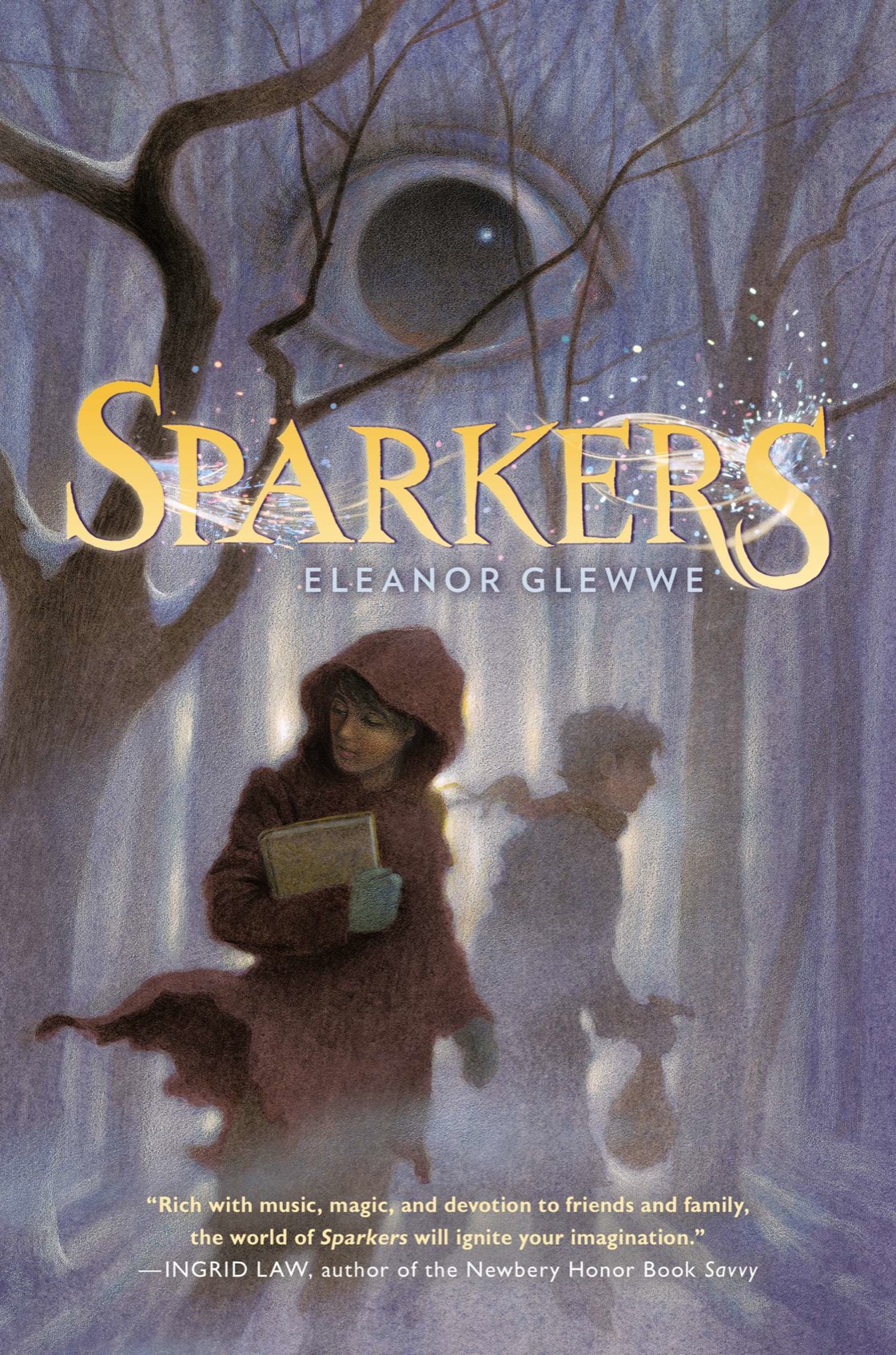

Sparkers

Authors: Eleanor Glewwe

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA / Canada / UK / Ireland / Australia / New Zealand / India / South Africa / China

A Penguin Random House Company

First published in the United States of America by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Young Readers Group, 2014

Copyright © 2014 by Eleanor Glewwe

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

LIBRARY

OF

CONGRESS

CATALOGIN

G

-

IN

-

PUBLICATION

DAT

A

Glewwe, Eleanor.

Sparkers / Eleanor Glewwe.

pages cm

Summary: “Marah, an underclass âsparker' in a society ruled by magicians, works with her friend Azariah to find a cure for a mysterious disease that turns its victims' eyes black”âProvided by publisher.

ISBN 978-0-698-15083-6

[1. Fantasy. 2. Social classesâFiction. 3. MagicâFiction. 4. DiseasesâFiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.G48837Sp 2014

[Fic]âdc23

2013038475

Version_1

To my parents, Mary Yee and Paul Glewwe

Prologue

PrologueT

he first time I went to the Ikhad by myself, I was eight years old, and my father had just died.

The Ikhad, the biggest marketplace in Ashara, hummed with activity. Around the edge of the vast, cobbled square, shopkeepers arranged their wares on rickety tables outside their stores. Young men trundled in and out of side streets, pushing carts piled high with sacks of flour or coal. Children dashed past me cradling paper cones brimming with spiced nuts.

The jangling of the coins Mother had given me made me nervous. I was afraid they would fall out of my pocket. But this was my first solo errand, and I was determined to carry it out.

The thatched roof of the Ikhad floated above me on spindly wooden posts. A river of shoppers swirled between the stalls. I slipped into the current and had soon purchased a cabbage, a bunch of carrots, and some chard. Feeling proud, I was on my way out of the Ikhad when I noticed a pair of kasiri stalking through the crowd, silver police badges gleaming on their black uniforms.

I froze, terrified they might shoot sparks of magic my way. Innocent or not, all halani knew better than to catch the attention of the police. Once they had passed, I ran in the opposite direction until I found myself in an unfamiliar corner of the Ikhad. I stopped to catch my breath.

On the stall before me rose a mountain of books. I felt a pang; Father had been a lover of books. He had taught me to read when I was small, and on the weekends, he would take me exploring in bookstores in halan neighborhoods. We could rarely afford to buy anything, even though by halan standards he'd had a good job. He'd been the foreman in charge of the blast furnaces at one of Ashara's steelworks.

Now, at the Ikhad, I hugged the cabbage to my chest, grief squeezing my heart. Three weeks earlier, there had been an explosion.

As I stood in front of the teetering piles of books, an old woman peered around one of the stacks. She was small and bony, dressed in layer upon layer of faded clothing. Wisps of white hair drifted out from under her knit cap. Her eyes were light in a wrinkled face browned by the sun.

“Who might you be, little one?” she said.

“My name's Marah,” I whispered.

“I'm called Tsipporah,” she said. “What sort of books do you like, Marah?”

I was too shy to answer.

From the jumbled stacks, the bookseller picked out a volume bound in dove-gray cloth. It was filled with stories. Turning the pages, I discovered woodcut illustrations of a sparkling pool, a mountain valley, and a caravan snaking across sand dunes. Cabbage, carrots, and chard were forgotten, along with Mother and Caleb, my little brother, waiting for me at home.

The old woman handed me another book, and I skimmed the table of contents. To my delight, it was sprinkled with the names of faraway lands like Xana and Aevlia. Tsipporah selected still more books for me, somehow knowing which ones I would like.

Glancing down at a thick tome on which I had set the cabbage, I noticed an unfamiliar script on the spine. I touched the flaking gold letters. “What's this?”

“Ah,” said Tsipporah, pleased. “That's Old Monarchic, the language of scholars in the days of Erezai. You know about the kingdom of Erezai?”

I had heard the name once or twice, but we hadn't yet learned about Erezai at school, so I shook my head.

“Shall I tell you a story?” the old bookseller asked.

I smiled. “Yes, please.”

“Well,” she said, “five hundred years ago, before the city of Ashara was a sovereign state, all the north lands were one country: the kingdom of Erezai. It was a land thick with magic, known for its great magicians.”

“Magicians?” I said uneasily. I could tell Tsipporah was a halan like me, and as a rule, halani distrusted magicians.

“Not like the kasiri of today,” she said. “The magicians of Erezai were powerful and wise. They had learned the secrets of magic from texts left behind by still older kingdoms. Like our kasiri, they molded the magic with their hands and coaxed it with ancient incantations. But they also harnessed it by painting symbols on stone with pigments ground from cinnabar and azurite. They played music that the magic responded to like a snake to a charmer's flute.”

I frowned. “I didn't know you could do magic with music.”

“Do you like music?” Tsipporah asked.

“I play the violin,” I said. “I just started. But it's my favorite thing to do.”

“After reading books, you mean?” She winked before continuing. “Erezai flourished for over two centuries, but then the cold times came. The summers grew shorter and the winters longer until the crops failed each year. In wintertime, snowstorms swallowed the royal roads and choked off whole cities. The kingdom could not withstand it, so Erezai fractured into city-states: Ashara, Tekova, Atsan . . . what we call the north lands now.”

The chaos of the Ikhad seethed around us, but all I could hear was the old bookseller's voice. She told me how, after the fall of the monarchy, the city-states had relied on their magicians for survival. In Ashara, the kasiri had cast spells to break up the ice on the Davgir River so boats with grain from the south could get through. Those were the days, she said, when the kasiri first set themselves over us halani, who had no magic.

She described how the cities slowly mastered the cold times, breeding hardier livestock and growing new crops adapted to the shorter growing season. In time, the cities reached out and established ties with one another again. And all across the north lands, it was the magicians who governed.

“And so it has been ever since,” Tsipporah said, her gaze inscrutable. “To this day, the kasiri rule Ashara.”

Walking home from the Ikhad with Mother's vegetables in my arms, I felt the lightest I had since Father's death. I floated blindly past the newspaper sellers on the street corners and the smoking grills crowded with ears of roasting corn. In my mind's eye, I saw a barge heaped with golden grain nosing through jagged ice floes while, on the banks of the Davgir, kasiri in black stretched out their hands and sent sparks cracking through the brilliant surface of the frozen river.

O

n a brisk morning in late autumn, I finish a shift at Tsipporah's book stall and start across the bustling Ikhad. The produce aisles are packed with halan servants out shopping for their kasir employers, baskets hooked on their arms. When they're not haggling with vendors, they chat with their friends, pulling their coarse woolen cloaks tight against the cold. A kasir family in black tailor-made coats cuts a path through the crowd, their ivory buttons winking in the sunlight. I give them a wide berth.

While navigating the crush, I keep tight hold of the book Tsipporah let me borrow today. It's a volume on music history. Soon after I first met Tsipporah six years ago, I started helping out at her stall in exchange for the privilege of treating her stock like a free library. Occasionally, I even earn a book to keep for my own.

There's more room to breathe past the bakers and butchers and fishmongers. I linger in the artisans' aisle, enjoying the cheerful chaos of market day. I can't resist stopping at the luthier's stall and gazing at the glossy violins and the bows with mother-of-pearl accents. The luthier sits at a worktable dusted with wood shavings, carving the scroll of a viola. My own fiddle at home can't compare with these expensive instruments. I'm grateful for the violin Mother could afford to buy me, but I still wonder what it would be like to play one of these masterpieces.

As I ease around the corner of a soap maker's stand, a young man runs into me. A halan, judging by his patched sleeves. He mumbles an apology and hurries on.

A tingle of foreboding dances up my arms. As I watch the young man slip past a paper merchant's stall, I know something bad is going to happen, something to do with him.

I turn and press forward, suddenly anxious to escape the market. The last time I had a feeling like this was almost a year ago. My brother and I had walked to the Davgir to see the ice skaters. As we watched from a bridge, a terrible certainty of danger seized me, and I made us go home early. By the time Caleb and I reached our doorstep, the deadliest snowstorm of the winter had begun. A dozen people lost their way in the whiteout around the river and froze to death. I still go cold imagining what might have happened to us.

I shove my way out from under the Ikhad roof, and that's when I see them: two black-clad kasiri on the street corner. The sunlight flashes on their metallic insignia. Even from here, the diamond shape of their badges is distinguishable. These are officers of the First Councilor's Corps, the most feared of all the police who serve the Assembly, the supreme political institution of Ashara.

I stumble back and lean against a roof post, my heart pounding. It feels like some kind of attack, but I know it's the halan intuition, our unpredictable ability to know things we shouldn't logically be able to know. It's unique to halani; the kasiri don't have it.

Whatever the young man who bumped into me has done or is supposed to have done, these officers of the First Councilor's Corps are after him. And Yiftach David, the First Councilor of the Assembly, only deploys his personal corps for subversives.

The diamond-badged officers used to be a rare sight, but lately the seven councilors who make up the Assembly have been adopting more and more policies that hurt halani, like encouraging factory owners to cut their laborers' wages and hire only kasiri for management positions. Now all manner of underground groups have sprung up to agitate for change, provoking a wave of raids and arrests. We halani already outnumber the kasiri two to one. The more resistance grows, the harder the kasir government tries to stamp it out.

I look over my shoulder into the market, searching for the young man. I need to do something before it's too late. Not like when Father died.

But before I can act, the officers charge into the Ikhad. One of them clips my shoulder as he tears by, and I fall down, twisting my knee.

As I struggle to my feet, two more Corps officers dash into the market. Shoppers scream, jostling one another in their haste to get out of the way. Amid the confusion, stalls topple over, sending bottles and bolts of cloth tumbling. Not far from me, a little girl trips over a pumpkin and clings to a roof post, trying to pull herself out from underfoot. She's in danger of being trampled by the mob.

I fight my way over, seize the girl's arm, and lift her to safety.

“Are you all right?”

She nods, her lips trembling.

Dragging her behind me, I pull us out of the thick of the panic only to fall headlong over a sack of potatoes. My palms scrape the cobblestones as the book from Tsipporah skitters away. I swear.

When I stand up, the little girl has retrieved my book and is offering it to me. I finally take a good look at her. She can't be more than eight years old. Her black curls are tied back with a ribbon, and her satin dress is foamy and pink, trimmed with lace like delicate white feathers.

Only a kasir girl would be wearing such a gaudy dress.

Though surprised by her considerate act, I just grab the book and take her hand again. “Come on.”

We take shelter in a recessed doorway as people stream from the square. Within minutes, most of the crowd has cleared out. In the middle of the Ikhad, however, a knot of halani is clumped around the young man with the patched sleeves.

The officers of the First Councilor's Corps close in on the group, raising hideously contorted hands. I can't hear the incantations, but I see colored sparks flash between their fingers. The kasir girl clings to me. I can feel her shaking. The square fills with the bitter scent of magic.

A snake of silver light slithers free from one officer's folded hands and darts toward a woman defending the young man. She collapses, and I stagger as if the spell had struck me.

“Don't look!” I gasp too late, pressing the little girl's face into my cloak.

The halani protecting the fugitive scatter, doubled over from the painful effects of the kasiri's spells. In the aisle of the Ikhad, the young man lies slumped on the ground.

Two officers haul him up and carry him between them. His head hangs down over his chest and his shoes drag along the ground as the police pick their way through crushed vegetables and broken crockery.

Once the police leave the square, someone lets out a wail and rushes to the halan woman lying on the pavement where the kasiri felled her. Others hasten over to help. Vendors begin righting their stalls. Then an old lady breaks free from the cluster of well-meaning shoppers gathered around the unfortunate woman. “She's dead!” she cries, her face stained with anguish.

My head buzzes. For a second, I can't feel my legs under me.

The kasir girl stares up at me with huge, dusky eyes. “Is she really dead?”

I don't know what to tell her.

“Sarah!” A slender woman strides toward us, her face drawn. She's too young to be the girl's mother, and her dark clothes aren't as fancy as the girl's, though they're much smarter than mine. I don't have an immediate impression of whether she's a kasir or a halan, which makes me uneasy.

“What did I tell you about staying by me in the market?” she shouts at the girl.

Sarah hangs her head.

The woman's piercing gaze shifts to me. “Who are you?”

“She saved me,” Sarah blurts out, clutching my arm. “When I fell.”

Her chaperone looks me up and down. “My thanks,” she says stiffly.

Sensing her disdain, I'm about to stalk off when Sarah says, “She's hurt, Channah!” She shows her my grazed palms. “We should drive her home.”

“Sarah, I cannot allowâ”

“If you don't, I'll tell Father you lost me at the Ikhad,” she says pertly.

Channah's lips tighten. I expect her to reprimand her charge, but instead she throws me a furious look. “Very well, Gadin Sarah.”

Sarah grins. I glance about the square, but no one is paying any attention to us. I feel a certain fondness for the girl, even though she's the spoiled daughter of a kasir. So while I'm not sure it's a good idea, I find myself following the kasir child and her chaperone.

A few blocks away, we stop in front of a sleek black automobile. Sunlight spills across the silver plating framing the radiator grill and ringing the bug-eyed headlamps. Channah opens the back door, and Sarah climbs into the auto.

“You may sit in the back too,” Channah tells me.

I've never ridden in an automobile before. I'm afraid to touch the door lest I leave fingerprints on its polished surface. Inside the vehicle, the seats are lined with black leather. Sarah sits near one of the six rectangular windows, an elegant coat of fine black wool laid beside her.

“What's your name?” she asks as Channah gets into the driver's seat.

“Marah,” I say, placing Tsipporah's music history book on my lap.

“Do your hands hurt?”

I check my palms. They've stopped bleeding. “Not much.”

“Channah and IâChannah's my tutorâwe were going to go to the menagerie today,” Sarah says. “At least, before . . .” She goes quiet, looking out the window in the direction of the covered market.

I don't know what to say. I'm remembering the deadly silver light, the old woman's grief.

“Where to?” Channah asks from the driver's seat.

“Five, Street of Winter Gusts, please,” I say. “It's in Horiel District. South ofâ”

“Oh, of course. I have cousins in Horiel. Not a bad sparker district.”

I jump when she says “sparker.” It's slang for halan, an ironic name coined by kasiri precisely because we

can't

produce sparks from our fingers. Over time, halani embraced the term. It's all right for us to refer to ourselves that way, but coming from a kasir, it's an insult.

“You said a bad word!” Sarah pipes up.

“You're right,” her tutor says. “I'm sorry.”

Glancing over her shoulder, Channah gives me a knowing look, and I understand at last that she is a halan. Tutor to a kasir child is one of the rare positions that could be filled by either a kasir with few prospects or a very well-educated halan. Using the word “sparker” isn't exactly the way for halani to demonstrate good breeding, but I don't mind. Maybe Channah isn't as snobbish as I first assumed.

The auto lurches forward, and the street starts to slide under the hood. I grab the seat with my hands. I can hardly bear to watch as we barrel around the first corner.

“What's your book about?” Sarah asks eagerly. “Does it have stories?”

“This?” I say, tapping its stained clothbound cover. “No. It's about music history. I'm not sure you'd like it.”

“Tell me a story, then,” Sarah demands.

The auto careens around another corner. The sight of the buildings swinging past the windshield makes my stomach pitch.

“All right,” I say. Anything to forget about the horror of the Ikhad. I draw a deep breath. “Here's a story about Frost. Have you heard of her?”

Sarah shakes her head, her face bright with anticipation.

“Frost was a girl who lived at the beginning of the cold times. She was small, but very quick and strong, and she could walk through snowstorms that lasted for days without getting cold. She tramped all over the north lands wearing snowshoes and animal furs, and everywhere she went a white fox followed her. His name was Silver.

“One day she met a group of traders in the forest. They were traveling the long road from Atsan to Ashara, but their sleds were stuck in the snow, and their horses couldn't pull them free.”

“Why didn't they use magic to melt the snow?” Sarah asks.

I frown. “They were halani, I guess. There aren't any kasiri in this story.”

“No kasiri?”

Channah gives a pointed cough from the front seat.

“At the beginning of the cold times, the difference didn't matter so much,” I say quickly.

Sarah accepts this. “So what did Frost do?”

“She called her friends the wolves and harnessed them to the sleds in place of the horses. The wolves carried the traders' cargo through the forest while the horses trotted behind, led by Silver the fox. When they came out of the woods, though, the wolf pack would go no further. They refused to journey beyond their territory.”

I pause. The little girl beside me is listening raptly.

“So Frost called her friends the ravens. They took up the harnesses in their beaks and talons and flew, so that the sleds skimmed over the snowy fields. There were so many ravens their wings darkened the sky.

“Before long, the traders glimpsed the city of Ashara on the horizon. They were overjoyed to have almost reached their destination, but then they noticed the ravens flying away. As soon as the city came into sight, they would go no further because they would not go near where humans lived. And so the sleds were left in the snow once again.”

At that moment, the auto squeals to a halt on the Street of Winter Gusts. “We're here,” says Channah.

“But I want to know the end of the story!” Sarah says.

I start to go on, but when I catch sight of Channah's irritated expression in the rearview mirror, I falter. “Maybe I can tell you another time.”

I thank Sarah and her tutor and jump out, eager to escape the vehicle and its rumbling engine. Two retired men walking up the block stop and stare at the shiny auto, so out of place against the dull brick of the apartment buildings. I give Sarah a little wave, and she watches me mournfully through the window as Channah drives away.