Somebody Stop Ivy Pocket (24 page)

Read Somebody Stop Ivy Pocket Online

Authors: Caleb Krisp

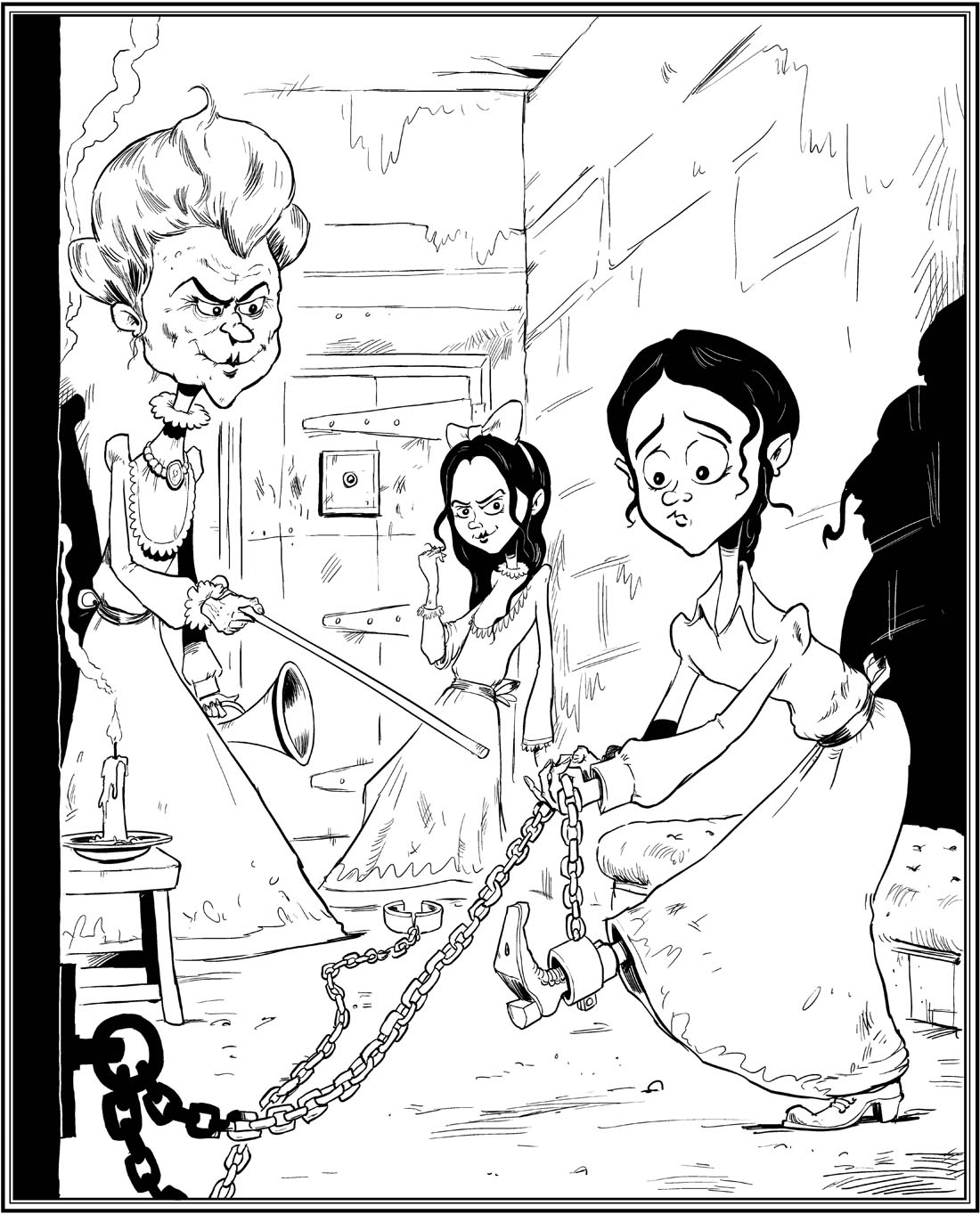

By this stage I was shaking my head. ‘I don’t understand.’

Lady Elizabeth lifted her cane and pointed it at me. ‘You filled Rebecca’s head with dangerous nonsense and I am certain it led to her death. And you destroyed Matilda’s birthday ball, making her the laughing stock of Suffolk. The Butterfield name is now mired in scandal and tragedy and it is all because of you, Miss Pocket.’

‘Grandmother didn’t think you were stupid enough to fall for our little trick,’ said Matilda brightly, ‘but I promised her that you were.’

‘We’ve had you followed for weeks,’ said Lady Elizabeth with delight.

‘This whole night has been …?’ I didn’t finish the sentence. It was too awful.

‘This whole night has been the beginning,’ said Lady Elizabeth. ‘The beginning of retribution for your sins, Miss Pocket.’

The old bat was just as I remembered her. Head like a walnut. Hands like talons. Bony as a skeleton. Full of fury. Miss Frost had warned me that Lady Elizabeth would direct her venom at me after Rebecca’s death, but I had not taken her seriously.

‘You cannot do this,’ I said. ‘A person cannot be committed to a madhouse without a doctor’s say-so. I have read of such things in perfectly reputable novels.’

Lady Elizabeth huffed. ‘Never read a novel that didn’t make me want to shoot the author with a musket.’ She turned her wrinkled head towards the door. ‘Professor, come!’

I did not know it, but a figure had been listening in the corridor outside, waiting for his cue. He walked briskly into the cell and smiled rather gushingly at Lady Elizabeth.

‘Professor Ploomgate is one of the most respected doctors in the country,’ said Lady Elizabeth, ‘and as I am a member of the board here at Lashwood and a rather

generous

benefactress, he agreed to assess your questionable mental state.’

‘How are you feeling, Ivy?’ said Professor Ploomgate.

‘Never better, dear,’ I said, as sanely as I knew how. ‘Apart from being the victim of a rather vengeful old bat and her hateful granddaughter.’

‘I see,’ said the Professor with a meaningful nod of his head.

He was impossibly grim. Sour expression. Eyes of the green and bulging variety. A forehead so vast and furrowed, it was practically crying out for wallpaper. But as frightful as he appeared, he was a respected doctor and was certain to see through this wicked scheme.

‘Do you speak with ghosts, Ivy?’ he asked next.

‘Only when absolutely necessary,’ was my winning reply.

‘Very interesting.’

‘Now she thinks Rebecca is alive in some other world,’ Matilda added helpfully, ‘and just a short time ago, she told me she had visited there herself.’

The Professor’s bulging eyes threatened to pop clear out of their sockets. ‘The patient said she had travelled to another world?’

‘Perhaps she has,’ said Matilda. ‘There is a necklace she possesses that is rather unusual.’

‘Claptrap!’ barked Lady Elizabeth. She hit the Professor’s shoe with her cane. ‘Is this not proof enough that she’s deranged?’

‘Is this true, Ivy?’ He stepped towards me. ‘Do you believe that you have left this world and reached another?’

The situation was getting rather out of hand.

‘Look, Professor Plumcake,’ I said, ‘I think there has been –’

‘Ploomgate,’ he said tersely. ‘My name is Professor

Ploomgat

e.’

‘Well, that’s not your fault, dear. It’s rather like your forehead – regrettable, but entirely out of your control. Now be a good man and unchain me.’

‘What did I tell you?’ snapped Lady Elizabeth, hitting the Professor’s shoe again. ‘Here is a girl of low rank, a

nobody

, who tells wild stories about herself as easily as she breathes. If that isn’t a sign of mental disorder, I don’t know what is!’

Professor Ploomgate lifted his head. Closed his eyes. Then opened them again and took a sharp intake of breath. ‘In my professional opinion the girl is disturbed.’ He turned and patted old walnut head on the shoulder. ‘You were right to bring her here, Lady Elizabeth.’

‘She only wants to punish me,’ I said urgently. ‘This is about revenge, Professor, not the state of my mind. If you can’t see that, dear, then you’re the mental patient.’

Perhaps this wasn’t the best course of action. The professor walked from the cell, ignoring my loud protests.

‘Come, Matilda, let us go,’ said Lady Elizabeth.

‘Wait,’ said the girl.

She stepped close to me and I could see the hunger in her eyes. ‘Where is it, Pocket?’

And I knew just what she meant. The horrid girl searched my neck. And the pockets of my apron. And my dress.

‘What have you done with it?’ she hissed.

‘Rebecca is alive,’ I whispered, ‘and all you care about is the diamond that took her away. Shame on you, dear.’

Something flashed over her face. It was fleeting. But it was there.

She stomped towards the door. ‘I will meet you in the carriage, Grandmother.’

Lady Elizabeth scowled at me for the longest time. I slid down the wall and sat again. Staring at the opened door. Longing to pass through it and be free.

‘Does it soothe your guilt, Miss Pocket, to imagine that Rebecca has escaped death and lives on in some far-flung world?’ she said curtly.

‘Does it soothe your guilt to lock me up in this place?’

‘Why should I feel guilt?’

I looked up at her without fear. ‘Why were you not kinder? Why did you not try and understand about the clocks, about the piece of her that was missing?’

‘She looked in one piece to me,’ barked Lady Elizabeth. But

she knew

exactly

what I meant. ‘The girl had lost her mother, did she need to lose her common sense as well?’ Her worn face hardened right before my eyes. ‘Rebecca needed a firm hand, not a soft touch.’

‘She needed

you

, dear. But instead of love you showered her with disapproval.’

‘Get comfortable, Miss Pocket,’ said the old bat, lifting her cane once more and pointing it at me, ‘for you are going to be an inmate at Lashwood for a

very

long time.’

There was music in the madhouse. It went on all night. Care of a woman humming – her voice echoing down the empty corridor – no doubt some lunatic locked in another cell. She had just the one tune. And as soon as she finished humming it, she would start again.

Her pitch was perfect, but as that first night stretched on in endless misery, and the tune was repeated again and again, I would gladly have smothered her with my apron.

There were other voices, crowding the silence. Shrieks of lunacy. Wretched sobbing. One fellow called for his mother every ten minutes. Another swore like a pirate and made violent threats.

I spent most of my time trying to lift the veil. Hoping to make the bleak madhouse fall away and Prospa House rise up. But without the Clock Diamond, all I managed to conjure up was a headache.

Being a girl of bright ideas, I then decided to call upon the Duchess of Trinity.

‘I’d like to box your ears for trying to use me

again

for a

horrid revenge,’ I said aloud. ‘But the thing is I’m in rather a pickle, and I was wondering if you could drop in and offer some assistance.’

Nothing. Not even a ghostly cackle.

As the cell was small and wretched, I passed the time in a variety of ways. Sitting was a great favourite. Walking about as far as my chain would allow also figured prominently. Professor Ploomgate had not visited again. The hefty woman in the grimy black and white dress would come with a bowl of gruel. A ladle of water. I did not change my clothes, for I had no others. I did not wash. I did not see the sky. Such was my new life.

Three days passed like this.

Someone new brought the gruel on day four (Saturday, I think – though it was hard to keep track). A boy of about nine or ten. Dark hair. Brown skin. Large hazel eyes. Interesting ears. He came in silently, carrying two buckets, and served me a helping of slop.

As we were only fed twice a day, I ate it as if it were Mrs Dickens’ finest porridge. When I had scraped the very last dregs from the wooden bowl, I wiped my mouth on my sleeve and handed it back to him.

Then the boy did something most extraordinary. He filled the bowl with another helping of gruel. As if that were not enough, he then pulled a piece of stale bread from his pocket and handed it to me!

‘You wouldn’t happen to have a few uncooked potatoes in there, would you?’ I said, biting into the bread and savouring its crusty goodness.

He looked at me strangely. As if eating raw potatoes required an explanation.

‘I’m a tiny bit dead,’ I said between mouthfuls, ‘and it’s had rather a strange effect on my appetite.’

‘Blimey,’ he replied, clearly impressed. ‘I’ll see what I can rustle up tomorrow.’

‘Have you worked in this ghastly place long?’

‘Just started this week. Pay’s terrible, but there’s plenty to eat and I can sleep down in the cellar most nights.’

‘You sleep here?’

‘When I have to.’

‘What’s your name, dear?’

‘Jago,’ was his answer. ‘If you’re being official like, I’m

Oliver

Jago, but it’s a rotter of a name, so I chucked it.’

I used the last of the bread to mop up the gruel. ‘I knew an Oliver once. An orphan, of course, with hideous eating habits.’ I shoved the bread in my mouth and chewed it feverishly. ‘He was always asking for

more

. Which is frightfully bad form.’

A bell sounded from somewhere up above us, signalling the end of dinner.

Jago picked up the buckets. ‘See you tomorrow, I guess.’

‘Yes, dear, I’ll be waiting.’

The boy stopped and looked back at me.

‘You’re awful young. What you in for then?’

‘Revenge,’ was my answer.

He shrugged. ‘Good a reason as any.’

I began to look forward to Jago’s visits most eagerly. He took to calling me chatterbox. Can’t think why. And would always give me extra gruel and bread. Even the odd potato (lovely boy!). In the few minutes we had, Jago would tell me of life outside – where he had gone around London foraging for an extra penny or two. He never said anything about his family. I assumed because he didn’t have one.

Being a shy sort of girl, I was reluctant to speak about myself. But slowly I came out of my shell (not unlike a sea turtle) and told him a few snippets from my wondrous adventures. He seemed terribly impressed.

As he was taking his leave one evening, the humming lady’s endless melody rolled in like an afternoon breeze. A very

annoying

breeze.

‘I’m to feed her next,’ he said eagerly. ‘She’s right mad, she is.’

‘Doesn’t she know any other tune?’

‘Hums it for the baby,’ explained Jago. ‘“Sleep and Dream, my Sweet”, it’s called.’

I gasped. ‘Of course, it’s a lullaby.’

‘Matron says she’s been here for years.’

‘And she has a baby?’

‘Not here, she don’t.’

‘Jago, would you be a dear and ask Professor Ploomgate to stop by? I rather fear he has forgotten about me and I’m rather keen to get out of this beastly cell. You see, I’m not at all deranged.’

The boy thought on it a moment then said, ‘Sorry, chatterbox, they’d chuck me out on my ear if I made a racket about one of you lot.’