Spice

Authors: Ana Sortun

In memory of my brave and loving father, Gary Sortun,

who gave me creativity

.

Contents

PART I

: SPICES

1.

The Three Cs: Cumin, Coriander, and Cardamom

2.

Saffron, Ginger, and Vanilla

3.

Sumac, Citrus, and Fennel Seed

4.

Allspice, Cinnamon, and Nutmeg

5.

Favorite Chilies: Aleppo, Urfa, and Paprika

6.

Three Seeds: Poppy, Nigella, and Sesame

7.

Gold and Bold: Curry Powder, Turmeric, and FenugreekPART II

: HERBS AND OTHER KEY MEDITERRANEAN FLAVORS

8.

Dried Herbs: Mint, Oregano, and Za’atar

9.

Fresh Herb Combinations: Parsley, Mint, Dill, and Sweet Basil

10.

Oregano, Summer Savory, Sage, Rosemary, and Thyme

11.

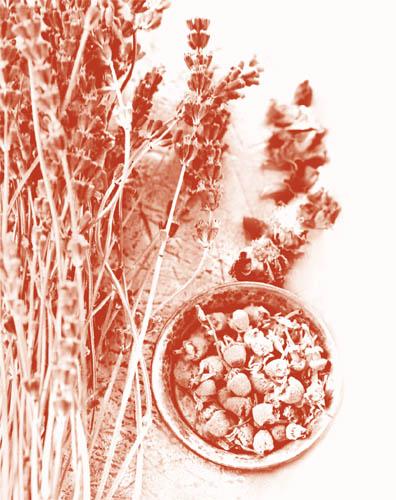

Flower Power: Cooking with Nasturtium, Orange Blossom, Rose, Chamomile, Lavender, and Jasmine

12.

Rich, Creamy Flavor: Nuts, Yogurt, and Cheese

Resources

What makes each country’s food taste unique? What gives it life? In the Arabic foods around the Mediterranean and Middle East, the answer is spice.

In cooking school in Paris, I was taught that the way to add flavor to a dish was with fat. The rule still lingers that where there is fat there is flavor, and so French-influenced chefs regularly use extra butter or heavy cream to add richness to a dish. I have nothing against the use of fat, but my experience has taught me that it is not the only way to achieve flavor.

A

ll chefs think about how dishes taste and appear, but few consider how the food makes people feel after they’ve eaten. In my travels to the eastern Mediterranean region, I learned that the cuisines feel rich and are full of flavor because of the artful use of spices and herbs, flowers, nuts, and cheese. I’ve brought these lessons home to Oleana, my restaurant in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where we make dishes absolutely alive with flavors that leave guests ready for a night of dancing—not weighed down and ready for bed.

My journey as a chef started with my grandmother Betty Johansen, who was an excellent home cook and who instilled in me the love of eating good food. My grandmother was a simple cook, but she made everything from scratch, using the freshest seasonal ingredients, straight from the family farm in Kent, Washington. She made her own bread, butter, ice cream, salad dressings, pickles, and canned fruits. The memory of her homemade rolls—fresh and warm out of the oven, slathered with homemade butter—still makes my mouth water.

At age fourteen, I started washing dishes in a small neighborhood restaurant called the Santa Fe Café in Seattle. That led to other kitchen work, and I soon began assisting at a local cooking school in order to learn more basic skills. Meanwhile, I studied French privately and intensely for over two years, until I passed a fluency requirement exam, and when I turned nineteen, I left for Paris. It was there that I trained in classic, regional French cooking and wine at La Varenne, while working at the school to pay for my education. The best lesson I learned in France is the importance of fresh, high-quality ingredients. I learned to shop at farmers’ markets, where I began to recognize the difference between truly fresh vegetables and those that had been shipped.

Back in the United States, I worked for Moncef Meddeb—a Tunisian-born chef famous for bringing upscale, cutting-edge Mediterranean and French food to a Boston dining scene steeped in traditional New England fare—as the chef at Aigo Bistro, in Concord, Massachusetts. Under his tutelage, I came to understand how the Arabic world has influenced French cuisine.

Moncef pushed me toward a deeper understanding of food and flavors. I was twenty-four at the time, working out my own style and identity in the kitchen. One night after work, he called, and I told him I was starving. He told me that I should keep fruit around for late night snacks, but all I really wanted was bacon and eggs. At this point, Moncef launched into a 20-minute discussion about oranges. He described in depth the fragrant spray of oils releasing as the skin of the orange is broken and the juices running down one’s hand as the fruit is peeled. After listening to him, my hunger for that orange was nearly unbearable. What happened to me that night as a chef was a milestone: I understood food more intimately. I was able to taste food when I thought about food.

As the chef at Casablanca restaurant in Harvard Square, where I worked for five years, specializing in the cuisines of the Mediterranean rim, I began to come into my own. It was on my trip to Turkey in 1997 that I had a revelation, and my journey in spice began.

That year, the owner of Casablanca, Sari Abul-Jubein, sent me to Gaziantep in southeastern Turkey, the country’s gastronomic capital. The very thought of Turkey was foreign to me—I envisioned flying carpets and covered women hidden deep in the veils of purdah. I flew through Istanbul and went straight to Gaziantep, where I stayed with Ayfer Unsal, a friend of Sari’s and a journalist and author of Turkish cookbooks. Ayfer welcomed me with a lunch staged by some of the townswomen. Each of them had brought her family’s specialties in my honor: everyone had a different version of the bulgur-based

köfte

or

kibbeh

, some with lamb, others with potato and pumpkin; salads dressed with sweet-tart pomegranate molasses; fresh and intriguing vegetables spiked with the spice and herb combinations which are now staples in my kitchen. It was a feast, the likes of which I had never before experienced. I stayed with Ayfer for just over a week, studying her as she cooked, going with her to the market—where ordinarily women do not go—as well as baklava shops, pita bakeries, pistachio growers, and artisans’ shops.

I left Gaziantep for Istanbul where Ferda Erdinc, a friend of Ayfer’s, took me on yet another intense food adventure. Ferda is active in the food world, both as a writer and restaurant owner. Through these two women, my misconceptions about Turkey were replaced with a deep respect for the country’s culture and cuisine. Istanbul itself was a revelation. More westernized than Gaziantep, the city offered food and dining experiences that were more sophisticated than what I’d found in the south. I continued to dine, sometimes eating elaborate, multicourse meals. Inevitably, these occasions would end in dancing, and I got hooked on the culture as well as the cuisine. It was during this trip that I began to home in on the Arabic use of innovative herb and spice blends to extract maximum flavor in cooking. I had found spice.

Later, back in Boston, I began processing what these two women had shown me and gradually incorporated what I had learned. Other than the sophisticated fusion of Western technique with the exotic spice blends of the Middle and Near East, what impressed me most about my experiences with Turkish cuisine were those delicious multicourse meals after which everyone left feeling energized. So I decided to open Oleana, a restaurant that introduced people to the exciting foods of the Arabic Mediterranean, where customers would leave their tables ready for a night of dancing.

So many Mediterranean restaurants focus on the cuisines of Spain, the south of France, and Italy, where large meals usually put me in bed, feeling heavy and tired. I want people to experience the Arabic flavors of North Africa, the eastern Mediterranean region, and the Ottoman empire, as these cuisines have contributed hugely to world gastronomy but haven’t been explored much in the United States.

At Oleana, we make healthful, seductive, and exotic food approachable to a wide variety of customers. Arabic foods intrigue me so much that I can’t sit still when I eat at a great Turkish restaurant. I get so excited about the flavors and curious about their kitchens that I practically jump out of my chair. I’d like to share that enthusiasm with you—my readers, friends, and customers—and welcome you in finding spice.

People ask me so many questions about spices and herbs—their usage alone and in combination. What can I do with coriander? What spices go well with lamb? What can I do with all the mint in my garden?

U

nlike other cookbooks, which are most often organized by meal order (salads, appetizers, main courses, etc.) or ingredients (chicken, vegetables, etc.), this book is organized by spice and herb groupings or families. In chapter 1, for example, I’ve grouped cumin, coriander, and cardamom together because they complement one another and can be used in similar applications. This way, you can become familiar with the wonderful individual qualities of each spice as well as the ways you can combine them to enrich your dishes. And you’ll learn which spices go well with different foods.

By organizing the book this way, I’m hoping to provide you with a map that you can use as you embark on your own spice journey.

Enjoy!