small port. So much booze flowed through St. Pierre that locals developed a creative form of recycling: most of the homes constructed on the island during the Prohibition years were built using empty whiskey cases.

43

The former Florida boat maker Bill McCoy is credited as the pioneering founder of the first rum row, off Long Island, making him America’s most well-known and even celebrated rumrunner. McCoy used Nassau as his supply base during his early runs, and later he was allegedly the first to use St. Pierre. The term the “Real McCoy” came to signify a high-quality, genuine product “right off the boat” (though the actual origins of the term remain disputed). McCoy prided himself on being an “honest lawbreaker” and independent operator, and he got out of the business as it became much more organized and violent after the mid-1920s. The story of his rise and exit illustrates the transformation of the rumrunning business itself. It also illustrates the perils of becoming a celebrity rumrunner. Prohibition enforcers could not put smuggling out of business, but with enough effort they could put high-profile smugglers such as McCoy out of business if their reputation and visibility made them too much of a public nuisance and embarrassment. McCoy spent eight months in a New Jersey jail—though the warden had such a lax attitude that he let McCoy stay at a nearby hotel and even “escape” for evening outings, allegedly including to attend a boxing match at Madison Square Garden.

44

McCoy retired from smuggling after his release from prison.