Stalin's Daughter (10 page)

Authors: Rosemary Sullivan

Svetlana’s school years coincided with the cult of personality. Stalin’s image appeared everywhere, and he began to be hailed with grandiose epithets, from the Great Helmsman to Soviet Women’s Best Friend. His relative Maria Svanidze insisted this wasn’t personal vanity. According to her, Stalin claimed that

“people need a tsar, that is someone to whom they could bow and in whose name they could live and work.”

23

This disclaimer is not entirely convincing, though it would seem that shrewd political calculation about the impact of propaganda, as much as megalomania, motivated Stalin’s cult of personality. In any case, Svetlana climbed the stairs to meet her father’s face every morning.

Because she was used to private tutors, the school was a shock. The first day, she walked into the boys’ bathroom, as she had always done at home among her brothers and cousins, and was ever after known as the girl who walked into the boys’ toilets.

24

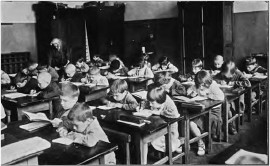

Svetlana in her classroom at Model School No. 25 in Moscow, sitting at the third desk in the second row, in 1935.

Model School No. 25 was no ordinary school. It was considered the best in the country. As one former pupil described it, it was “the school where the big-shot children went.”

25

So rarefied was the world of Model School No. 25 in relation to what was happening in the rest of the country that it was like stepping through the looking glass. Palms and lemon trees dotted the hallways, and there were white tablecloths on the tables in the cafeteria. The students included the sons and daughters

of the famous and powerful: the children of actors, writers, an Arctic explorer, an aviation engineer, members of the Comintern’s Executive Committee and the Politburo, and other high government officials. There were many limousines.

Model School No. 25 was a Soviet lycée with very high scholastic standards. By 1937 the library, with its resplendent banner,

WITHOUT KNOWLEDGE, THERE IS

NO COMMUNISM

, had twelve thousand volumes and subscribed to forty journals and newspapers. Beside the library was a quiet room where children played dominoes, table croquet, and chess.

26

The school had clubs in theater, ballroom dancing, literature, photography, airplane and automobile modeling, radio and electrotechnology, parachute jumping, and chess. The boxing club and track club trained on the surrounding streets. There were sports competitions, a rifle team, and volleyball tournaments. A doctor and a dentist were in residence. The children went on excursions to Moscow’s famous Tretyakov Gallery and to Tolstoy’s estate, and they vacationed at sanatoriums on the Black Sea. Even as the train carried them through the famine-stricken Ukraine on their way to their Crimean summer camps in the early 1930s, and though the station platforms were crowded with hungry people devastated by collectivization, students remained under the spell of their school. Their teachers did not discuss the famine.

Model School No. 25 was treated as a “shopwindow on socialism,” and thousands, including foreigners, came to visit. Reporters and photographers would follow in their wake. The American singer Paul Robeson placed his son there in 1936, though under an assumed name. When the school needed money, a letter from the director to Stalin or Kaganovich would get a response. One American visitor, Joseph C. Lukes, wrote in the visitors’ book: “The standards of lighting, heating, ventilation and cleanliness are up to American standards.”

27

Soon

the school got more money to renovate and upgrade. Model School No. 25 was meant to be better than American schools.

28

There were schools outside Moscow that the foreigners did not visit, schools where, by the early 1930s, students went without paper (they wrote notes in the margins of old books) and pens were rationed. Because of a shortage of desks, classes were taught in shifts. Schools closed for lack of firewood or of kerosene for lamps. Outside the capital, the devastation caused by forced collectivization and the attacks on the kulaks, which led to widespread famine, meant that often as many as 40 percent of the students dropped out. Many of them had died.

29

In 1929, Andrei Bubnov, commissar of enlightenment and head of the Communist Party’s Agitation and Propaganda Department (Agitprop), called upon all schools “to immerse themselves in a class war for the transformation of the Soviet economy and society.” Students and teachers at Model School No. 25 were meant to internalize the Stalinist credo: “a respect for obedience, hierarchy and institutionalized authority; a belief in reason, optimism and progress; recognition of a possible transformation of nature, society, and human beings; and an acceptance of the necessity of violence.”

30

Like all Soviet schools, Model School No. 25 promoted indoctrination with banners hung in the hallways:

DOWN WITH FASCIST INTERVENTION IN SPAIN

or

LIFE HAS BECOME BETTER, COMRADES, LIFE HAS BECOME MORE JOYFUL

(Stalin’s famous 1935 pronouncement).

31

All Soviet children were trained in Communism. First they were Octobrists, then Pioneers, then Komsomols. One became an Octobrist in first grade on November 7 (October in the old, Julian calendar) to coincide with Revolution Day. Everyone got a red star with a white circle in which was the head of baby Lenin.

One became a Pioneer in third grade. Children received

triangular red scarves that they were required to wear every day. They also got pioneer pins with the slogan

ALWAYS READY!

Svetlana proudly wore her Pioneer uniform and marched enthusiastically with the Model School No. 25 contingent in the annual May Day parades across Red Square. “Lenin was our icon, Marx and Engels our apostles—their every word Gospel truth,” she would say in retrospect.

32

And it went without saying, her father was right in everything, “without exception.”

However, there was a paradox at the core of the Model School. When Svetlana started there in 1933, only 15 percent of the teachers and administrators belonged to the Communist Party. Many of them had questionable backgrounds as part of the prerevolutionary nobility, the White Army, religious organizations, or the merchant class. Model School No. 25 managed to be relatively democratic and fostered an ideologically unacceptable individualism.

33

Some of its graduates became critical opponents of the Communist system, working as reformist editors, historians, attorneys, and human-rights activists.

It is compelling to compare the reputations of Stalin’s children at the school; they were polar opposites. Most of Vasili’s schoolmates remembered him as an amusing and rambunctious boy who was constantly in trouble. His closest friend was called Farm Boy (Kolkhoznik)—the boy’s family had recently migrated from the countryside; his mother scrubbed the school floors.

34

Vasili was notorious for his pranks. A church had once stood beside Model School No. 25, and the mounds of graves in its abandoned graveyard were still visible. One of Vasili’s favorite escapades was to sneak into the graveyard with his buddies to dig up bones.

35

And he was already known for his cursing.

When reprimanded by schoolteachers, he would say he would do better, “remembering whose son I am.”

Still, his fellow students considered themselves his equals. When he broke a window and blamed someone else, they beat him up. When he harassed a boy who had poor eyesight, they voted to expel him from the Komsomol.

36

There was an amusing moment when he deliberately interrupted a film being shown to visiting teachers and his instructor shouted, “Stalin, leave the room.” They all froze until they saw the diminutive Vasili storm out. Whenever he attempted to intimidate the administration and teachers with his name, reports were sent to Stalin, who had relayed firm instructions that his children were to be treated like everybody else.

37

Vasili was clearly afraid of his father, but he was already presuming on the authority his name conferred. Aged twelve, he wrote to Stalin. He had taken to calling himself Vaska Krasny (Red Vaska), presumably to please him:

AUGUST

5, 1933

Hello Papa.

I got your letter. Thank you. You write me that we could leave for Moscow on the 12th. Papa, I asked the Commandant if he could personally arrange for the wellbeing of the teacher’s wife. But he refused. So the teacher arranged for her to work in the barracks of the workers…. Papa, I send you three rocks on which I have painted. We are alive and well and I am studying until we meet again soon.

Vaska Krasny

38

In this instance Vasili’s intervention seems to have been benevolent, but having Stalin’s children in their charge made school officials very nervous. Vasili complained to his father:

SEPTEMBER

26 [

NO YEAR

]

Hello Papa,

I live well and go to school and life is fun. I play in my school’s first team of soccer, but each time I go to play there’s a lot of talk about the question that without my father’s permission I can’t play. Write to me whether or not I can play and it will be done as you say.

Vaska Krasny

39

Only Svetlana seemed to have measured the cost to Vasili of his mother’s suicide when he was just eleven. She believed Nadya’s disappearance from their lives completely destroyed her brother. He began drinking at the age of thirteen and, when drunk, often turned his venom against his sister. When his foul language and crude sexual stories became too explicit, Yakov, her half brother, would step in to defend her. She later told several interviewers, “My brother provided me with an early sex education of the dirtiest sort.”

40

She did not elaborate, but it is clear that she kept Vasili at a safe distance. She said she discovered she loved her brother only after he died.

However, she was grateful for one thing. Svetlana was often ill in childhood, but her father refused to send her to the hospital, presumably for security reasons. She remembered long lonely days exiled to her room in the care of nurses and her nanny.

41

But that changed in her adolescence. Saying she was “fat and sickly,” Vasili pushed her into sports. Soon she

joined the ski team and the volleyball team and developed the robust health that would characterize her for the rest of her life.

In 1937 Vasili was finally transferred to Moscow’s Special School No. 2, where he continued to trade on his name, refusing to do his homework, throwing spitballs in class, whistling, singing, and walking out. But at his new school, the administrators tried to coat over his lapses and even allowed him to skip his final exams. The German teacher who tried to give him a failing grade was threatened with dismissal. Even as an exasperated Stalin ordered the keeping of a “secret daybook” on his conduct, higher officials protected him.

42

There is also a much darker rumor attached to his name. Vasili may have “provoked the arrest of the parents of a boy who bested him in an athletic competition.”

43

In 1938, the seventeen-year-old was sent to the Kachinsk Military Aviation School, where Stalin thought he might find the discipline he needed, but again he demanded and received special privileges. Vasili was learning the power of his father’s name, which would eventually prove his undoing.

Meanwhile, Svetlana dutifully brought home her daybook with a record of her academic work and conduct. Over dinner at the Yellow Palace, her father would examine and sign it, as vigilant parents were required to do. He was proud of her. She was a good little girl. Her indoctrination was clear in the words she recorded as a third grader in a testament celebrating the achievements of Nina Groza, the school administrator: “ ‘Under your leadership our school has advanced into the ranks of the best schools of the Soviet Union.’ Svetlana Stalina.”

44

Svetlana had become one of the little “warriors for communism.”

Until she was sixteen, like many of her fellow students, Svetlana remained an idealistic Communist, unreflectingly accepting

Party ideology. In retrospect she would be appalled by how this ideology demanded the censorship of all private thought and led to the mass hypnosis of millions. She called this “the mentality of slaves.” Vasili learned cynically to manipulate the system, which, by its very nature, invited corruption. He understood early that the best way to get ahead was to betray somebody else.