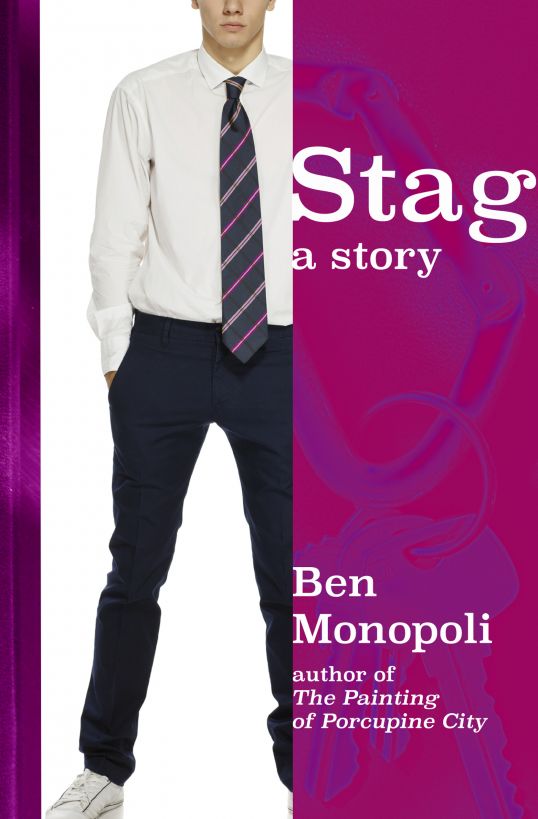

Stag: A Story

Authors: Ben Monopoli

Tags: #coming of age, #middle school, #high school, #gay fiction, #coming out, #lgbt fiction

STAG

a story

Ben Monopoli

Stag: A Story

By Ben Monopoli

Copyright © 2013 by Ben

Monopoli. All rights reserved.

Smashwords

Edition

No part of this publication

may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any

means without the express written permission of the

author.

This is a work of fiction.

Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of

the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any similarity

to real persons, living or dead, is entirely

coincidental.

Cover photo of model by

Paffy69. Cover design by the author.

www.benmonopoli.com

STAG

Stag

.

I remember hearing that word, sensing

immediately the freedom in it. Stag. It was a hard word, angular,

macho, as navy-blue as military. And cool. Unimpeachable. It had no

weakness, could not be questioned. It was strong.

The first of us to use it was Boyd Wren, and

he used it well aware of its power. Someone had asked him who he

was bringing to the dance.

“No one,” he said. “I’m goin stag.”

Stag.

Stag.

We whispered it, reveling in it, the five of

us, the five bottom rungs on the eighth-grade ladder. Even those of

us who’d never heard the word before understood its meaning. All

except Dwight Macklin, who asked.

But it couldn’t be explained; everyone else

understood this. To provide a definition would be to reduce its

power. It would be like explaining a magic trick.

So Boyd merely said again, “It means I’m goin

stag.”

When the word came out of his mouth you

watched for his back to straighten and for his fists to press

against his hips. You watched for his smudged glasses to

disappear.

“I’m going stag too,” said Tyson Cordray.

“Me too, I’m goin staaag,” said Michael

Alonso, the weird one.

“How about you, Ollie?” said Boyd.

“Stag,” I said.

My first choice—skipping the dance—wasn’t an

option. This was the big one, the Grad Dance, the last before high

school. People like me who had successfully skipped three years of

middle-school dances could not skip the Grad Dance. You went

because everyone had to be there. The grade policed itself with the

rigid enforcement of a grandmother making sure all the cousins

showed up for Christmas. There was no way out. I couldn’t even try.

So I clung to the word.

*

“I’m going stag,” I told my mother, only

because she asked; I never brought up the dance on my own. I tried

not to acknowledge it at all.

We were walking up the rickety spiral steps

of the town’s only seamstress. Certain preparations needed to be

made for the dance, and my mother was intent on making them, even

excited. My suit needed to be let out.

“Oh, Oliver, you should ask a girl,” said my

mother, looking down from a higher step. “What about Nadia

Cummings?”

“All my friends are going stag.” I held the

word up at her like a shield.

“Or Jasmine Lorange?”

Names rained down. While we sat in the shop’s

stuffy waiting area she listed all the girls I’d ever been on a

soccer team with, all the girls we’d seen at gymnastics class and

town yard-sales.

“No one is taking anyone,” I said.

The seamstress, an old woman overworked in

this season of dances and proms, sent me behind a curtain to put on

my suit and then tugged at my crotch and my shoulders, taking

measurements.

“Have you asked a pretty girl?” she said,

smiling around the pins in her mouth.

“No,” I said. “Going stag.”

*

My four friends saw stag as a way to polish

the inevitable. It insulated them from being mocked for being the

kind of boys who couldn’t land a date. A boy going stag wasn’t

going alone, he was choosing to go alone. The difference between

those things, for an eighth-grader, was everything.

For me stag offered something more. For me it

was a relief, a reprieve from a rite of passage I had come to

understand I wasn’t destined for. I whispered it to myself at every

mention of the dance, like a spell to ward off suspicion. Stag. For

me it kept things at bay.

Talk of the dance, all year a hum, grew to a

buzz, a thump, a clanging in the school hallways. Girls talked

about where they were having their hair done; boys talked about

buying corsages. Invitations to go to the dance were delivered

through the bolder proxies of bashful friends. At lunch, in

classrooms, on the bus, notes were passed. I pretended not to see.

That trick for monsters: if I closed my eyes and counted to three,

would it all go away?

*

At the end of one day when I opened my locker

a piece of paper fell out. Notebook paper folded into a triangle

and decorated with hand-drawn orange musical notes. I closed my

eyes and counted. One, two, three.

“What is that!” Dwight gasped from the

cluttered locker beside mine. He was ready for it to be a treasure

map, a ransom note, but I knew it was neither of those.

“Just from my mom,” I said, slamming the

triangle deep into my backpack.

One, two, three. One, two, three, one, two,

three.

I thought about throwing it away without

reading it. I couldn’t be responsible for something I never saw. I

owed no one an answer if I never saw a question. I was going stag,

didn’t they know? The note was an insult. But it was an armed bomb

too. One I needed to defuse before it blew up.

I opened it on the bus, slunk down in the

green vinyl seat with my knees pressed high against the back of the

seat in front of me. Within the pocket of my lap I unfolded the

triangle. In orange ink it read:

Oliver. Would you like to go to

the Grad Dance with me? (Jessica Parson) Please check one and put

this in Locker 341. __ Yes __ No. From Jessica Parson. PS: I’m good

at dancing, you’ll see.

Some, but not all, of the I’s were

dotted with circles.

Jessica Parson, only Jessica. A weight

lifted; I exhaled and my knees slid down the green vinyl. Jessica

was a girl it was OK not to want to go to this dance with. Any

dance with. She was a girl no one would want to go to a dance with.

My friends would excuse this, based on Jessica’s ever-present

kitten sweatshirts, her big buck teeth, her faded stretch-pants

everyone said smelled like horse manure because she lived near a

farm. They would reject it. To have help in rejecting a girl for

not being good enough—this was a fine disguise.

“She asked you?” Tyson said, affronted, when

I showed the guys the note. “That wench.”

“I bet she’s going to wear h-h-horse poop

perfume to the dance,” Michael said, laughing, rubbing the heel of

his hand against his perpetually itchy chin.

“I feel so dirty now,” I whispered

dramatically. “I need a chemical baaath.”

“Let’s see that note again,” said Boyd,

holding out a sturdy hand. I gave it to him. Using his knee as a

table, he drew a blue X on the line beside

No

. Then he

paused, touched the pen cap to his lips, then circled the

No

.

“Write on it

In your dreams Jessica

,”

said Michael. “Write on it

You smell like shit

.” He had the

devilish grin of a boy new to swearing.

“This is fine like this,” Boyd said.

He folded the note in a series of halves and

handed it back to me. Between first and second periods I raised it

to the ventilation holes of Jessica’s locker.

I closed my eyes and counted to three. Paper

whisked against metal and it was gone.

As the days slid by everything started to

become all dance, all the time, an onslaught too overwhelming for

my anti-monster trick. It came from everywhere—the obvious places,

but even my own bedroom.

“We should buy you new shoes for the dance,”

my mother said. My suit was back from the seamstress and she’d

realized it was still incomplete.

“I don’t need shoes,” I said, wedging the

suit into the back of my closet, where I could better pretend it

didn’t exist. Plastic hangers clattered to the floor. “I can wear

my church shoes.”

“But those aren’t very fancy. Don’t you want

to look nice? People are going all-out for this.”

She was sitting on the end of my bed,

cradling her chin with one hand while her elbow rested on her knee.

She was looking at me as though I were the most mysterious thing in

the universe.

“Who cares if I look nice?,” I said, shutting

the closet door and letting my hand slide damply off the knob. “Can

I go outside?”

She sighed, pressed her knuckles to her lips.

“You’re going to have a lousy time at this dance, Oliver. Do you

know why? Because you’ve already decided to have a lousy time.”

“I’m going outside,” I said, leaving her in

my room and taking the stairs two at a time.

In biology class I had been thinking about my

suit, thinking that if I didn’t wear the jacket to the dance—if I

only wore a shirt and pants—it might not seem so official, when a

finger poked my spine. It was a poke full of intention, as though I

were being summoned from a lower floor. I pretended not to feel it.

I knew Amy Langley was sitting behind me. I looked toward the

blackboard and closed my eyes. One, two, three one two—

“Oliver,” she whispered, and after hesitating

I turned a little in my seat. “Hi,” she added.

“Hi.”

“Are you going to the Grad Dance?”

“... Yuh.”

“Are you going with anyone?”

I shook my head slowly, slowly, like a person

trying to outwit quicksand.

“Taylor wants me to ask if you’ll go with

her.”

“Oh.”

“She really wants a flower, even just a

little one.”

“Oh. OK.”

“Good! I’ll tell her.”

I faced forward, almost dropped forward. My

fingers were leaving wet dimples on my textbook pages. What had

just happened? What was happening? Why had I not told her about

stag, wielded it like the weapon it was?

After a few seconds with my eyes shut tight I

felt another poke. When I turned Amy pointed to the far corner of

the classroom. Taylor, blushing, looked up from her doodling,

glanced at me, smiled.

At the end of the day when we were all in the

hall putting on our backpacks she came over to my locker. She

seemed to peek out from behind her brown bangs and long

eyelashes.

“I’m excited we’re going,” she said. She

looked happy. I couldn’t fathom why. I wanted her to leave me

alone. Why was she doing this to me? What had I done to her? “I

heard Jessica was going to ask you, but then she decided to go

alone instead.”

“Oh.”

“So.”

“Yeah.”

“So like do you want a ride to the dance?”

she said. “My mom could pick you up?” She was biting her lip,

clicking her Jelly-shoed heels together awkwardly.

“My mom’s already driving me. So.”

“Well... maybe your mom could pick me up,

then?”

“We don’t know where you live, though,

so....”

“Oh. OK.” She wasn’t stupid, she was deciding

not to press it. “So.” Her heels stopped moving. “We’ll meet up at

the dance?”

“Yeah I’ll just see you there, I guess?”

I hated her for making me act like a jerk but

I didn’t know what else to do. Was being a jerk better than

pretending to want this? I knew only those two options: lead her on

or scrape her off. The truth was too much. It was too much; I was

thirteen. No one in this school was like me. No one in this town,

as far as I knew, was like me. Bad people were like me. Dead people

were like me.

“What was that?” Boyd Wren said after she’d

walked away.

His voice made me realize there were other

people around, people who were knowing. This was already

happening.

“Not stag anymore?” Boyd added.

“She asked me, I didn’t know how to say

no.”

“She’s cool,” he said casually. He scratched

at my locker with his thumb. “Me, I figure I’ll still go stag. I

don’t like to be tied down.”

*

This was the opposite of Jessica. I was

afraid to tell the other guys about Taylor. The reason Taylor was

so devastating was that she would’ve been, should’ve been, exactly

the girl for me. Cute. My height. Perfect. But when you’re hiding,

like I was, the sweetest girl is the most dangerous. Her perfection

was like a looming spotlight three steps behind an escaping

prisoner.