Starcross (10 page)

Authors: Philip Reeve

‘Are you sure, Ferny?’ asked Mr Titfer. His eyes were wide behind those tinted spectacles he wore. ‘You have imported many species of Venusian plant life. Is it possible that a Changeling spore was carried here along with them?’

‘But that is not the worst of it,’ said Mother. ‘They’re young trees, and wrapped about a branch of one of them, I discovered this.’

She held up for our inspection a small bronze tile, from which trailed two ends of a broken chain, as if it had once hung around someone’s neck.

‘Why,’ cried Colonel Quivering, taking it and turning it over in his hands, ‘that was Sir Richard’s! An antique Martian piece! He told me that his wife gave it him, and that he wore it always, beneath his shirt!’

‘Sir Richard?’ exclaimed Myrtle. ‘Sir Richard Burton was at Starcross?’

‘Sir Richard stayed here a few weeks ago,’ said Mr Titfer. ‘A very good, handsome gentleman too,’ said Mrs Spinnaker. ‘He was here with his wife …’

‘A d——d fine young woman,’ said Colonel Quivering. ‘Put me in mind of a lassie I knew when I was stationed on the Equatorial Canal back in ’26 …’ He looked wistful for a moment, then recalled himself and went on, ‘I thought there was something odd about the way the Burtons left us so suddenly, in the middle of the night, without goodbyes.’

‘Mrs Burton said goodbye to me,’ insisted Mr Titfer. ‘She told me that she and Sir Richard had been recalled to London. I remember it distinctly.’

‘I heard shots that night!’ cried Mrs Spinnaker, and, as her husband tried to calm her, ‘No, no, ’Erbert, let me speak! I ’eard them most distinctly! Six pistol shots!’

‘And yet you haven’t mentioned them till now?’ asked Mother.

‘I mentioned them to ’Erbert,’ said the Cockney Nightingale, glaring at her husband. ‘And to Mr Titfer, and both of them said I must have been dreaming, and like a fool I supposed they must be right. But I

did

hear shots! And now Sir Richard has been turned into a tree, and so has his charming wife!’

‘Nobody has been turned into a tree!’ cried poor Professor Ferny, overcoming his natural diffidence and shouting loudly to make himself heard above the worried chatter of the other guests. ‘It is quite impossible that a Changeling Tree should be growing here. I am confident that Mrs Mumby is mistaken.’

‘Then let us go and look,’ said Mr Titfer, starting towards the shoreline, where a rowing boat was drawn up.

‘No, sir!’ warned Colonel Quivering, catching him by the arm. ‘If there is a Changeling Tree out there, you must not risk inhaling its spores.’

‘Neither of the trees is in flower,’ said Mother, ‘so there should be no danger.’

‘Nevertheless, dear Mrs Mumby, we cannot be too cautious. Tell me, Titfer, do we have any respirator masks about the place? Those elephant-nosed contraptions one wears when visiting a gas-moon?’

Mr Titfer shook his head. ‘There is nothing like that on Starcross. No call for ’em.’

Professor Ferny stepped forward. ‘Ladies and gentlemen, allow me to investigate. I am a vegetable already, and Changeling Trees can do me no harm. Wait for me on the terrace, and when I have got to the bottom of this puzzle I shall come and tell you my conclusions.’

And so saying, the noble shrub went rustling down to where the row boat lay, climbed in, and, wrapping a root about the handle of each oar, rowed himself out through the surf towards the island.

We watched him go, and did not look away from the dwindling shape of his boat until the

squeak, squeak, squeak

of turning wheels alerted us to the arrival of Miss Beauregard, who was approaching along the promenade. She had shielded herself from the Sun beneath a vast white parasol, and the wheels of her chair and the skirts of her nurse’s black bombazine dress were brushed with reddish

dust. I remembered what Jack had said about the two of them taking mysterious constitutionals among the unappealing bluffs inland. I could not help wondering, pretty and innocent though she appeared, whether Miss Beauregard was the author of whatever misfortune had overtaken Sir Richard Burton and his wife, and whether it was through her doing that those dreadful trees came to be sprouting upon the island.

But though I backed away from her, and Myrtle positively glared, the young woman in the bath chair seemed not to notice our reactions. She smiled delightfully upon us, and said, ‘You must be the Mumbys; dear Mrs Spinnaker has been telling me all about you. Oh, but why does everybody look so wan? Ignatius, dear, do pray tell me! Whatever has occurred?’

We returned to our bathing machines, which had rolled themselves back up the beach in our absence. ‘Try not to worry, children,’ said Mother, as she climbed the steps to hers, and her smile was so gentle and reassuring that I was almost able to obey her.

As soon as we had dressed we hurried to the dining room

to rejoin the others. There, Mother and Myrtle greeted Grindle and Mr M., tho’ Myrtle still refused to speak to Jack. ‘You should talk to Miss Beauregard instead,’ she told him tartly. ‘I am sure

her

conversation is far more accomplished than mine.’

Miss Beauregard, meanwhile, who had been informed of the discovery upon the island, was busy telling the rest of us about other strokes of ill fortune which had occurred at Starcross. ‘This asteroid is haunted!’ she assured us, in her melodious French accent.

‘Really, Mademoiselle? You astonish me!’ said Mother, who was sat near to her. ‘I simply adore ghost stories, and find that there is nearly always some truth at the bottom of them. Pray tell me what Starcross is supposed to be haunted

by

?’

Miss Beauregard shuddered, as if the room had taken on a sudden chill, and her nurse leaned over and tucked her plaid blankets in around her. ‘It’s simply

haunted

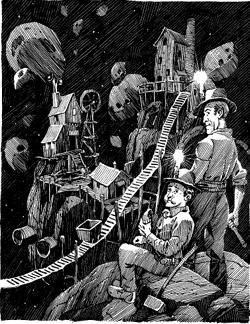

,’ she said. ‘I made a study of it before I came. It seems there was once a mining camp here, owned by some rich English family named Sprigg. They built the railway and had Cornish miners brought in to extract copper and Newtonium, but it was always an unhappy place. The miners suffered from strange dreams, or found themselves of a sudden in other

parts of the asteroid, with not a notion of how they came to be there. Some vanished altogether, and nothing was found of them but their empty clothes.’

‘How horrible!’ exclaimed Mother. ‘But it must have been a lonely spot. Do you think the miners may have imagined those occurrences?’

‘I believe not,’ said Miss Beauregard darkly. ‘Something is wrong here. The way the sea comes and goes. It is not natural.’

‘Sprigg, did you say?’ asked Jack. He looked thoughtful, and I knew why. Sir Launcelot Sprigg was the name of the former Head of the Royal Xenological Institute, the man who had planned to have Jack and his friends dissected.

‘That’s right,’ put in Mr Titfer, overhearing. ‘I … ah …

bought this place from Sir Launcelot a few years back. It wasn’t profitable as a mine. Couldn’t persuade the miners to stay here, superstitious Cornish savages.’

‘And yet you thought rich holidaymakers might be so persuaded,’ mused Mother. ‘How very interesting …’

Just then there came a murmur from those guests nearest to the door, and we saw Professor Ferny enter. The autowaiters who had been trundling among us with glasses and decanters of lemonade and sillery put them down and fetched out a bowl of nutrient broth for the intellectual shrub, who stepped in gratefully and stood a moment in silence, as if savouring the flavour. Naturally, some of our number began to pester him for his opinion on Mother’s Changeling Trees, but he held up a frond for quiet, and they fell silent.

‘Ladies and gentlemen,’ he said, ‘I do not believe you are in any immediate danger.’

There was a sigh of relief at that, but only a brief one, for we could tell by his sombre tone that he had further news to impart, and that it was not good.

‘Those trees which Mrs Mumby and her daughter saw are indeed Changelings,’ he announced. ‘Yet they are not

quite

like the Changeling Trees of Venus. I suspect they are

some form of hybrid. I shall need to make further studies, and I shall require the use of my microscope and Mr Titfer’s library.’

‘Hybrids?’ exclaimed Colonel Quivering. ‘But how did they come here?’

Prof. Ferny rustled his fronds dolefully. ‘When I say “hybrid”, I do not mean a

natural

hybrid. I believe that some cunning person, well versed in botanical science, may have contrived a fast-acting Changeling spore, and inflicted it upon Sir Richard and his wife with malice aforethought.’

‘You mean he is murdered!’ gasped Myrtle.

‘Oh, poor Sir Richard!’ cried Mrs Spinnaker, and promptly fainted into the arms of her husband, who was unable to support her weight and had to call upon Colonel Quivering to help him.

‘Then the same fate may yet befall us all!’ wailed Myrtle.

‘But what scoundrel

would commit such an outrage?’ demanded the colonel, somewhat breathlessly, as he manoeuvred the insensate Cockney Nightingale into an armchair.

‘Please, please!’ called Prof. Ferny, above the hubbub of anxious voices. ‘All may not be lost. While there’s life, there’s hope, and though Sir Richard and Mrs Burton are indisputably trees, they

are

still alive. If a mortal mind devised the spore which caused their transformation, then another mortal mind may yet undo its wicked work. Once I discern the nature of the spore which effected the change, I shall do my utmost to create another which may reverse it.’

‘But, look here, everyone knows the Tree Sickness can’t be cured!’ shouted Mr Spinnaker.