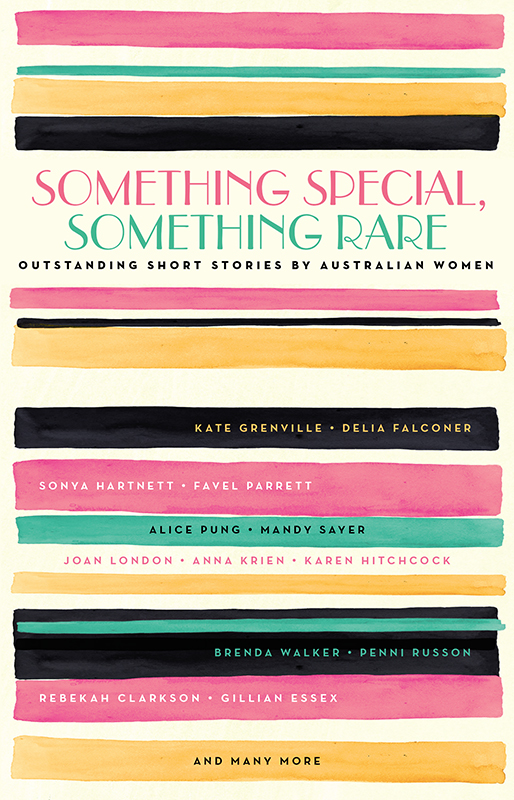

Something Special, Something Rare

Read Something Special, Something Rare Online

Authors: Black Inc.

Published by Black Inc.,

an imprint of Schwartz Publishing Pty Ltd

37â39 Langridge Street

Collingwood VIC 3066 Australia

email:

[email protected]

Copyright © 2015 Black Inc.

Individual stories © retained by authors, who assert their rights to be known as the author of their work

A

LL

R

IGHTS

R

ESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

The National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Something special, something rare: outstanding short stories by Australian women / Various authors.

9781863957298 (paperback)

9781925203233 (ebook)

Short stories, Australian

Australian fiction â Women authors.

A823.01

Book design by Peter Long

CONTENTS

MANDY SAYER

The Meaning of Life

PENNI RUSSON

All That We Know of Dreaming

TEGAN BENNETT DAYLIGHT

J'aime Rose

BRENDA WALKER

That Vain Word No

FIONA MCFARLANE

The Movie People

KAREN HITCHCOCK

Forging Friendship

DELIA FALCONER

The Intimacy of the Table

BUSHFIRE

KATE GRENVILLE

The radio said that Mindurra was in

no immediate danger,

but the television had a different message. There were pictures of walls of flame flickering and leaping up into trees.

Ringed by fire

was a phrase the journalists seemed to like. Against the ragged angry blaze, ant-like silhouetted figures scurried ineffectually, flapping wet bags and squirting water from backpacks.

No immediate danger.

Louise repeated the words to herself. But Mindurra was such a little place, with hillsides of bush all around. It was easy to imagine a fire swallowing it down without missing a beat. As she walked down Homer Street towards the shops, brown smoke hid the contours of the hills over in the distance and smudged the sky. After a term at Mindurra Public School she had got used to seeing the hills, always there at the end of Homer Street. It was unsettling to have lost them now.

They were hoping for a change in the wind. A man from the Weather Bureau had come on and pointed at isobars with a ruler, but he had not committed himself on the matter of a change in the wind.

With the town in crisis, it had seemed the right thing for the new teacher to offer to help. But Valda in the school office had looked doubtful.

Got any First Aid, love? She had asked. Class B licence? Anything like that?

Valda did not want to be rude, but it seemed that the only place for a person without such skills was down in the Country Women's Association Hall, helping with the sandwiches.

Grand Street, Mindoro, did not normally generate a lot of traffic, but today as Louise turned the corner, there was quite a bottleneck: three cars and a lorry, and then one of the old red fire trucks from the Volunteer Bush-Fire Brigade. A man on the back, half-hidden among hoses and tanks, lifted a hand to her, but he took her by surprise and by the time she waved back, the truck had gone.

She thought it could be that Lloyd. The one who'd bought her a cup of tea at the Picnic Races.

Valda had more or less made him do it: she loved to matchmake. Valda had already tried to set her up with her cousin from Gulargambone, and then with the man from the Pastures Protection Agency. Neither event had been a success.

Lloyd had agreed willingly enough, but she felt herself going stony. She had sat at the wobbly table in the Refreshments Tent, staring into her cup of powerful Ladies' Auxiliary tea, watching Lloyd stirring the sugar into his. Behind her, she could feel everyone skirting around them â Valda, and Mrs Mitchell the principal, and John the man from the garage. They were ostentatiously not watching. It was like grown-ups leaving children alone to

make friends.

It never worked. She could have told them that. It didn't work with kids and it wasn't going to work any better with two wary frumps past their prime.

Frump:

that was how she thought of herself. She knew how she looked: too big, too plain, and with that uncompromising set to her mouth. This Lloyd was a frump, too, with his ears that stuck out, his big freckled face, his awkward smile, the way he kept fiddling with his spoon. They were two of a kind, but the wrong kind.

She'd always hated being paired off, hated the way people thought you'd be grateful. No one seemed to realise that a failed marriage wasn't like a broken plate. You didn't just go out and get another one.

Lloyd seemed no more comfortable than she was, but with the whole of Mindurra watching them sideways, they felt obliged to exchange some information about themselves. It turned out that Lloyd was something with the Water Board. He was here to check the reservoir.

As conversational material, Louise felt this was less than promising.

Oh, the Water Board, she said, and heard it as the other kind of

bored,

the one that they both seemed to be experiencing there and then. She hurried on before she could laugh.

Been with them for long?

It was only to be polite.

Few years, he mumbled, and it seemed as if that was going to be that, but he suddenly blurted out:

Take Mozart!

Pardon? She'd had to say.

Dead of typhoid at thirty. Just think â if they'd had decent water! Another six symphonies!

He was radiant at the thought of it.

Yes, she'd managed to say, feeling the startled look on her face, hearing it in her voice.

I wanted to write music, he said. But Dad thought I ought to go into something solid.

He cleared his throat unnecessarily, glanced at her. She was too much taken by surprise, could not rearrange the muscles of her face into a more welcoming expression in time.

So here I am.

He picked up the spoon and made a big show of putting sugar in his tea and stirring it, even though he'd already put two spoonfuls in before. Her mouth refused to make any of the encouraging sounds she wished to make.

And now he was blushing through his pale freckled skin.

Even his neck was blushing. And his ears. She had never seen such a blush. It was like ink spreading through water. She looked at where his shirt opened at the neck, where she could glimpse soft fair skin that the sun had never roughened. She caught herself wondering how far down the blush went.

Then he met her eye, and a funny thing happened: she felt herself blushing as well. It was ridiculous. There was nothing to blush about. She was angry with herself for blushing, and with this man, for watching her. He was not bold, but he was paying attention. She tried to take a sip of tea, to stop him looking, but the tea was scalding, and only added heat to her blush.

She had no reason to blush: it was just her skin doing it. It was as if her skin and his were having a conversation with each other, all by themselves.

*

Down in the Hall it was all sandwiches and hearsay. It was so hot up at the fire, they said, that you could fry an egg on the front of the truck. A fireball had jumped right across the highway, from the top of one tree to another. The paint had been burned off the number-one fire truck as neatly as with a blowtorch.

Mrs Cartwright, mother of Lee-Anne in second class, was mass-producing the sandwiches. It was easy to see she had done it before, for other fires, for floods, for any kind of disaster requiring sandwiches. Her hands moved quickly and deftly among the bread, the wrapping-paper, the beetroot and shredded lettuce. Her finished parcels were as smooth as little pillows.

Being the novice, Louise was given plain cheese to do. You would think you could not go wrong with plain cheese. But she forgot to put the wrapping paper under first, so the wrapping took twice as long. Or, when she cut them in half at the end, she cut through the paper as well. Her finished packages were lumpy, and unravelled as soon as you let go of them.

She imagined the fire-fighters, sitting on the running board of the fire truck eating the sandwiches. Lloyd would be there, perhaps picking shreds of sliced wrapping paper out of his. She did not think he was the sort to laugh at a failed sandwich, but someone else might.

A man with a soot-dark face, his eyes bloodshot, rushed in to pick up a load of food. He took a sandwich in each hand and spoke with a wild look in his eyes.

Not bloody burning, he was insisting. Bloody exploding!

His hands flew out, demonstrating, and a baked bean landed in Louise's bowl of cheese.

We lost two last time, Mrs Cartwright said, her face gone grim. The wind changed on them.

She laid out another couple of flaps of bread.

They said it looked like they'd tried to run. Dropped the backpacks and that. But you can't outrun a fire.

Louise had seen the fire trucks standing in their garage.

They were very shiny, with the words

Mindurra Volunteer Bush-Fire Brigade

in fancy letters on the doors, and some kind of coat-of-arms thing. They were picturesque, but now that she thought about it, she saw that they were picturesque because â to put it bluntly â they were old. They'd be a disaster. Stalling, boiling over, every trick in the book.

So what should you do? Louise asked. She'd learnt that city people were expected to ask the stupid question.

You find a little dip in the ground, Mrs Cartwright said, and get something over your head, a bag or whatever. It does go over real quick.

She glanced at Louise.

You'd be inclined to give running a go, but, wouldn't you?

It was easy to imagine how it would happen. There would be a few of you working in a line. You'd be flapping away with your wet bags and your little squirters, but the fire would suddenly come up at you from behind. Its size and power would make the idea of wet bags and squirters absurd. You would shout to each other and climb aboard the truck, but it would not start.

You would have just a few moments, after you saw it was hopeless and before the fire got you. There would be no time to think any great thoughts or to review the shortcomings of your behaviour. There would be no point in scribbling a note to anyone. In the moment before the breath was sucked out of your lungs, you might turn and hide your face in the person beside you. In that moment of extremity, it would not matter who it was.

The idea that a man who checked reservoirs for the Water Board might have once wanted to write music had seemed nothing more than ridiculous, that day in the Refreshments Tent. Now, watching her hands automatically buttering bread, she saw how interesting it was that his way of going into something solid had been to go into water.

At the time it had seemed merely silly. It occurred to her now that it could be a kind of heroism.

*

One of her ex-husbands had made a hobby of apocalypse. He'd done a chart in coloured pens, extrapolating forward from the fifteenth century, and had announced that another big war was due any time. He was ready. He kept a knapsack packed ready in the garage, with a compass and a knife and something he called iron rations. At the weekends he ran up and down hills, and practised lighting a fire with a magnifying glass and two dry leaves.

If the bomb drops, he had told her, and we get separated, I'll meet you at Gunnedah Post Office. It's far enough out to be safe.

Gunnedah Post Office, she had repeated, but doubtfully.

Don't forget.

She had not forgotten. But if a bomb dropped, she did not think she would go to Gunnedah Post Office. He would have made other plans now, with some other woman.

And he was not the man she would want to find, in the event of apocalypse.

She did not really know anything about the man who'd gone into water because it was solid. Lloyd. From the Water Board. That was all she knew about him: that, and the way he had of looking at you with a kind of intensity, as if wondering.

She hardly knew him, had only met him the once. She did not have any arrangement with him about the steps of Gunnedah Post Office. Or anywhere else. Why was there, all at once, an emptiness, thinking that it might be too late now to have any arrangement with him, of any kind, about anything at all?

She had got the hang of the sandwiches now. She was churning them out, fast, faster, as if racing the fires eating up the bush. He would not be burned alive. He would come back down as he had gone up, perched in among the hoses, and she would be ready for him this time. He would wave, and she would be there, waving back. Then, perhaps, they could continue the conversation that their skins, so much wiser than they were themselves, had already begun.