Smuggler Nation (48 page)

Authors: Peter Andreas

Tags: #Social Science, #Criminology, #History, #United States, #20th Century

The national panic over the spread of crack cocaine made the drug war an even more potent issue in electoral politics. As

Congressional Quarterly

commented: “In the closing weeks of the congressional election season, taking the pledge becomes a familiar feature of campaign life. Thirty years ago, candidates pledged to battle domestic communism.… In 1986, the pledge issue is drugs. Republicans and Democrats all across the country are trying to outdo each other in their support for efforts to crush the trade in illegal drugs.”

102

Senator John McCain spoke for many in Congress: “This is such an emotional issue—I mean, we’re at war here—that voting no would be too difficult to explain,” McCain said of Senate efforts to increase the military role in the drug war in 1988.

103

Meanwhile, as America’s war on cocaine was ramping up, cocaine was quietly becoming entangled in a very different sort of war in Central America: the campaign by U.S.-backed Contra rebels against Nicaragua’s Sandinista government. A three-year congressional investigation revealed that some of the same CIA-contracted air transport companies covertly hired to fly supplies to the Contras were also involved in transporting drugs. Although the nature and extent of CIA knowledge and involvement remains murky and steeped in controversy, the available evidence indicates that individual Contras, Contra supporters, and Contra suppliers exploited their political protections as a convenient cover for drug-trafficking operations.

104

A variation on this dynamic was simultaneously playing out in Afghanistan, where CIA-backed insurgents battling the Soviets were also involved in cultivating and smuggling opium poppies to help fund their political cause. Washington was apparently well aware of the situation but turned a blind eye in pursuit of larger geopolitical goals. “We’re not going to let a little thing like drugs get in the way of the political situation,” explained a Reagan administration official at the time. “And when the Soviets leave and there’s no money in the country, it’s not going to be a priority to disrupt the drug trade.”

105

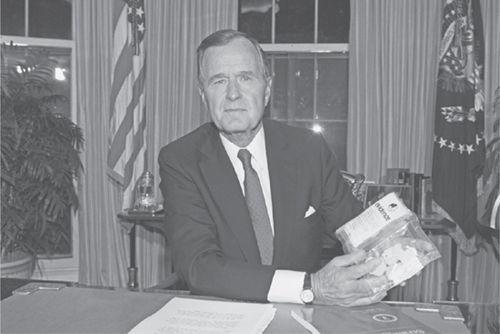

Militarization

The war on drugs was ramped up even further by Reagan’s successor, George H. W. Bush, including drafting the military to take on a more frontline antidrug role. In his first prime time televised address to the nation, on September 5, 1989, President Bush held up a bag of crack cocaine. For added shock value, he announced that it had been bought across the street from the White House, in Lafayette Park—though he failed to mention that a bewildered drug dealer had to be lured there by undercover agents to make the buy. The president set the tone: “This is the first time since taking the oath of office that I felt an issue was so important, so threatening, that it warranted talking directly with you, the American people,” the president began. He quickly declared a national consensus on the primacy of the issue—“All of us agree that the gravest domestic threat facing our nation today is drugs”—and then declared war, calling for “an assault on every front.” Urging Americans to “face this evil as a nation united,” Bush proclaimed that “victory over drugs is our cause, a just cause.” Bush proposed that “we enlarge our criminal justice system across the board.… When requested, we will for the first time make available the appropriate resources of America’s armed forces.” The president called for a $1.5 billion increase in domestic law-enforcement spending in the drug war and $3.5 billion for interdiction and foreign supply reduction.

106

A

Washington Post

/ABC News poll taken after Bush’s speech indicated that 62 percent of those polled were willing to give up “a few of the freedoms we have in this country” for the war on drugs. Eighty-two percent said they were willing to permit the military to join the war on drugs.

107

Bush took unprecedented steps to widen the drug-fighting authority of federal agencies. To a degree unmatched by previous presidents, he used his power as commander in chief to draft the U.S. military into the drug war, elevating what had been a sporadic and relatively minor role in assisting in civilian enforcement into a major national security mission for the armed forces. In the fall of 1989 Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney declared drugs to be a high-priority mission of the Department of Defense. The fiscal 1989 National Defense Authorization Act charged the Defense Department with three new responsibilities. It was made the lead agency for detecting drug traffic into the country;

given responsibility for integrating all command, control, and communications for drug interdiction into an effective network; and told to approve and fund state governors’ plans for using the National Guard in interdiction and enforcement. Funding for the military’s drug-enforcement activities increased from $357 in 1989 to more than $1 billion in 1992.

108

Figure 14.6 President George H. W. Bush displays a bag of crack cocaine evidence during his first televised address to the nation, September 5, 1989 (Bettmann/Corbis).

The Pentagon became noticeably more enthusiastic about taking on drug war duties as the Cold War came to an end. A former Reagan official in the Pentagon commented: “Getting help from the military on drugs used to be like pulling teeth. Now everybody’s looking around to say, ‘Hey, how can we justify these forces.’ And the answer they’re coming up with is drugs.”

109

One two-star general observed in an interview, “With peace breaking out all over it might give us something to do.”

110

The Pentagon inspector general found that a large number of officers consider drug control “as an opportunity to subsidize some non-counternarcotics efforts struggling for funding approval.”

111

In 1990, for example, “the Air Force wanted $242 million to start the central sector of the $2.3 billion Over-the-Horizon Backscatter radar

network. Once a means of detecting nuclear cruise missiles fired from Soviet submarines in the Gulf of Mexico, Backscatter was now being sold as a way to spot drug couriers winging their way up from South America.”

112

Military equipment and technologies initially designed to deter military invaders were increasingly made available and adapted to deter drug law evaders. For example, Airborne Warning and Control System surveillance planes began to monitor international drug flights; the North American Aerospace Defense Command, which was built to track incoming Soviet bombers and missiles, refocused some of its energies to tracking drug smugglers; X-ray technology designed to detect Soviet missile warheads in trucks was adapted for use by U.S. Customs to find smuggled drugs in cargo trucks; researchers at Los Alamos Laboratory, the birthplace of the atomic bomb, started developing sophisticated new technologies for drug control; and the Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency began using its research on antisubmarine warfare to develop listening devices to detect drug smugglers.

113

Drug enforcement came to define post–Cold War U.S. security relations with many of its southern neighbors. Reflecting the new priorities, the U.S. Southern Command in Panama was transformed into a de facto forward base for drug interdiction. In 1989 the U.S. military was authorized to make arrests of drug traffickers and fugitives on foreign territory—without the approval of the host country.

114

Drug control even provided the official rationale for the military invasion of Panama and the indictment of Panamanian General Manuel Noriega on drug-trafficking charges, no doubt the most expensive drug bust in history. Although U.S. intelligence reports connecting Noriega to drug trafficking went back as far as 1972, Washington tolerated and overlooked Noriega’s shady dealings until he was no longer politically useful.

115

The intelligence community was also drafted to take on a more frontline drug war role. In 1990 the CIA announced that “narcotics is a new priority.”

116

Some observers no doubt found this rather ironic, given that the agency had since its creation shown a chronic willingness to subvert the fight against drugs in the name of fighting communists. The most high-profile example of the CIA’s new hands-on antidrug role

was the 1992–93 manhunt to help the Colombian government track down and eliminate the drug trafficker Pablo Escobar.

117

Back home, meanwhile, the drug war was both transforming and overloading the criminal justice system. Fighting drugs was the main driver in the adoption of military models, technologies, and methods (including the proliferation of SWAT teams) in domestic law enforcement.

118

At the same time, the criminal justice system was increasingly overwhelmed with drug cases. By 1990 drug cases accounted for an astonishing 44 percent of all criminal trials and 50 percent of criminal appeals. A dramatic increase in the number of Americans imprisoned made the United States the world’s number one jailer, and much of the overload was a consequence of the war on drugs. Drug offenders as a proportion of inmates in federal prisons increased from 25 percent in 1980 to 61 percent in 1993.

119

Bush’s “drug czar,” William Bennett, was an especially forceful advocate of the administration’s hard-line rhetoric and punitive approach, telling a national radio audience that he saw nothing morally wrong with beheading drug traffickers.

120

The Clinton administration toned down the drug war rhetoric of his predecessors but did little to actually change drug laws or redirect federal drug-control agencies. A proposal to move the DEA, a product of Nixon’s drug war, into the FBI was scrapped after generating intense pushback from both the DEA and members of Congress. A modest proposed cut to the interdiction budget was not only withdrawn, but a new position, interdiction coordinator, was created by administration officials who were anxious to reassure conservative critics in Congress that they took drug interdiction seriously. The new coordinator (who was also the head of the Coast Guard) immediately began to press for more funding.

121

President Bill Clinton moved drug policy off the political agenda and out of the public spotlight, but the drug war machinery created and built up by his predecessors continued to grind on. As the governor of Arkansas, Clinton had at one point argued for decriminalizing marijuana. But as a president eager to not appear “soft on drugs”—especially after having acknowledged smoking, though not inhaling, marijuana while in college—Clinton never challenged the marijuana laws that had been significantly toughened in the 1980s. Marijuana arrests more than doubled during Clinton’s years in office, reaching record levels.

122

Overall, the drug war looked little different from that of the Bush era: in 1990, under Bush, some 1,089,500 people were arrested for drug law violations. In 1993, under Clinton, 1,126,300 were arrested. One hundred and seven metric tons of cocaine and 815 kilograms of heroin were seized in 1990, compared to 110.7 tons of cocaine and 1,600.9 kilos of heroin netted in 1993.

123

Washington’s relations with much of Latin America continued to be driven by drugs, with virtually all U.S. military and police aid to the region provided under the rubric of drug control by the end of the decade. Colombia became the third-largest recipient of U.S. military assistance (behind Israel and Egypt), with the Colombian government using it to blur the distinction between counterinsurgency and counterdrug operations.

The drug war bureaucracy continued to expand. The DEA’s budget went from over $219 million by 1981 to about $800 million under Clinton.

124

And this accounted for only a fraction of the total budget for federal drug-law enforcement, which was more than $8 billion in 1995. Roughly forty federal agencies or programs, in seven of the fourteen cabinet departments, had drug law enforcement responsibilities. Within the Department of Justice alone, the DEA was by the early 1990s just one of fifteen agencies or programs involved in drug control. For instance, the FBI, the Bureau of Prisons, and the Immigration and Naturalization Service all played various drug war roles, from criminal investigations to border checks to prison management. At Treasury, seven agencies had some role in drug enforcement. Customs, for example, was charged with interdicting and disrupting the illegal flow of drugs by air, sea, and land, and the IRS was involved in tracking drug-generated funds and disrupting money laundering. Within the Department of Transportation, the Coast Guard was mandated to eliminate “maritime routes as a significant mode for the supply of drugs to the U.S. through seizures, disruption and displacement.”

125

And the Federal Aviation Administration helped identify “airborne drug smugglers by using radar, posting aircraft lookouts, and tracking the movement of suspected aircraft.”

126

At the Department of Defense, whose mission was to provide “support to the law enforcement agencies that have counterdrug responsibilities,” three new joint antidrug task forces were created.

127

And National Guard units searched cargo, patrolled

borders, flew aerial surveillance, eradicated marijuana crops, and lent expertise and equipment to law enforcement agencies.