Something's Rising: Appalachians Fighting Mountaintop Removal (21 page)

Read Something's Rising: Appalachians Fighting Mountaintop Removal Online

Authors: Silas House and Jason Howard

I speak from a faith perspective when I speak about it. To me, from the faith perspective, we have been given a great gift. God's given us a gift, this marvelous place—and I'm biased, I

know, but I think that Appalachia is the most beautiful place in the world.

For every gift you're given, you're also given a responsibility. Our responsibility is to be stewards, and that's clear. That green-letter Bible is going to let everybody know right where those phrases are in the Bible. But I mean, it's just as simple as Psalm 24—“the earth

is

the Lord's.” It says it really clearly. And there are a host of other verses.

That's speaking as a Christian, but if you want to speak as a parent, why in the world would you want to hand down something to your children that's not at least as good as what you were given, but is hopefully better than what you were given? That flies in the face of everything that most parents intuitively know.

One of the ways that I did get into this issue kind of sideways is that it grew out of air pollution and talking about passing things down to the next generation. My daughters are ninth-generation Tennesseans, and they both have asthma. Neither their dad nor I have asthma. They've both battled just to breathe sometimes. The doctor looked at me and said, “Your daughters will never be healthy as long as they live in this valley. They'll never be completely healthy unless you leave.” And I looked at him and said, “My family's lived in this valley for over 250 years.”

What have we done that in one generation we can go from having air to breathe to not? That's horrifying to me. So to me, it's an issue that strikes at the very heart of family and who we are here in Appalachia, and even if you think the mountains are expendable, our children's lungs aren't expendable.

We've got to find a better way. That's also a huge part of this issue: even if you can look at a mountain and not think it's the prettiest thing in this world, there's this whole other level of this issue that people need to be aware of, and I think by pointing out both sides of that we can make a bigger tent and get more people into it. It just kills me to think that my kids may have to move away.

When you look at something as horrific as mountaintop removal,

there are really not words—and as a writer there really ought to be words—to describe how I feel when I stand in front of a mountain that's not there and to know that destruction occurred as partly my fault, because I'm a consumer of electricity just like everybody is, so I have a part in that. That hurts. That's painful. But partly because we have this short-term way of looking at everything, I think, in this country, that short-sightedness that we have not been able to step out beyond immediate profit, immediate gratification, what's good for our generation and not what's good for later generations. And to me, that's really, truly what sin is: when you can't look outside yourself and see what's good for other people.

I'm Christian, probably mainstream to fairly liberal Christian. I tend to vote Democratic, I tend to think of myself as a progressive, but I realized when working on this legislation that pigeonholing people like that to me feels very wrong. A couple of the staunchest allies in this fight are some of the most conservative Christians in the Tennessee legislature. And they have stepped out of their comfort zones, I think, to some degree, and have taken on this cause and suddenly you realize, “What are all these labels that we put on people?”

I've changed my own thinking on it. One of the most rabid environmentalists can be the most conservative Christian on other issues. I think if I've learned anything from all this, I just absolutely hate this red state–blue state, Republican-Democrat, religious-nonreligious stuff. These labels are all so detrimental to letting us all work together in the ways that we can. Nobody's ever going to agree on everything, but we're letting all these labels keep us apart in ways they just shouldn't.

It's very, very difficult to be involved in an issue that does create so much anger and frustration and divisiveness in people when, first of all, that's not the way I want to move through life and it's not the way that I've tried to move through life, but here I am in the crux of this now and it's forcing me to have to learn how to respond to people who are very angry. And a year ago, my

way of responding to that would probably be to just avoid it, and you can't, really, and be effective working on this issue.

So the way my faith has begun to inform this whole dialogue for me is that I have to try to remember that, from a faith perspective—and this is very Quaker—each of us contains the Spirit of God. I believe that firmly. And you have to try to relate to that Spirit in every individual, whichever side of this issue that they're on. So that's the bottom line for me—that's where the faith part comes in.

The way that this issue has informed how I see my faith is that it's forced me to take a stand on something. And while it would be really easy to just say, “You're wrong and I'm going to continue to be angry with you,” my faith tells me I can't do that. “The issue tells me you're wrong and I have to somehow find a way to help you understand without condemning.” Does that make any sense? It's very difficult, and it's all wrapped up together for me. And it's daily. It's daily. Because generally I process fairly slowly, so if I have a confrontation with somebody I have to kind of retreat, go inward, and think about it and try to figure out “Okay, how am I going to phrase that next time? How am I going to do better next time? How am I going to approach that person next time?” And sometimes there isn't a next time, and that's very hard for me. I don't like leaving things unsaid or undone. That's a part of my faith as well.

All of the legislators come from very different faiths. All of them have a particular point of view. And in the Tennessee legislature most of them come from a business perspective, which is very different from the way I have lived my entire life. I would be the world's worst businessperson, because money just does not drive me. Obviously, making a choice to be a freelance writer, money is not an issue. And a phrase I've used all my life that's resonated with me is “Enough is as good as a feast.”

Think about that: in business, there's never enough. So if I'm operating out of “If you have enough, why would you need any more than enough?” and then they're operating out of “You can

never have too much,” we talk at cross-purposes just automatically. It's two totally different ways of looking at the world. So you've got that whole scenario.

So the anger, I think, comes when I feel like they're totally dismissing my way of viewing the world and they feel like I'm totally dismissing their way of viewing the world, and what we're really both trying to do, I think—or at least I know I'm trying to do—is try to honor their way of viewing the world, but try to say to them, “That's not the only way to view the world, and your way of viewing the world is running roughshod over my way of viewing the world.”

So we've got to figure out how to honor both sides without letting one side totally dominate. And certainly in our culture the business model is what dominates and where a lot of the power is, and certainly where most of the money is, and we on the other side have to do a better job of articulating that and also be a means of holding up a different model. And, frankly, that takes a lot of time and energy and effort, and when you're dealing with a legislator, time is one thing you don't have a whole lot of—you get your ten minutes and that's all they have to hear or really want to hear.

It's so funny. You'd think that your faith would inform the issue, but what's happened for me is this issue has informed my faith in ways that I never would have anticipated.

This year's really taught me all of that.

From the beginning, this whole initiative was launched from a faith perspective, and that has made such a huge difference. The other issues I've worked on in the past were only sort of peripheral; faith was peripheral to the issue. This approach on this issue was steeped in that faith from the beginning, so from day one it was about how do we bring faith into this issue, not how do we bring this issue into our faith.

I always try to be optimistic, because it's not totally in our hands. I try not to be naïve, although people accuse me of that sometimes. It's hard for me to look at any human being and believe

that you can't find redeeming parts of them. I just can't see that. I can't walk through the world and not see that everybody's got good in them, so there are no hopeless human beings. So consequently, I can't look at a social justice issue and say that this is a hopeless situation. But I think that because most people in this region really do share a deep-seated love of the land and deep-seated sense of “We're in a special place,” that makes me more hopeful than I would be, maybe even on a lot of other social justice issues.

I think we have this shared commonality of living in this incredible place that we all want to see taken care of. Do we disagree on how taking care of it is going to act itself out? Certainly we do. And will I be able or LEAF be able to save every mountain we'd want to save? No, I doubt that's going to be possible. But are the coal companies going to get every mountain they want? No, I don't think so. So I'm hopeful.

Knoxville, Tennessee, May 9, 2008

Appalachian Patriot

If you're gonna lead my country

If you're gonna say it's free

I'm gonna need a little honesty.

—Ben Sollee, “A Few Honest Words”

No matter that patriotism is too often the refuge of scoundrels. Dissent, rebellion, and all-around hell-raising remain the true duty of patriots.

—Barbara Ehrenreich

It's the beginning of the dreaded dog days of summer on the forks of Troublesome Creek in Knott County, Kentucky. Those gathered at the forks for the Appalachian Writers Workshop, held annually on the hillside campus of the Hindman Settlement School, are exhausted from the intense, day-long sessions.

Twenty or so attendees have gone up the mountainside to gather on the porch of Preece, one of the school's cabin-style dorms, where the night air hangs thick with humidity and revelry. Their songs drift down through the pines—tonight the favorite is Gillian Welch's “Orphan Girl”—and mingle with the drone of crickets, heat bugs, and bullfrogs down by the creek. Many of the group sing along, half-full glasses cradled in their hands, their heads thrown back in laughter, while others join in side conversations, catching up with their literary kin.

Jack Spadaro leans against the porch railing, alone, taking it all in. It's the first time some of his fellow attendees have met him, and they are surprised to find him so shy and soft-spoken—especially after everything they've read about him in the press.

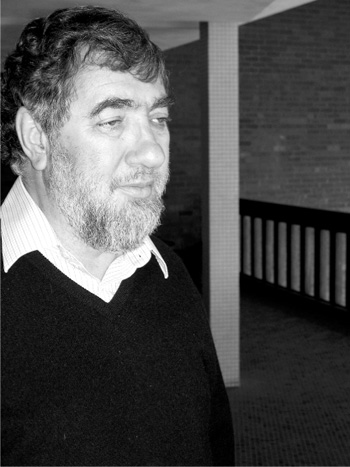

Jack Spadaro, Huntington, West Virginia. Photo by Silas House.

Some drift over to welcome him, saying they're glad that he's now part of the Hindman family, and invite him to join right in. Others steal glances at him over their cups, admiring the quiet man who caused such a ruckus in Washington just a few years before. All are proud to be in his presence, thankful for his defense of fellow Appalachians in nearby Martin County against the moneyed interests of the mining industry and their patrons, the George W. Bush administration and Bush's Secretary of Labor, Kentucky's own Elaine Chao.

Everyone in this group, which represents a rainbow of political positions, all know that true patriotism involves more than yellow ribbons, flag lapel pins, and Lee Greenwood singing “God Bless the U.S.A.” Many modern-day Americans are disdainful of those who actively question their government, believing that doubters beget radicals, radicals beget extremists, extremists beget terrorists. They do not subscribe to the classical definition of patriotism, best articulated by Thomas Jefferson: that dissent is its highest form.

Jefferson would have liked Jack Spadaro. His brand of dissent is the quiet kind—measured, void of shrill chants, tempered by a résumé of government experience a mile long—the sort that makes you hope, down to the marrow of your being, that he is on your side.

His dissent began with a simple refusal to sign his name.

On October 11, 2000, the bottom of a coal slurry impoundment pond gave way in Martin County. Three hundred million gallons of black sludge chugged its way down Coldwater Creek. Despite the devastation—yards buried, bridges destroyed, water contaminated—no lives were lost. Thirty times the size of the Exxon-Valdez disaster, the Martin County spill generated little coverage in the national media.

Clinton administration officials in the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) took notice, however. MSHA head Davitt McAteer quickly dispatched a team of investigators, which included Spadaro, to determine the cause of the spill.

“He was real clear,” says Spadaro of McAteer. “I won't tell you exactly the language that he used, but he said, ‘Go down and find where we messed up so that it doesn't happen again.' So we started interviewing people and doing a drilling program that I was in charge of.”

The problem, the investigators soon learned, was that a similar accident had happened before—six years earlier—when 100 million gallons of slurry escaped from the same impoundment pond, owned by Martin County Coal, a subsidiary of Massey Energy. After that spill, Larry Wilson, a MSHA engineer, made nine recommendations that the company needed to implement before the pond could be used again. The recommendations were ignored; indeed, the coal company began filling the pond again on the same day as the spill. “That was the root cause of the accident” in 2000, Spadaro says.

But the incoming Bush administration wasn't interested in causes. Only hours after the new president's inauguration on January 20, 2001, Tony Oppegard, the head of the investigating team, learned that he had been fired. The remaining team members were soon told by David Lauriski, the new Assistant Secretary of Labor for Mine Safety and Health and director of MSHA, to conclude their work.

Spadaro was outraged. “We had more than forty other people we wanted to interview,” he recalls. These remaining interviews were expected to confirm what the team had already found: that Martin County Coal and Massey Energy knew that the impoundment was an accident waiting to happen, that they had willfully ignored MSHA's guidelines, that the trail of corporate corruption ran right down Pennsylvania Avenue.

The coal companies knew that they had a friend in George W. Bush. He had, after all, accepted hefty contributions from Massey Energy during his presidential campaign. And it didn't stop there.

“While they were being investigated,” says Spadaro, “Massey Energy made a contribution of $100,000 to Mitch McConnell,

who was the head of the National Republican Senatorial [Campaign] Committee. And of course, Mitch McConnell is very chummy with Don Blankenship, the head of Massey Energy, and McConnell is married to Elaine Chao, who's Secretary of Labor, who has jurisdiction over the Mine Safety and Health Administration.” Spadaro pauses, fixing a steady gaze on the blue West Virginia mountains just beyond the window.

“So they bought their protection,” he says.

They also scrubbed the final report of the investigation. Tim Thompson, whom Lauriski had named to take over the investigation, insured that the report would give Massey Energy a mere slap on the wrist. Initially, the investigators had recommended up to ten serious violations, some of them criminal. At Lauriski's direction, Thompson had those reduced to two minor infractions. Then, Thompson and Lauriski began pressuring Spadaro to sign the report.

At that point, Spadaro went public.

“I didn't hesitate at all,” he says. “I refused to sign the report. And from then on it was just one attack after another from Dave Lauriski and the people who worked for him.”

The retribution was swift. Spadaro was locked out of his office and placed on administrative leave from his position as superintendent at the Mine Safety and Health Academy in Beckley, West Virginia, near his home in Hamlin. After Lauriski's charges that Spadaro had abused his authority didn't hold up—the malfeasance amounted to Spadaro's giving free room and board to a field worker diagnosed with multiple sclerosis—Lauriski transferred Spadaro to Pittsburgh, more than 250 miles away from his family.

1

Spadaro filed an official complaint with the U.S. Office of Special Counsel in 2003, but he soon learned that the odds were stacked against him: this particular special counsel had found in favor of just one whistleblower. It was unlikely that he would be reinstated to his job at the academy. A deal was finally reached the following year: he would drop the charges in turn for being restored to his original pay grade. And he would retire.

“It was difficult for my family, difficult for my wife having all that public attention, having that conflict,” Spadaro recalls. “For me, I at least know that I did the right thing.”

The public thought so as well: “I had tremendous support from people in the mining communities, environmental groups, labor unions, all of that,” he says. “People demonstrated on my behalf in the streets of Charleston; they wrote letters; they raised hell about it.”

The public outcry was so scathing that the Department of Labor was forced to do an internal review of the Martin County investigation. Once again, it was a whitewash.

Spadaro sighs wearily, pausing to run his hand down his face. “One of Mitch McConnell's former staff members

2

was appointed to that investigating team so that Mitch had a direct line straight in to the investigation of that corruption that I had exposed. So he protected Massey Energy, and he protected the Department of Labor with that $100,000 that was contributed by Massey. There's no doubt in my mind.”

A ruling by a federal appeals judge further inflamed the situation. The final version of the report fined Massey Energy $55,000 for each of the two violations, but a subsequent court ruling lowered that fine to a mere $5,600.

One would think that after all this drama—the harassments, the threats, the lies—Spadaro might have lost faith in his government. To that, he replies with a quiet but emphatic “No, no.” His frustration, he explains, is more specific: “I had never seen such blatant, direct interference ever in government as what I saw with the Bush administration.”

It's not your typical partisan rant. Spadaro, after all, has worked under a total of eight administrations of both parties. He gives credit where it's due. In fact, Spadaro cut his investigative teeth during the Nixon administration in 1972 when he was studying another environmental disaster that occurred when a coal slurry impoundment dam burst at Buffalo Creek, West Virginia.

Spadaro was only twenty-three years old when the governor named him as staff engineer to the investigating team. Despite his years of experience working at the Bureau of Mines, he was anxious.

“I was just young and I'd been sent down to investigate this disaster,” he recalls. “I wasn't sure I knew enough to do any good.”

His support to both the investigation and the grieving community was immeasurable. Immediately, he set to work conducting interviews with the survivors. Their stories haunt him to this day.

“These were people who'd lost their loved ones, they'd lost their homes, they'd lost everything,” he says. “I'll never forget their voices.”

What Spadaro learned was horrifying: several government agencies were aware of the dam's instability. Each passed the buck to the other, assuming it would be repaired. To make matters worse, residents living downstream also knew the dam was dangerous. Many wrote letters to their government expressing these fears. “They just allowed the dams to exist,” Spadaro whispers.

Spadaro's experience in 1972 stayed with him. “The whole time, in all those years when I was working,” he says, “the Buffalo Creek disaster was my guiding light. I wanted to do whatever I could to make sure that that kind of thing didn't happen again.”

Spadaro lives by the adage that those who refuse to study the mistakes of the past are doomed to repeat them, which is why he found the Martin County spill in 2000 all the more sickening.

“We had a lot of support for Mine Safety and Health during the Clinton years,” he says. “We did not have it at all during the Bush years.”

Indignant, Spadaro leans forward in his chair and begins ticking off recent mining disasters on his fingers. “First, the Alabama disaster with the Jim Walters mine.

3

Then Quecreek.

4

Then the Sago disaster.

5

Then the Aracoma disaster and mine fire.

6

And then Darby in Harlan County.

7

And then Crandall Canyon in Utah.”

8

He throws his hands in the air. “Senator [Edward] Kennedy's committee

9

found out that there had been a plan submitted to MSHA by the coal company that was unsafe,” he says, referring to the tragedy at Crandall Canyon. “It was a roof control plan that was submitted and was unsafe. The district manager from MSHA overruled his own engineer and approved the plan, and within a month six people died in this tragic disaster.”

Leaning back, Spadaro shakes his head in disgust, trying to suppress his greatest fear—that another disaster could very well happen again. “I hope not,” he says.

Even in his retirement from MSHA, Spadaro is working to prevent other such tragedies. “My career's just a little different now,” he notes. “I'm not in government, but I'm still trying to do whatever I can to stop what's happening to people in the coalfields.”

Spadaro spends much of his time advising a variety of groups on subjects ranging from mine safety to labor issues to a ban on mountaintop removal mining: “I work with Kentuckians for the Commonwealth, the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition, Coal River Mountain Watch, the United Mine Workers a little bit, groups like the Anstead Historical Society in southern West Virginia—anybody who needs help that I think I can do some good with.”

The fight against mountaintop removal is the issue that has especially taken hold of his energies and expertise. Spadaro decries the devastation every chance he gets. “It's destroying a people, it's destroying the Mother Forest for North America, so it's morally wrong.”

Although he notes that there's enough blame to go around for the proliferation of the practice—he makes it a point to mention that mountaintop removal increased dramatically on Bill Clinton's watch—Spadaro harbors extra resentment toward the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), which his father and grandfather belonged to, and which he still occasionally works with on labor issues.