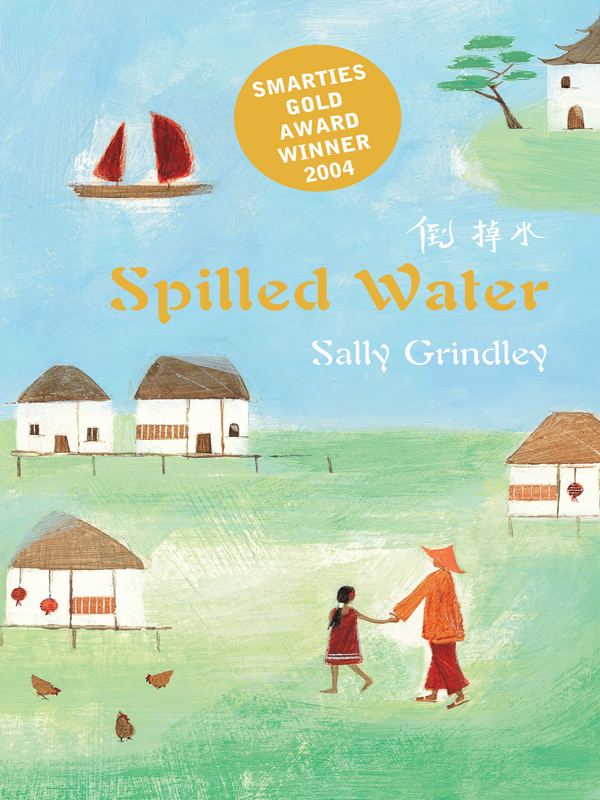

Spilled Water

Authors: Sally Grindley

Spilled Water

Sally Grindley

First published in Great Britain 2004

Copyright © Sally Grindley

This electronic edition published 2009 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

The right of Sally Grindley to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 36 Soho Square, London W1D 3QY

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 978-1-40880-731-6

www.bloomsbury.com/sallygrindley

Visit

www.bloomsbury.com

to find out more about our authors and their books. You will find extracts, authors interviews, author events and you can sign up for newsletters to be the first to hear about our latest releases and special offers.

For James, Chris and Sam, who are my pride and joy

Contents

To Market

I loved my baby brother, until Uncle took me to market and sold me. He was the bright, shiny pebble in the water, the twinkling

star in the sky. Until Uncle took me to market and sold me. Then I hated him.

‘Lu Si-yan,’ Uncle greeted me early one summer morning, ‘today is a big day for you. From today, you must learn to find your

own way in the muddy whirlpool of life. Your mother and I have given you a good start. Now it is your turn.’

My mother stood in the shadows of our kitchen, but she didn’t look at me and she didn’t say a word. Uncle took me tightly

by the wrist. As he led me from the house, my mother reached out her hand towards me and clawed the air as though trying to

pull me back. Then she picked up my little brother and hid behind the door, but I saw her face wither with pain and, in that

moment, fear gripped my heart.

‘Where are you taking me, Uncle Ba?’ I cried.

‘It’s for the best,’ he replied, his mouth set grimly.

‘You’re hurting my arm,’ I cried.

He pulled me past the scorched patchwork terraces of my family’s smallholding, scattering hens and ducks along the way, and

out on to the dusty track that led steeply up to the road. There, we walked, Uncle brisk and businesslike, me dragging my

feet in protest, until we came to the bus-stop.

‘Where are we going, Uncle Ba?’ I whimpered this time.

‘To market,’ he said.

‘What are we going to buy?’ I asked.

The Happiest Soul

on Earth

Everybody loved my father. My mother used to say that he was the happiest soul on earth. When you were with him he made you

feel happy too.

When there was just me, he used to lift me on to his shoulders and gallop down to the river, where he picked me up by the

armpits and dangled my feet in the water. I screamed at the cold, but then he put my feet in his jacket pockets, one in each

side, and we galloped off again, laughing all the way.

When there was just me, he sat me in his rickshaw and cycled along the road, weaving from one side to the other, bump, bump,

bump across the cobbles, singing at the top of his voice. I lurched up and down on the seat, yelling at him to stop but wanting

him to carry on.

When there was just me, he taught me to play chess and wei-qi, and sometimes I won, but I knew that he was letting me. We

played mahjong with Uncle and my mother. Father and I made silly bird noises every time it came to the ‘twittering of the

sparrows’, while Uncle tutted and my mother rolled her eyes heavenwards in mock exasperation.

We never had much money, but I didn’t really notice because neither did anyone else in our village. Father’s favourite saying

was, ‘If you realise that you have enough, you are truly rich’, and he believed it. ‘We have fresh food and warm clothes,

a roof over our heads (a bit leaky when it rains) and a wooden bed to sleep on. What more can we ask for?’ he demanded. ‘And

not only that,’ he continued, ‘but I have the finest little dumpling of a daughter in the whole of China.’

My parents worked hard to make sure that we always had enough. Father set off early in the morning, his farming tools over

his shoulder, to tend the dozens of tiny terraces of vegetables that straggled higgledy-piggledy over the hillside above and

below our house. He dug and sowed and weeded and cropped throughout the numbing cold of winter and the suffocating heat of

summer. In the middle of the day, he returned home clutching triumphantly a gigantic sheaf of pakchoi, a basin of bright green

beans, or a bucket full of melon-sized turnips.

‘Your father can grow the biggest, tastiest vegetables on a piece of land the size of a silk handkerchief,’ Mother used to

say, and I would skip off to help him because I wanted one day to grow the biggest, tastiest vegetables as well.

Mostly, I spent the mornings with Mother, feeding the hens and ducks and collecting their eggs which were scattered around

our yard. There were slops to be taken out to our pig and fresh straw to be laid. Once a week, along with our neighbours and

their children, we carried our clothes down to the river to wash them. That was the best day. When it was hot, we children

pulled off the clothes we were wearing and charged into the river, splashing wildly and shrieking our heads off. We learnt

to swim very young and raced backwards and forwards through the sparkling waters. As soon as we were back on the shore, our

mothers attacked us with soap, then we dashed into the water again to rinse it off, before running around in the sun to dry.

In winter, the river sometimes froze for days on end. Some of the older children went skating on it, but Father said they

were foolish because they might fall in.

Mother was ready with soup and rice when my father returned at midday. He used to sit me on his knee and ask me what I had

been up to all morning. I made up stories about fighting dragons and escaping from haunted temples and he would sit there

saying, ‘Did you? Did you really? What a morning that must have been!’ until we dissolved into fits of giggles and Father

said, ‘I hope the rest of the day will be quieter for you.’

In the afternoons, Father returned to his terraces, or he would walk several miles with other villagers to work on the rice

fields that they shared. Mother went to the village to shop and to gossip, and I went with her to play with my friends. Nobody

minded us dashing in and out of the shops in a boisterous game of hide-and-seek, and the old men smiled as we peered over

their shoulders to watch them playing cards on wobbly foldaway tables in the street.

Back home again, Mother and I prepared the evening meal, ready for my father’s return. Sometimes, if he was early enough,

he took his boat out on the river to fish. He would let me go with him if I promised to be ever so quiet. Once we caught the

biggest carp anyone in the village had ever seen. If we stood it on its tail it was taller than me! We took it to market and

sold it for so much money that Father was able to buy us each a new pair of shoes.

Father never worked on Sunday afternoons. If necessary, he worked still harder during the week in order to free himself for

his ‘family time’. On Sundays, he sharpened all our kitchen knives, selected the very best vegetables from our farm, killed

one of our chickens, and set to work with spices and herbs and ginger and garlic in preparation for our evening meal. This

was his favourite time. We would sit at the table and talk to him as he chopped away. We were not allowed to help.

‘You have had to prepare my meals all week,’ he would say to my mother. ‘Now it is my turn to prepare your meal.’

If ever Mother argued that he had been working all week long on the farm and should put his feet up, he simply said, ‘That

is different, and in any case I enjoy cooking. I want to cook, and I want you to put your feet up.’

Mother grumbled good-humouredly at his stubbornness, but we knew that he loved every minute of his weekly role as chef. And

he was good at it. The meals we ate on Sunday evenings were the best, Mother was happy to admit it. When they were over, we

sat down as a family and watched television. It didn’t matter what was on – it was just the being there together that we loved.

To Market

Uncle remained silent, sucking hard on a cigarette, leaving my question hanging in the heavy morning air, until a bus came

along and he pushed me aboard. Two women I recognised from a nearby village were already sitting inside. They immediately

asked us where we were going. Uncle said a name that meant nothing to me, while making it clear that he did not wish to discuss

his business any further. I heard one of the women whisper that, my goodness, we were going on a long journey, and the two

of them wondered aloud what on earth we might be going all that way for. Uncle ignored them, while I tried to make sense of

the disturbing turn of events that had thrown my life into confusion.

I gazed out of the window, slightly comforted to realise that the landscape was still familiar. Father and I had come this

far many a time in the past, bump, bump, bump in his rickshaw. Then the bus stopped and the two women clambered off, waving

goodbye to me, wishing me a pleasant journey. They headed in the direction of a street lined with colourful stalls. I saw

that it was the market where my father always used to sell his vegetables and where we had sold his enormous carp.

‘Why aren’t we going to that market?’ I asked.

‘Too small,’ said Uncle brusquely.

The bus rumbled on again, leaving the world I knew behind it, to climb, twist, speed through countryside, villages and towns

I had never seen before. Gradually the motion of the bus sent me to sleep.

I woke up to find myself stretched out across Uncle’s lap, his arm curled round my shoulder. When he saw that I was awake,

he pulled his arm away abruptly, as though he didn’t want me to think that he was showing any affection for me. I sat up and

looked around. The bus was empty apart from us. Outside, it was growing dark. How many hours had we been travelling? We’d

left home soon after breakfast. We’d had nothing to eat since. I was ravenous.

‘How much further?’ I said. ‘I’m starving.’

‘Not long,’ said Uncle. He reached in his pocket and gave me a piece of cake which my mother must have baked.

‘When are we going home again?’ I asked.