Southern Gods (7 page)

Authors: John Hornor Jacobs

Sarah bowed her head like a child. She pressed her cheek to her mother’s breast, found bone where she had once found soft flesh, and wept. Her mother shushed her and brushed her hair. “Sssh, baby. It’s gonna be okay, we’re gonna be all right. Everything’s gonna be all right now that we’re together.”

Sarah cried into her mother’s breast, hoping with all her heart it was true.

Chapter 4

T

he morning after the Meerchamp collection, Ingram called Ruth Freeman on the kitchen phone. She sounded happy, eager even, to see him as soon as possible. She gave him directions to their bungalow on Bellevue, off Poplar. An infant squealed in the background.

Maggie, bustling about in the kitchen, smiled at Ingram. He placed the phone’s receiver on the cradle.

“You been busy, I see. Hope you found your room to your liking. Must’ve come in late; I didn’t hear you come in last night.”

Ingram smiled back, resting his haunches on the counter near the phone.

“I got in pretty late. Usual. Had a job to do, and it took a while to get paid.”

“Well, long as you got paid. That’s all that matters, don’t it?” Maggie’s smile grew larger, and she gave Ingram a wink as she wiped an invisible speck from the center isle of the kitchen. “Coffee?”

“That’d be great, Maggie. Oh, that reminds me. Here’s next week’s money for… well… for our arrangement.” Ingram withdrew his wallet and gave Maggie a five dollar bill. “I got a job that’s gonna take me out of town.”

“That’s good you got more work. Where you going?”

“Believe it or not, to Arkansas. Drove through there once on the way to California. Can’t remember it much.”

“Well, there’s not much to remember about Arkansas, if you’re lucky.”

“No, I guess not.”

Maggie stopped wiping the counter, opened a cabinet, and removed a coffee cup. “Milk and sugar?” She lifted her head. Ingram nodded. She continued, “I’m from Arkansas, Bull. Can you believe that? Born and raised there.”

“Really?”

“Yessir. Now, a lotta folk think Arkansas is the most backward state known to mankind, and that’d be true, if it wasn’t for Mississippi.” Maggie leaned her head back and laughed at her own joke. Her teeth shone white against the darkness of her skin. Ingram frowned. “I came here to look after an aunty and never left. But I want you to look after yourself over there. It’s a whole different place. People think different, act different. There’s deep places in the earth over there, places that man knows only a little, deep tracks of forest that no white nor black man has walked on still since the Indians held the land. Someone who doesn’t know their way can get lost real easy.”

“Deep places in the—”

She waved her hand dismissively. “You get into any trouble, I want you to try and find Gethsemane, that’s the town I come from. My daughter, Alice, she still lives there and can help you if you need it. I’ll send her a letter and tell her you might be through that way.”

“Maggie, I’m only going to be over there about a week, at most. No need to do any of that, I’ll just—”

“Bull, I’m trying to tell you something. Over there, in Arkansas, things don’t go the same way they go everywhere else. Things take longer, things go wrong. Roads are bad, bridges go out. It’s backward, Bull. But it’s got its strong points too.”

“Like what?”

“Well, it’s a garden, really. The soil is rich and red like blood, or brown like chocolate, least where I come from. Things take root and grow real easy, game gets fat off the land, and sometimes, it seems like all a man or woman has to do is stretch out her hand, God’s bounty is there for the taking. I guess I ain’t making much sense, but it’s important you watch yourself. People think that place is just a bunch of hicks, and yes, that’s what they are, but they’re more than that too. Just stick to the villages and towns, stay away from the little places away from the main roads and cities. Stay in the lighted areas.”

Ingram grinned. “You’d think I was going into Transylvania or something from the way you talk, Maggie.”

Maggie handed Bull his coffee, and said, “There’s worse things than getting bit on the neck. Come on, I’ll help you get packed. I did some of your laundry last night while you was out carousing, should be dry by now.”

***

Early and Ruth Freeman kept a tidy little cottage on Bellevue Avenue, nestled in a copse of oak and birch trees.

Ingram pulled the coupe into the drive. A small, tawny woman came out on the house’s front porch at the sound of Ingram’s car. She was slight, high breasted, and modestly dressed in a maroon skirt and white blouse.

As he walked toward the house from the coupe, she began to appear older, lines of worry and stress stenciling their way into her skin. Her eyes were puffy and red. She wrung her hands as he approached.

“Mr. Ingram?”

“Yes, ma’am. That’s me.”

“Tell me it’s true, you’re gonna find my Early.”

Ingram took off his hat and stopped. “Well, I’m gonna do my best. That’s why Mr. Phelps sent me over here. Maybe we should go inside and talk about it.”

Inside, Ruth poured Ingram a glass of sweet tea, two ice cubes. Yellow flowers decorated the sides of the glass. An infant babbled in another room. Ruth glanced toward the back bedroom, and said, “Supposed to be nap time, but the little tiger doesn’t know what’s good for him.”

Ingram sipped his tea. “Mm. That’s good tea, ma’am.”

She twisted a dishrag in her hands. “Please tell me what you’re gonna do to find my Early.

Please

.” Her eyes welled with tears.

Ingram had no true experience with weeping women. The only time he’d seen his mother cry was on his seventeenth birthday, when he’d boarded the train that took him to Tuscaloosa and basic training. He’d been packing his duffel bag and his mother appeared at his bedroom door, apron white in the light from the window. She embraced him, grabbing him fiercely like she’d had when he was a little boy, when it was easier to wrap her arms around him. She stood back, her hands on his biceps, and looked up at him, staring hard into his face. “You’ll be careful, won’t you?” Tears came to her eyes, and she wiped them with her apron. By ’45 when the war was over, she’d died of cancer, and he still lived when, over and over in the Pacific, he thought the opposite would surely be true.

Ingram said, “I’m gonna try and pick up his trail in Brinkley, ma’am. Maybe he just got sick and holed up in a hotel until it passed over.”

Ruth shook her head. “For ten days? No. But maybe he’s been tossed in jail. Early drinks sometimes to sickness. Or maybe he’s shacked up with some woman… and you know… that’s fine if he is. At this point I’d rather him be doing that than… well—”

She didn’t want to be a widow just yet, and he couldn’t blame her.

“Ma’am,” Ingram began again, as gently as he knew how, “I came over here to see if you could tell me anything about his last phone call, what he might’ve said or mentioned.”

She sniffed and wiped her eyes. “Well, he didn’t say much, just told me he loved me and for me to kiss little Billy for him. He said he’d stayed in England and Stuttgart and laughed, saying all he needed now was to stay in Paris and London. Oh. He did say one more thing, said he had heard about a blues man Mr. Phelps might be interested in and was gonna try to see the man play at a roadhouse, but he didn’t say where.”

“Did he mention the blues man’s name? Was it Ramblin’ John Hastur?”

Ruth paused, looking uncertain. “Could’ve been. I’m sorry, Mr. Ingram, I can’t remember. Right about then little Billy started crying.”

“That’s okay. So let me get this straight.” He cleared his throat. “Early had been to England and Stuttgart the day or night before his call. That’s good to know.” Ingram grabbed his hat off the kitchen table and moved back toward the door. “I’ll do my best to find him, ma’am. Shouldn’t be no problem.”

Ruth began crying then for real, not just sniffles and welling tears. A flush came to her face, her eyes hitched up in pain, and she moaned. A soft blubbery sound. Tears poured down her cheeks, her mouth pulled down at the corners into a grimace.

“Please find him. He’s all we got,” she wailed, and she threw herself against Ingram’s chest.

Ingram felt her body pressed against his, her breasts pushing into his stomach, and wondered if she’d already begun planning for her husband’s demise.

On the way out of town, Ingram stopped, filled his tank, and bought a map of Arkansas. As he paid, the clerk at the counter said, “Going hunting?”

“Maybe. Why’d you ask?”

“Only couple of things to go to Arkansas for. One’s hunting and t’other’s fishing. That’s all.”

“Well, then, I guess I’m going hunting.”

The man behind the counter handed Ingram his map. “Good luck.”

Flipping the brim of his hat, Ingram said, “Thanks. Looks like I’ll need it.”

***

Ingram drove west on Highway 70 into Arkansas. Crossing the Mississippi, its turgid brown waters taking their swift, inevitable course south past Helena, past Greenville, even further south into the Louisiana swamps and tributaries, the French parishes, Ingram felt connected to something larger than himself. The slats of the wooden trestle-bridge rattled and clattered as he drove the coupe over them, his window down, the smoke from his cigarette whisking out into the freshening afternoon air, the slanting rays of the afternoon sun dappling the highway. The trees stood dark at the roadside in the afternoon light, but Ingram made out oak and cypress, bone-white birch, each one slowly passing. Particles of cottonwood hung suspended in the air, rising and falling, flashing by Ingram’s open window. He smoked and drove west in the gathering gloom of the dying afternoon, the greens becoming black.

The deep forest and swamps lining the Mississippi broke and leveled into flatter landscape. Fields and farmhouses slowly drew by his windows. The tires of the coupe thumped on the brown concrete slabs of the highway, each section’s tar seam thudding and rocking the coupe on its shocks. Outside his window furrowed fields rolled past, the rows of beans and cotton passing like spokes of an enormous wheel, its hub far off past the horizon, the rim meeting the road.

He passed through small towns, buildings clustered around a railroad or a granary. Not much traffic on the highway, very few people in the fields barring an occasional lone tractor turning over the earth, a combine trundling across a dusty plot, a battered and beaten truck rolling down a gravel road, throwing dust against the sky. The country seemed nearly abandoned, as if all the people had been spirited away and left their homes and fields to turn to dust.

Ingram flipped on the radio and scanned the AM band, rolling the knob slowly from left to right and then back, searching for signals. Hisses and pops, signal squelches, then the infrequent clear reception of broadcast filled the car and whisked out the window like Ingram’s cigarette smoke. Each station crackled like a procession of avaricious ghosts; pastors fervently preaching, adverts and jingles hawking soap and dishwashing detergents, plaintive country music, the drone of news.

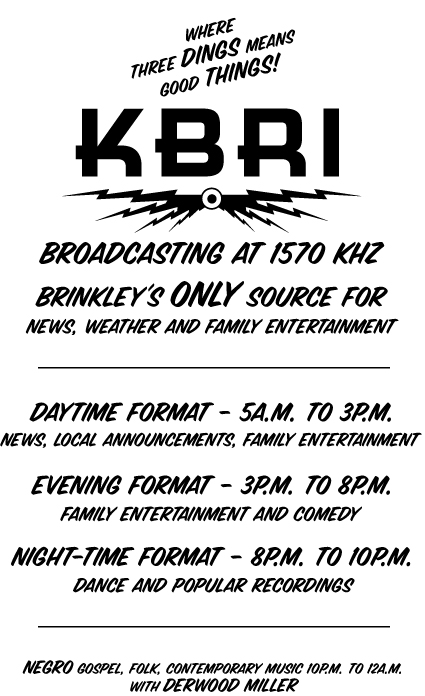

He dialed in 1570, the frequency Phelps indicated was Mr. Couch’s station. At first that frequency was just static, the occasional word rising through the noise like a fish rising to the surface of a murky pond, pale and indistinct. Closer to Brinkley, the signal gained clarity, coalescing into something understandable.

KBRI played swing and big band platters, Lawrence Welk, Jimmy Dorsey, Johnny Mercer, and Vaughn Monroe—Ingram thought of this music as the drone of the USO.

The more Ingram listened, the more he thought of the music at Helios Studios. Rhythm and blues, Phelps had called it. A driving beat married to raw emotion that Ingram found the big band music lacked. And then Ingram remembered Hastur and the “Long Black Veil.” The chanting and sound of slaves marching, the sound of knives and pain and hatred.

Despite the heat of afternoon, Ingram shivered. He switched off the radio and drove in silence.

The coupe devoured the miles. Before dark, Ingram rolled into Brinkley, a hundred miles west of Memphis. Driving down the main drag, Ingram scanned the buildings looking for the KBRI call signs. He spotted them near a nexus of power lines and transformers running into a short narrow building with a large plate glass window. The door read:

Behind the building was a steel tower stabbing into blue sky.

Ingram pulled the coupe into a diagonal parking space, put on his hat, and went inside.