Something's Rising: Appalachians Fighting Mountaintop Removal (4 page)

Read Something's Rising: Appalachians Fighting Mountaintop Removal Online

Authors: Silas House and Jason Howard

Yet we have been changed for the positive, too. Working on this book has made each of us find his own way to be a better part of the solution. We're both convinced that leading a simpler lifestyle is beneficial not only for the environment but also for the soul. The people we've met and the stories we've heard have caused us to agree more than ever that standing up for what you believe in makes you and your country stronger.

We have been changed by listening to the stories of our people, and we will be haunted by them. We will not let them go unheard.

The rate at which mountains are being leveled increases every day. Dissenters are not asking that the coal industry be shut down; they are simply asking for mining to be done with respect and responsibility, treating the place and its people with dignity. So far the coal companies have refused to listen to that request. Government officials refuse to require them to do so. As in so

many other instances in history, our fate then lies within the hands of the people.

Thankfully, the people of Appalachia are rising up to make their voices heard.

In putting together this book we have spent many hours with each person we interviewed, observing them from afar before we ever approached them about being part of this project. After asking them if they would be willing to work with us, we then spent several hours interviewing them in their homes, on mountaintops, at local restaurants, on creek banks. More than one cooked us supper (proving the diversity of this region, we were offered everything from soup beans to homegrown strawberries to hummus). Some laughed to keep from crying. Others wept openly.

We want our readers to feel as though they have met these courageous people. We hope to accomplish that through the use of what we call the features that precede each oral history. In these introductory pieces, we present a feature-length story about the person, introducing him or her from our point of view before turning the book over to the subjects themselves, through their oral histories.

The people in this book are not only courageous fighters; they are also storytellers, poets, and stewards of the land. They are witnesses to a mining practice that is taking their place and tearing up their souls. Through talking about the environmental devastation that results from mountaintop removal, they have revealed the way their own culture, their heritage, their very memories are being scraped away, too. But their voices are rising, building in strength. They may now be only a murmur rolling over the mountains, but soon they will become a roar that will slide along the hollers and shady creeks, across ridgetops and cool cliff faces, until they are heard by everyone. These are their stories.

The Preservationist

I come from the mountains, Kentucky's my home

Where the wild deer and black bear so lately did roam

By cool rushin' waterfalls the wildflowers dream

and through every green valley there runs a clear stream

Now there's scenes of destruction on every hand

and there's only black waters run down through my land

Sad scenes of destruction on every hand

black waters, black waters run down through the land.

—Jean Ritchie, “Black Waters”

Jean Ritchie's eyes haven't changed since she was a young girl. At eighty-six years old, they are as blue as blown glass, full of wisdom and cleverness and intensity and, above all, kindness. Kindness lights up Ritchie's entire face, so clear and real that it causes her to seem almost not of this world. Beatific. And she possesses the same kindness in her hands, in the slight, humble bend of her neck, in her beaming smile. And of course that kindness is what comes through the clearest, the cleanest, in her voice. It is there in her speaking voice, but also in her singing voice, the quality that has caused the

New York Times

to proclaim her “a national treasure” and the reason Ritchie has become widely known as “the mother of folk.”

As soon as she enters the dining room of her home on the highest hill in Port Washington, New York, the natural illumination of her face is enhanced when she steps into the white light falling through the picture window over her dining table on this winter midday and she says, “Welcome, welcome,” in her gentle way.

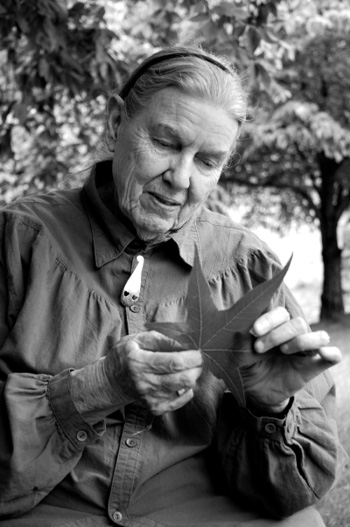

Jean Ritchie, Hindman, Kentucky. Photo by Silas House.

She pats her red hair, which she has just pulled up with a barrette on each side, her trademark part straight and exactly in the middle of her head. In that light, with a smile that covers first her mouth and then her entire face, for a split second she is a girl again. No matter all the knowledge those blue eyes hold: they must have been full of wisdom even then. For just a moment she is a child again, a girl frozen forever in time, the Singing Girl of the Cumberlands. Her eyes must have looked just this way at the age of twelve, as she described herself in her 1955 book,

Singing Family of the Cumberlands:

I watched the brightening sky and was proud that I could feel the frail beauty of it. I felt proud of my…lonesome feelings. I felt proud that I was who I was. I wondered if anyone would ever understand how much was in my mind and heart. I wondered if ever there'd come somebody who would know. You couldn't talk about such things. You had to talk about corn and dishes and brooms and meetings and lengths of cloth and lettuce beds. If you should start to talk about the other things—the things inside you—folks might think you were getting above your raising. Highfalutin. Maybe I was the only one. Maybe nobody else in this world felt the things I felt and thought the things I thought in my mind.

It wouldn't be long after having these thoughts that Ritchie would venture out into the world to find others like herself. But before that journey began, she learned nearly everything that would carry her through the rest of her life from her family and neighbors in the small community of Viper, in Perry County, Kentucky, where she was born in a cabin on the banks of Elk Branch in December 1922. Ritchie, the daughter of Abigail and Balis, was the youngest of fourteen, and a surprise to her mother, who was forty-four years old when Ritchie was born. “It's a mystery to me that the house don't fly all to pieces,” her mother used

to say, according to Ritchie. “I don't rightly know where they all get to of a night.”

Ritchie, as the title of her book suggests, grew up in a singing family, a family who would gather on the porch every evening to “sing up the moon.” They did everything together, singing all the while. “We'd sing while we worked and played, while we walked or did anything at all,” Ritchie says. “We'd sing in the cornfields or over the dishes while we washed them.” She can't remember anyone

not

singing. “We could all carry a tune,” she says. The songs they sang were all handed down to them from family members and dated back to long before their ancestors crossed the ocean. Today the Ritchie Family is best known for preserving the song “Far Nottamun Town.” In 1917 famed songcatcher Cecil Sharp found his way to the Ritchie Family and was sung to by Jean's older sisters Una and May.

When Ritchie was about four years old, she started eyeing her father's dulcimer, which he had bought for five dollars from a nearby dulcimer builder. No one in the family dared to touch it, knowing that it was Balis's prized possession, but often when he was in the fields, Ritchie says she would hide with it and play it. By the time she was seven, her father had caught on that she was sneaking around to play the dulcimer, but instead of punishing her, he sat down with her and began to show her a few things about playing the instrument. Over the next few years Ritchie taught herself to play. “I just watched him and did what he did,” she says. Her singing was heavily influenced by the high, clear voices of her mother and sisters. She says that most of the time they didn't use musical accompaniment. “Instruments were just so hard to come by back then,” she says.

An education was hard to come by, too, but Ritchie's parents—especially her father, a teacher—encouraged all of their children to graduate high school and to go on to college. “Dad wanted us to

all

go to school,” Ritchie says. “He'd talk about this and people would say, ‘Even the girls?' He believed in

all

of us.”

Two of Ritchie's sisters went to Wellesley by way of the Hindman

Settlement School,

1

but Ritchie didn't get the chance to board at Hindman since a new high school was built at Viper. She got a good education there, though, and went on to Cumberland College in Williamsburg, Kentucky, almost exactly 100 miles—and a world—away from home.

2

Ritchie then attended the University of Kentucky, where she received a degree in social work in 1946 (graduating with highest honors and a Phi Beta Kappa key). Immediately after receiving her degree, she moved to New York City, where she got a job at the Henry Street Settlement School on the Lower East Side, working with children.

3

“My plan was to go to New York and get some experience, then go back to the Hazard area to work,” she says.

“We had to find a way to entertain” the children, recalls Ritchie, “so I'd teach them Kentucky games, and they'd teach me Jewish games and games from Italy and Puerto Rico.” She also taught the children the songs she had grown up singing, accompanying herself on guitar and dulcimer. Students and coworkers alike became mesmerized when she sang. Before she knew it, and without even trying, Ritchie had acquired a following. She quickly became a popular guest at schools and parties throughout the city. At one of these gatherings she met George Pickow, an energetic magazine photographer who was making a name for himself with his pictures, which were a beautiful mix of reportage and art.

4

“I had heard there was this great singer that was going to be there, but I didn't care too much about what she was singing. I don't think I even listened, because she was so gorgeous,” Pickow recalls. Ritchie remembers that Pickow thought she was “putting on” her accent and that she wasn't “for real.” He soon found not only that she was very much for real, but also that he loved her way of singing. He quickly became her biggest fan, and remains so today.

One thing led to another, and eventually Ritchie found herself singing for Alan Lomax, the preeminent folklorist and musicologist who had fostered the careers of artists such as Woody Guthrie and Leadbelly. “Jean's quiet, serene, objective voice, the

truth of her pitch, the perfection and restraint of her decorations (the shakes and quavers that fall upon the melody to suit it to the poetry) all denote a superb mountain singer,” Lomax wrote in the 1965 preface to Ritchie's book

Folk Songs of the Southern Appalachians

.

In 1948 Lomax set up a concert for Ritchie at Columbia University. By 1952 she had a contract with Elektra Records and had released her first solo album,

Jean Ritchie Sings Traditional Songs of Her Kentucky Mountain Home

.

In 1950 she had eloped with Pickow, and they began what Ritchie calls “our folklore-collecting travels; myself as a singer/ dulcimer player/interviewer (gossip), and he as a photographer/ filmmaker/sound recorder.” Ritchie received a Fulbright Scholarship in 1952, and she and Pickow went to England, Scotland, and Ireland to “visit, swap music, tea-party and ceilidh with many wonderful folks,” she says.

5

The result was the 1954 album

Field Trip

, which contains traditional songs as sung by rural people in the countries Ritchie and Pickow visited as well as Ritchie's interpretations of her own family's variants of the same songs. This album single-handedly preserved an entire culture that might have been lost otherwise. In the original liner notes, Ritchie wrote of meeting the singers of the British Isles: “I had the warm feeling that I was back home in Kentucky, that these were my kinfolks, and I knew I had found what I had come searching for—I had found my roots, and the sources of my songs.”

On this trip she came into contact with a seventeen-year-old boy named Tommy Makem, who played tin-whistle but didn't know much traditional music. Makem went on to become one of Ireland's biggest recording artists (he is now known as “the Godfather of Irish Music”) and has credited Ritchie with inspiring his interest in traditional music. Thus, once again she had her hand in preservation, no matter how inadvertently.

In 1955, Oxford University Press published Ritchie's childhood autobiography,

Singing Family of the Cumberlands

, with illustrations by Maurice Sendak. The book has as much to do with

preserving traditional music as it does with preserving the storytelling tradition; in it, Ritchie examines forty-two of her family's most beloved songs. She had set out simply to save and explain her family's song variants, but she ended up writing a moving memoir of a time and place that was already forever gone. The book was published to wide acclaim, was excerpted in

Ladies Home Journal

, and is today considered a classic. It has never been out of print and regularly shows up on the syllabi of many Appalachian studies classes.

Ritchie went on to publish several songbooks that were interlaced with family and regional history. Three of them in particular—

Jean Ritchie's Swapping Song Book

(1952),

A Garland of Mountain Songs

(1953), and

Folk Songs of the Southern Appalachians

(1965) are indispensable texts for anyone interested in Appalachian music or culture. Together, they preserve more than 200 of the region's songs—some of which would have surely been lost otherwise. In all of them (but particularly in the

Swapping Song Book

) Pickow's accompanying photographs are themselves remarkable acts of preservation.

Ritchie became ever more active in the folk music scene and before long became one of the leading voices in the genre. Her involvement caused her to be incorrectly identified as a card-carrying Communist in a 1965 book called

Communism, Hypnotism, and the Beatles

, which named several singers as promoting Communism through their songs, and even earlier in small, now-defunct McCarthyite magazines.

6

Ritchie was shocked by the allegation, especially because of the way she found out about it. “I was performing at a college, sometime in the 1950s, I think,” recalls Ritchie. “After the program, a young girl pushed this little magazine at me and said, ‘Oh Jean—

why

did you ever become a Communist?' I assured her that I had never joined the Communist party. She showed me the magazine, and there I was, listed with other folksingers described as ‘Pete Seeger and his ilk,' who sang leftist songs on the streets. It went on to describe the songs as ‘leftwing' and ‘pornographic,' songs like ‘The Cherry-tree Carol.'

7

I

swear that this is the song they had picked to illustrate the terrible filthy things that we ‘Communists' were singing.”

By the end of the 1960s Ritchie had recorded twenty albums, served on the board of and appeared at the first Newport Folk Festival (where her iconic performance of “Amazing Grace” is still talked about by anyone who was there), and was considered one of the leaders in the folk music revival. She had also single-handedly popularized the mountain dulcimer. Countless dulcimer players have given Ritchie credit for bringing their attention to the instrument.

In 1974 she recorded what many consider the first of her three true masterpieces (along with

None but One

and

Mountain Born

) out of her forty albums.

Clear Waters Remembered

contains three of the original compositions she is most often recognized for: “West Virginia Mine Disaster,” “Blue Diamond Mines,” and “Black Waters.” It would also be the album that would solidify Ritchie's position as an environmentalist and activist.

“Black Waters” in particular became a rallying cry for the growing outrage against the environmental devastation being caused by strip-mining, which at the time was a fairly new method of mining coal. The practice was giving many Appalachians pause, especially because most of the coal companies were able to mine the coal with broad-form deeds, many of which had been sold decades before. Ritchie became a part of this movement with “Black Waters,” which became an anthem for the movement against the practice. After struggling over its creation, Ritchie finally finished the song after being invited to participate in a memorial concert for Woody Guthrie. She performed it for the first time during that show and introduced it as something Guthrie “might have written had he lived in Eastern Kentucky.” Besides being a powerful environmental song, it also resonated with Appalachians who might not have identified themselves as environmentalists but who had a love for the land in their blood.