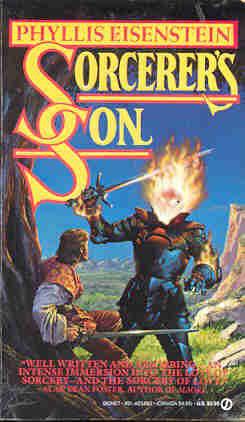

Sorcerer's Son

Sorcerers Son

Phyllis Eisenstein

The black knight slammed his shield against the sword in Cray’s left hand, and the blade shivered with the strength of the blow. Cray’s fingers, unused to curling about a pommel, went numb; he was barely able to hold onto the weapon.

Cray found himself backing off; suddenly his shoulders were against a tree trunk and he could not sidestep fast enough. The black knight came on. Cray raised his sword far to his right and then swept leftward with a blow too weak to dent plate armor, but strong enough and high enough to cleave a human skull. The steel bit deep into the black knight’s head.

In the instant that Cray expected to see bright blood gush from the sundered pate, the black knight burst into flame.

Cray screamed once and his sword arm fell to his side.

Fire engulfed him

––––––––––––––––––––––––––—

A Del Rey Book

Published by Ballantine Books

Copyright Š 1979 by Phyllis Eisenstein

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Ballantine Books of Canada, Ltd., Toronto, Canada.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 78-71231

ISBN 0-345-27642-6

Manufactured in the United States of America

First Edition: April 1979

Cover art by Darrell Sweet

––––––––––––––––––––––––––—

For Martha Eisenstein

with gratitude

for her love and encouragement

^ ť

Behind his walls of demon-polished bronze, behind his windows so closely shuttered with copper scales that no sunlight penetrated, Smada Rezhyk brooded over a leaf. It was a bit of ivy, small enough to fit within the palm of his hand, and written upon it in letters spun of gray spidersilk was the single word, No. A snake had deposited the leaf at the gate of Rezhyks castle, and he needed no signature upon the smooth green surface to tell him who had sent the message.

His footsteps rang against the floorstudded boots upon the mirror-bright metalas he strode to the workshop, to the brazier that had never cooled since the instant Castle Ringforge had been completed. His band passed above the flames, let go the leaf, which danced briefly in the upwelling heat until the fire caught it, curled it, shriveled it to ash. In the flickering light, the jewels upon his fingers sparkled, the plainer bands gleamed warm; each ring was a demon at his commanda demon of fire, a demon to build or destroy at his whim. He tallied them slowly, his only friends in the universe. Then he summoned one, the first and best of them all, faithful companion since his youth; the simplest ring, red gold, was inscribed with that demons secret name: Gildrum

From some other part of Ringforge, Gildrum came in human guise, entering by the door as a human would. In appearance, the demon was a fourteen-year-old girl, slight and pretty, with long blond braids. Rezhyk had given her that semblance when they were both young, and only he had changed with the passage of the years. He kept her near him most of the time and spoke his heart to her. She climbed atop a high stool by the brazier and waited for him to begin the conversation.

He was toying with glassware, with notebooks and pens and ink. He had not yet glanced up at her when he said, She refused me.

In a high, fluty voice, Gildrum said, Please accept my sympathy, lord.

She refused me, Gildrum! He turned to face the demon-girl, lines of anger set around his mouth. I made her an honorable offer!

You did, my lord.

Am I ugly? Are my manners churlish? Is my home unfit for such as she?

None of that, my lord.

What have I done, then? How have I offended her? When? Where?

My lord, said Gildrum, I do not profess to understand humans completely, but perhaps she is merely disinclined to marry anyone.

You are too soft, my Gildrum. He leaned on a stack of notebooks, forehead braced against his interlaced fingers. She hates me, I know it. It was a cold reply, brought by a cold creature. She meant to wound me.

And has succeeded.

For a moment only! Now I know my enemy. We must take precautions, my Gildrum, to make certain she never can wound me again.

The demon shrugged. Never again ask her to marry you.

Not enough! Who knows what evil she fancies I have done her? I must protect myself.

I would think you are well protected in Ringforge.

How? He clutched a length of his dark cape in both fists, I wear woven cloth; she could turn my very clothes against me.

Inside your own castle?

Am I never to set foot outside again, then? Must I wear plate armor every time I walk abroad? Or felted garments hung together with bolts and glue? She rules too much, her hand is everywhere. What can I do, Gildrum?

She smiled. A fire demon could keep you warm enough if your vanity would permit you to walk the world naked, my lord.

A sorcerer naked as a beggar? Hardly!

A beggar would not wear rings of power on all his fingers. People would know your rank.

Dont try my patience so, Gildrum.

Then I must think a moment, lord. Pursing her lips, crossing her arms over her bosom, she looked up at the ceiling. Just visible beneath the hem of her blue gown, her feet swung slow arcs between the legs of the stool, pendulums measuring the time of her thought. My lord, she said at last, if you are truly concerned about some danger from the lady, then I would advise you to construct a cloth-of-gold shirt, a fine mesh garment, supple enough to wear next to your skin. It must be made of virgin ring-metal, and you must draw and weave the strands yourself, without demonic help. Such a combination of your province and hers would be impervious to her spells and to any of your own that she might try to turn against you.

Rezhyk poked the coals in the brazier. A fine notion, Gildrum, but what is to keep her from discovering that the shirt is being made long before I finish it? I am no weaver, after all; it would be a slow process.

How will she discover it? You will do it here in Ringforge.

How does she discover anything? Every spider is her spy.

Even here in your own castle?

Even my own castle is not proof against vermin. They come and go as they please. He glanced about nervously. There are none here now, but they might get in at any time.

Well, then, you must do something about them. Post a watch of fire demons to burn every spider that approaches the outer wall.

She will take that as an affront!

Gildrum sighed. Worse and worse. Perhaps if you just sent her a vase of flowers and begged her forgiveness

?

Rezhyk paced a slow circle about the brazier. If only we could arrange for her to take a long sea voyage, or to go into seclusion in some distant cave for a while. How much time do you think the making of the shirt would require?

As you said, you are no weaver. Perhaps a month. Perhaps two. No more than that, I think, if I show you exactly what to do. She held up a hand to stop his pacing. There is a way to weaken her powers for a month or two, my lord.

Yes?

If she conceived a child, the childs aura would interfere with her own. She would be limited, severely limited.

Enough

?

Enough that she could hardly speak to a creature beyond her own castle walls.

Rezhyk shook his head. She would abort the child. She would abort it as soon as she realized it existed. She could not allow that kind of vulnerability.

A month or two, I said, my lord. Until she noticed the pregnancy. Until she noticed the curtailing of her powers.

She might notice immediately.

Gildrum spread her hands, palms upward. I have no other suggestions.

We would have to work quickly. A month is too long. Could I do it in a week?

Working night and day, my lord, working with perfect efficiency, you might possibly do it in a week. At the end, you would be exhausted.

I have no choice. He opened the drawer where he kept his stock of ring-metal. Gold lay within, and silver, copper, ironwooden boxes held chips and chunks of each, surplus from old rings, and a few small ingots. I have a gold bar, never used. Will that be enough?

Yes.

He hefted the bar in one hand. This will be a heavy garment.

You will grow strong wearing it.

He set the metal on his workbench. We have only one problem, my Gildrum. He glanced up at her. How to bring about this pregnancy.

Gildrum smiled. Leave that to me.

Rezhyks gaze traveled the length of the demons girl-body. You suit me well, but for her

for her we must give you another form.

Tall, said Gildrum. Tall and lean and just past the first flush of youth.

Rezhyk worked two days and two nights to model Gildrums new form in terra-cotta. Life-sized he made it, strong of arm and broad of shoulder, sinewy and lithe, the essence of young manhood. Other sorcerers, when they gave their servants palpable forms, made monsters, misshapen either by device or through lack of skill, but Rezhyk molded his to look as if they had been born of human women. Complete, the figure seemed almost to breathe in the flickering light of the brazier.

Satisfied with his work, Rezhyk set his seal upon it: an arm ring clasped above the left elbow, a band of plain red gold, twin to the one he wore on his finger, incised with Gildrums name. Gently, but with a strength that would seem uncanny in so slight a body, were it truly human, Gildrum lifted the new-made figure in her arms and carried it across the workshop to a large kiln whose top and front stood open. She set the clay statue inside, upon a coarse grate.

Rezhyk nodded. Enter now, my Gildrum.

The demon-as-girl smiled once at her lords handiwork, and then she burst into flame, her body consumed in an instant, leaving only the flames themselves to dance in a wild torrent of light. Billowing, the fire rose toward the high ceiling, poised above the kiln and, like molten metal pouring into a mold, sank into the terra-cotta figure and disappeared. The clay glowed red and redder, then yellow, then white-hot

Rezhyk turned away from the heat; by the light of the figure itself he entered its existence, the hour, and the date in the notebook marked with Gildrums name. By the time he looked back, the clay was cooling rapidly. When it reached the color of ruddy human flesh, a dim glow compared to the yellow of the brazier, if began to crumble. First from the head, and then from every part, fine powder sifted, falling through the grate at its feet to form a mound in the bottom of the kiln. Yet the figure remained, though after some minutes every ounce of terra-cotta had been shedthe figure that was the demon, molded within the clay, remained, translucent now, still glowing faintly from the heat of its birth. The ring that had been set upon the clay now clasped the arm of the demon, its entire circle visible through the ghostly flesh. Then the last vestige of internal radiance faded, the form solidified, and the man that was Gildrum stepped forth from the kiln.

He stretched his new muscles, ran his fingers through his newly dark hair. As always, my lord, he said in a clear tenor voice, you have done well.

I hope she thinks as much. He slipped the ring from Gildrums arm and tossed it into the drawer from which he had taken the gold bar. There must be nothing that smells of magic about youabove all, nothing to link you with me.

Gildrum nodded. I shall steal human trappings, I know of a good source.

You must not fail.

Have I ever failed you, lord?

No, my Gildrum. Not yet.

And not now. His form wavered, shrank, altered to that of the fourteen-year-old girl, naked in the light of the brazier. Will you give me the seed for the child, my lord? Or must I find some beggar on the road?

He took her hand. Ill give it.

Rain poured down upon the forest from clouds crowded close above the treetops. On the muddy track below, a large black horse, tail and mane matted with wet and filth, trudged toward the nearest sign of life, a high-spired castle overgrown with ivy. The horses rider slumped forward over the pommel of the saddle, one arm hanging limp on either side of his steeds drooping neck. He was dressed in chain mail, a mud-spattered surcoat plastered atop the links; he had no helm, and his shield hung by a loose strap, bouncing against his leg in the slow rhythm of the horses walk. On his left side, where the surcoat was ripped and the chain snapped to make a hole a hand-span wide, blood seeped out sluggishly, easing down his thigh in a rain-diluted wash.

As they neared the castle, the horse picked up its pace, sensing the shelter ahead. The storm drove from beyond the fortress, and so there was respite from both wind and wet in its lee. Almost at the arch of the gate, the animal stopped and bent to drink from a puddle and to crop a bit of soaked grass; its rider fell then, slid silently off its back and dropped to the mud in an awkward heap.