Smuggler Nation (55 page)

Authors: Peter Andreas

Tags: #Social Science, #Criminology, #History, #United States, #20th Century

Figure 15.4 President George W. Bush and Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff view a Predator drone in Yuma, Arizona, used to patrol the U.S.-Mexico border, April 9, 2007 (Jason Reed/Reuters/Corbis).

President Obama boasted about the border buildup at a 2010 press conference: “We have more of everything: ICE [Immigration and Customs Enforcement], Border Patrol, surveillance, you name it. So we take border security seriously.”

88

But it was not at all clear what the actual deterrent effect of all this border activity was. Many determined migrants and their smuggler guides continued to be redirected rather than deterred by the new border barriers. This included more “express service” of migrants through ports of entry (hidden in vehicles or through fraudulent use of documents, or simply paying compromised inspectors to look the other way) rather than braving the harsh desert and mountain terrain. There was also a surge in the landing of migrants

on California beaches by speedboat and other low-profile, radar-evading marine craft. Smugglers charged a premium for these faster and more convenient modes of clandestine entry.

89

The continued escalation of enforcement certainly made the border more challenging and dangerous to cross, with hundreds of migrants dying each year. Indeed, the border was harder to cross than ever before in the nation’s history. It was also increasingly difficult to even reach the border, with more and more U.S.-bound migrants (especially the tens of thousands of non-Mexicans traveling through Mexican territory) facing a gauntlet of extortionist criminals and corrupt cops along their northward journey.

Immigration laws were also more stringently enforced than at any other time; federal prosecutions for immigration law violations more than doubled from 2001 to 2005, replacing drug law violations as the most frequently enforced federal crime.

90

By the end of the decade, violations of immigration law represented more than half of all federal prosecutions (and in the Southwest it was more than 80 percent).

91

One consequence was to fuel a booming business in federally funded private detention centers in the Southwest and elsewhere.

92

No doubt the hardening of the border was having some deterrent effect on would-be unauthorized border crossers, given that the crossing was made much more difficult and expensive and the odds of being apprehended and detained increased. Still, most of those migrants caught could simply keep trying until they succeeded. Surveys of migrants indicated that almost all the Mexicans who attempted illegal entry eventually made it in—thanks largely to hiring the services of professional smugglers.

93

Ultimately, the biggest inhibitors to migrant smuggling were not just tougher border enforcement but broader push and pull factors. Demographic, social, and economic shifts within Mexico began to reduce the push to migrate, while at the same time the sharp contraction of the U.S. economy starting in 2007 greatly reduced the pull of employer demand.

94

Just as the economic boom of the 1990s had fueled an enormous influx of illegal workers despite intensified policing efforts to keep them out, the Great Recession discouraged many new migrants from leaving home and even encouraged some to return. Low-wage immigrants were hit particularly hard by the economic downturn,

especially in the construction sector.

95

Following an old historical pattern, as the jobs began to dry up so did the migration flow. There were an estimated 11.2 million unauthorized migrants in the country in 2010—more than half of them Mexican—down from a high of 12 million in 2007 but still higher than the 8.4 million in 2000, and triple the 1990 level of 3.5 million.

96

Meanwhile, the Mexican side of the border had turned increasingly violent and dangerous, much of it fueled by mounting drug-related murders in Mexican border cities. The sharply rising death toll in Juarez, the city most heavily hit, made it one of the most dangerous places in the world. With much fanfare, Mexican President Felipe Calderón declared an all-out war on the country’s major drug-trafficking organizations when he took office in 2006. But even though his military-led antidrug offensive weakened the Tijuana, Juarez, and Gulf trafficking organizations, these “successes” unintentionally created an opportunity for rival traffickers, and the ensuing disorganization, disruption, and competitive scramble to control turf, routes, and market share fueled an unprecedented wave of drug violence in Mexico—with most of the weapons that were used to carry out the killings having been smuggled in from the United States.

97

Applauding Calderón’s drug war offensive, Washington pledged $400 million in counterdrug military and police assistance for Mexico in 2008, and it took on an increasingly active behind-the-scenes role within Mexico. This included setting up a “fusion intelligence center” at a northern Mexican military base (modeled on similar centers in Iraq and Afghanistan for counterinsurgency purposes), providing military and police training for thousands of Mexican agents, and deploying CIA operatives and military contractors to Mexico to gather intelligence, assist in wiretaps and interrogations, and help plan raids and other operations.

98

In early 2011 the Pentagon also began to deploy high-altitude Global Hawk drones deep into Mexican territory on drug surveillance missions.

99

More than ever before, Mexico and the border became the front line of America’s war on drugs.

Yet much to Mexico’s frustration, Washington made only token efforts to curb the clandestine export of U.S. firearms that was arming Mexican drug gangs. Despite Mexico’s complaints, there was little domestic political pressure within the United States—and there were

plenty of political obstacles—to more intensively police and restrict bulk weapons sales (ranging from handguns to AK-47s) by thousands of loosely regulated gun dealers in Texas and elsewhere near the border. In late 2011, J. Dewey Webb, the special agent responsible for curbing gun smuggling in Texas for the Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms, noted that “The United States is the easiest and cheapest place for drug traffickers to get their firearms.”

100

Despite the proximity of the drug violence in Mexico and public anxiety about spillover (remarkably, U.S. border cities continued to have some of the lowest violent crime rates in the country), stopping the southbound flow of arms generated far less attention and concern than the northbound flow of drugs.

101

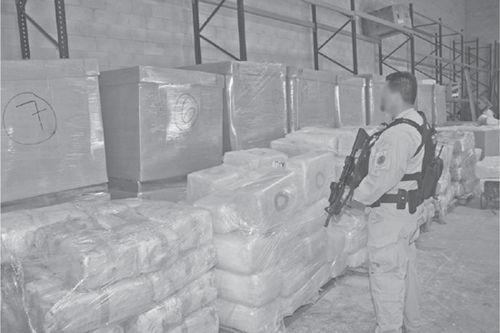

Figure 15.5 Drugs seized from a tunnel discovered under the California-Mexico border, 2011 (Immigration and Customs Enforcement).

Washington provided sophisticated surveillance technology and expertise to help Calderón target and remove a growing number of high-profile traffickers. But as had been the case in eliminating high-level Colombian traffickers in the 1990s, this did not translate into an overall reduction of drug trafficking; in fact, Mexican exports of heroin, marijuana, and methamphetamines to the United States were reportedly increasing at the end of the decade.

102

Rather than greatly reducing the

drug flow, it seemed that the crackdown was doing more to fuel brutal competition within and between a growing number of rival smuggling organizations and creating a much more fluid and volatile—and therefore violent—market environment. Four criminal organizations dominated the trafficking of drugs into the United States when Calderón took office in 2006, but by 2011 there were seven—with the new traffickers even more willing and able to use violence than the old ones. The most trigger-happy and ruthless of the new groups, Los Zetas, was composed of former members of an elite U.S.-trained Mexican military unit.

103

Every year, the drug killings in Mexico continued to mount. By mid-2012, drug-related deaths reached roughly fifty thousand since Calderon launched his antidrug offensive in 2006.

104

And there was no end in sight. Many Mexicans, suffering from drug war fatigue and fed up with the escalating violence, no doubt viewed the bloody battle to feed America’s seemingly insatiable appetite for illicit drugs as yet another affirmation of the old Mexican saying “Poor Mexico, so far from God, so close to the United States.”

EVEN AS THE U.S.-MEXICO

border continued to be ground zero in America’s campaign against the smuggling of people and drugs in the early twenty-first century, Washington also increasingly viewed these clandestine border crossings as part of a much larger, more ominous, and unprecedented globalized crime threat requiring a U.S.-led global response. In other words, the new challenge was not just a porous border but the shadowy underside of globalization more generally. Yet on closer inspection, one cannot help but get a strong sense of historical déjà vu. As detailed in the next chapter, there is at least as much continuity as transformation in this illicit globalization story—and certainly more than is conventionally recognized amid all the uproar over an allegedly new and rapidly growing danger. Indeed, it seems that no policy debate in Washington has been more devoid of historical memory, learning, and reflection.

16

America and Illicit Globalization in the Twenty-First Century

AMERICA IS UNDER SIEGE

, or so we are told. Transnational organized crime “poses a significant and growing threat to national and international security, with dire implications for public safety, public health, democratic institutions, and economic stability,” the White House declared in its 2011

Strategy to Combat Transnational Crime: Addressing Converging Threats to National Security

.

1

Such dire pronouncements had been repeated in Washington policy circles since the 1990s, with U.S. Senator John Kerry exclaiming that America “must lead an international crusade” against a growing global crime threat.

2

Pundits similarly sounded the alarm bells. Jessica Mathews pointed to organized crime and trafficking as the dark side of a fundamental “power shift” away from governments; and Moises Naim boldly labeled the conflict between governments and global crime as “the new wars of globalization,” with governments increasingly on the losing side.

3

Crime has gone global, Naim warned, “transforming the international system, upending the rules, creating new players, and reconfiguring power in international politics and economics.”

4

International relations scholars echoed these sweeping claims of change, even calling transnational organized crime “perhaps

the

major threat to the world system.”

5

One security scholar described transnational organized crime as “the HIV virus of the modern state, circumventing and breaking down the natural

defenses of the body politic.” Most states in the past “seemed to have the capacity” to keep this threat “under control,” but this is “no longer so obviously the case.”

6