Soulstealers: The Chinese Sorcery Scare of 1768 (30 page)

Read Soulstealers: The Chinese Sorcery Scare of 1768 Online

Authors: Philip A. Kuhn

An opportunity now presented itself to the grand councillors:

Grand Secretary Liu T'ung-hsun was about to depart Peking for the

summer capital. At sixty-eight, Liu had a distinguished record in the

upper reaches of Peking politics (including twelve years on the Grand

Council) and a reputation as an incorruptible official, an outspoken

breaker of bad news, and an advocate of unpalatable policies. Though

Hungli may sometimes have considered him meddlesome, he bore

Liu an unshakable respect. He had once briefly imprisoned Liu for

an unwelcome suggestion, but shortly pardoned him and continued

to employ him in the highest positions, including that of chief tutor

of the emperor's sons. So deeply did Hungli appreciate his toughminded servant that upon Liu's death in 1773 he paid a personal

condolence call upon his family.27 As senior grand councillor on the

scene, Liu had sweated through the Peking summer while the sovereign was at Ch'eng-te. As sorcery fear gripped the capital, he had

handled the delicate job of unearthing the culprits while not raising

panic among the common people. As soulstealing culprits were

shipped in from provincial courtrooms, he had ample exposure to

the shoddy and mendacious cases prepared by local prosecutors. His

memoranda to Hungli are masterpieces of subtlety: they lay out the

defects of the cases, including long quotes or paraphrases of the

recantations, all carefully packaged in a (logged zealotry that refuses

to accept the "crafty" and "evasive" testimony at face value. These

documents, at least, could never expose Liu to charges of being soft

on soulstealing. After the singing beggar recanted in Peking on

October 15, it was time something was done to spare the Throne

worse embarrassment. This would require concerted action in the

monarch's presence.

As president of the Board of Punishments, Liu had the annual

duty of journeying to Ch'eng-te to help the monarch scrutinize the reports of the autumn assizes, in which condemned prisoners' cases

were reviewed. When the reviews had been presented to the Throne,

Hungli would check off (kou-tao) those to be put to death. The routine

every year was for Liu, who had remained in Peking to manage

Grand Council business, to journey to the summer capital around

the middle of October and accompany His Majesty back to Peking.

On the leisurely southwest progress through the crisp autumn countryside, Hungli, in consultation with Liu, would brush a vermilion

"check" next to each condemned name.28 Liu left Peking on about

October i8 and was in Ch'eng-te by October 21. He and Fuheng

were with the monarch for the next five days.

A meeting of minds must have occurred by October 25, to judge

by the tone of Duke Fuheng's subsequent interrogation reports. Gone

now was the hedging about miscarriages of justice, gone the apparent

reluctance to accept recantations at face value. Liu joined the procession when the court set out upon the road on October 26, while

Fuheng remained in Ch'eng-te to finish interrogating the prisoners.

The imperial party reached Peking on November i, and two days

later Hungli called off the soulstealing prosecution.29

Calling off the campaign was not a simple matter of canceling

orders. The Throne had invested in it se, much prestige and moral

authority that a more ceremonious ending was required. i0 First, court

letters were sent by Fuheng, Yenjisan, and Liu T'ung-hsun to all

governors-general and governors. The queue-clipping case had

"spread to various provinces" because officials in Kiangsu and Chekiang had not reported it promptly. The response to repeated imperial

edicts had been maladministration by "local officials." As a result,

those cases that were brought to trial "were not without incidents of

extortion by torture." (This last, added to the court letter in vermilion, clearly troubled Hungli, though he certainly had known about

it earlier in the campaign.) Therefore he had ordered criminals sent

to Peking for reinterrogation. None turned out to be the chief criminals, and there were many instances in which innocent persons had

been falsely accused. This was "all the result of local officials in

Kiangsu and Chekiang letting the affair fester to the point of

disaster." Any further prosecution would simply disrupt local society.

This would be "inconsistent with our system of government." The

prosecution was therefore to be stopped.

Curiously, however, the court letter insisted that this should not be taken by local officials as a signal to relax vigilance. Watchfulness was

still the order of the day, and an official who captured a "chief

criminal" would thereby be deemed to have "redeemed his faults. 1131

On the same day was promulgated an open edict that cast all the

blame on provincial officials. The soulstealing menace, it began, first

appeared in Kiangsu and Chekiang, then spread to Shantung and

other provinces. Had provincial officials rigorously prosecuted the

case "when they first heard of it," pressing their local subordinates

for results, "clues could naturally have been found, and the chief

criminals would have been unable to slip through the net." Instead,

"right from the beginning" bureaucrats had followed their accustomed routines and failed to report the matter, "seeking to turn

something into nothing," and only when pressed by the Throne itself

did they begin to order prosecution.

Now, although there have been arrests in Shantung, Anhwei,

Kiangsu, and Chekiang, "We feared that among them there were

some whose depositions were extorted by torture." Therefore Hungli

had ordered that the criminals be sent to Peking for interrogation

by a tribunal drawn from the Grand Council, the Board of Punishments, and the Peking Gendarmerie. The original depositions proved

unreliable, and there were indeed cases of extortion by torture. "It

was apparent that in those provinces officials began by concealing

the facts and followed by evading responsibility." As a result, the

"principal criminals" were not caught. Nothing was done but to "send

petty functionaries out in all directions to cause trouble for the villages." This was "entirely out of keeping with our system of government." Here Hungli bit the bullet: "Now, at last, it will not be necessary to continue prosecuting this case."

How are we to reconcile the ambivalence of the secret court letters

and the vindictiveness of the open edict? It is plain (from the vermilion emendation) that Hungli was personally upset and embarrassed by the confessions concocted under torture. Yet the fact that

he continued to insist (in the secret channel) on vigilance, and (in

both channels) on the objective existence of the "chief criminals" even

though not a single one had been found, suggests a face-saving

compromise. Hungli's state of mind emerges most lucidly in an

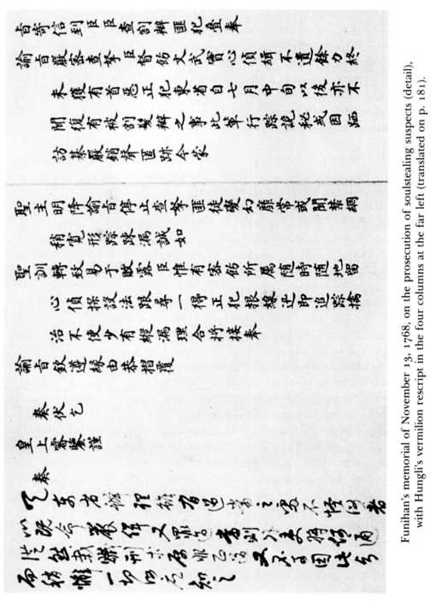

extraordinary vermilion rescript to a memorial from Funihan. The

Shantung governor had replied to the November 3 court letter in

plaintive terms. He had prosecuted the case "with dedication" and had "spared no effort." Although the chief criminals had not been

caught, "Shantung was then free of queue-clipping incidents after

mid-August." The vermilion reads:

Seen. Although Shantung's handling of this case did exceed the bounds

of propriety, We shall not blame you. If you were held responsible for

excesses after being ordered to prosecute rigorously, then how would

provincial officials know, in the future, what course to follow? Nevertheless, planting evidence and seeking-by-torture are really not the Correct Way.3°

Let such candor not tempt the governor into "negligence," warned

Hungli. Yet a whiff of royal remorse was in the air, and provincial

officials were exceedingly sensitive to the prevailing winds. Hungli

knew that the dignity of the Throne could be maintained only by

insisting on the reality of the plot and by punishing officials who had

failed to prosecute with sufficient vigor. The other side of the compromise, however, was to impeach officials who had tortured false

confessions out of innocent people.

Settling Accounts with the Bureaucracy

So far, there had been no concession that the case itself was poorly

founded. On the contrary, the chief "criminals" had really existed

and had eluded justice because of provincial mismanagement. Punishment was now in order: "Those governors-general and governors

of Kiangsu and Chekiang, who let this case fester to the point of

disaster," were to be referred to the Board of Civil Office for "rigorous discipline," in order to "rectify the bureaucratic system.":;; Here

was Hungli's revenge for the cover-up. Those to be disciplined for

laxity and mendacity were Governor-general G'aojin (Liangkiang),

Governor] an gboo (Kiangsu), Governor Feng Ch'ien (Anhwei), Governor Hsiang Hsueh-p'eng (Chekiang), Governor Yungde (Chekiang), Governor Mingde (Yunnan, formerly Kiangsu), and Governor Surde (Shansi). A number of county-level officials were cashiered for having exonerated sorcery suspects the preceding spring.

To keep the compromise in balance, a number of lower officials were

impeached for manufacturing evidence through the improper use of

torture on innocent prisoners. Some distinguished careers were

ruined, particularly among lower officials. Prefect Shao Ta-yeh of

Hsu-chou, for instance, was a renowned administrator whose flood control work had spared his people from inundation over a tenure

of seven years. In retribution for his part in botching the case of the

singing beggar, he was rusticated to a remote military post, where he

died a few years later.34

The nub of the problem, however, was Governor Funihan himself,

whose memorials (and enclosed confessions) had kept the soulstealing

case on the boil for three months. Day after day, the grand councillors

at the summer capital and at Peking had viewed the human debris

sent up from Shantung courts as they reinterrogated the soulstealing

criminals. Governor Funihan had insisted all along that his own

interrogations "did not rely upon torture," a statement that had

greatly enhanced the credibility of the confessions.35 What, then,

asked the grand councillors, was the meaning of these gravely

wounded prisoners, whose lacerated bodies still had not healed?

Monk T'ung-kao, should he survive, would be maimed for life. If

they had been tortured in county or prefectural courts, had not

Funihan seen their condition personally when they were brought

before him? Funihan was ordered to explain himself.36

The governor replied that, when he first saw beggars Ts'ai and

Chin, it was evident that they had been tortured, but "they could still

walk," and had named their masters and confederates without undergoing further ordeals. As for the crippled T'ung-kao, he had only

appeared at the governor's court after the dispatch of the "no torture"

memorial. Funihan then humbly reminded His Majesty of his own

command of August 5 to "do your utmost" (chin fa) to dig the truth

out of the culprits. With that sort of backing, he asked, why would

he have hesitated to report that "conscientious investigating officials

had used torture" in pursuing the case? At this rather spunky

rejoinder came the vermilion sneer: "Even more mendacious." The

Board of Civil Office was ordered to recommend punishment.37

When it came, the punishment was rather mild, considering how

much trouble the governor had inflicted upon the bureaucracy, and

embarrassment upon the Throne. The offense, of course, was not

torturing prisoners (Hungli had already expressed a certain sympathetic understanding on that point), but lying about it to the Throne.

Funihan was demoted to the post of provincial treasurer of Shansi

(Vermilion: "and take away his rank while in the job") but was perhaps relieved that Hungli forbore to route the case into the criminal

track, as he had for his predecessor Governor Chun-t'ai sixteen years earlier in a roughly similar context. In the light of all that had

happened, Funihan had received but a slap on the wrist: an unmistakable concession of royal error .38

The End of the Trail

Once the monarch was firmly oriented toward calling off the prosecution, the inquisitors knew that it was all right to resolve these

embarrassing cases. Exonerations followed quickly and clearly. First

resolved were the cases of the monks who were nearly lynched at

Hsu-k'ou-chen and the beggars of Soochow. On November 8, Fuheng

confirmed the original finding of the Wu County magistrate: Chingchuang and his companions were all "honest monks true to their

calling" and should be released forthwith. Fisherman Chang, who

had accosted them in the temple and pursued them into the street,

was to be held responsible for the disturbance. Although they were

unable to prove that this was an attempt at extortion (like that of

constable Ts'ai in Hsiao-shan), the grand councillors decided that a

beating was not enough for fisherman Chang. Besides being required

to make restitution to the monks for their lost baggage and money,

he was to be exposed in the cangue for two months "to instruct the

people." The ruffians who had robbed their boat, Li San and T'ang

Hua, were each to be beaten eighty strokes according to the useful

statute that forbade "doing what ought not be done."39