Starcrossed

Authors: Elizabeth C. Bunce

STAY ALIVE

I couldn’t think. My chest hurt from running, and I wasn’t even sure I was in the right place. Tegen had given me directions to a tavern on the river — was this where he’d told me to go, if things went wrong?

It didn’t matter. I had to get off the streets. Behind me, the Oss splashed moonslight over a row of riverside storefronts, bright enough for me to make out the sign of a blue wine bottle and the short flight of stairs down into the alley. Down was shadows and safety. I took it.

You’ll know the place,

he’d said — and there, under my fingers as I felt for the door latch, sparked a tiny, wavering star, carved into the wood so faintly it was nearly invisible. Its odd smoky light faded when I moved my hand away. I tumbled the lock (Tegen had the keys) but had to bang the door open with my hip. I left a smear of blood on the frame as I wrestled it shut again.

Breathing heavily, I took stock. Shelves, barrels, damp stone floor. It was dank and musty, as if the river crept in on rainy days. All good, for me. Must and stuck doors meant ne glect, and ne glect meant nobody was likely to find me here, no matter how busy the tavern got. The only door was the one I came in. A single window at street side, too low for moons light. Except for the occasional passing light of a boat overhead, it should stay dark here all night. Still, I kept to the shadows. Eyes could look into windows as well as out.

How long should I wait?

At least until Tegen came — or Hass showed up with our pay.

Or until the Greenmen got here.

I choked back that thought, my throat tight. I leaned against one of the barrels and peeled back my sleeve, hissing as the cloth pulled away from dried blood. Not as bad as it felt — the point had just grazed my skin. And if I hadn’t blocked that blow, I probably would have lost an eye. Or worse. I took a shaky breath. Bandages. A safe house for thieves should have bandages, right?

The safe house was very much wine cellar and much less hideout, but a bench under the window held spare clothes, at least. I dug out a rumpled green gown like nobs wear, a doxie’s split silk knickers, and a screaming-pink doublet and trunk hose. The hidden mark I’d found on the door meant this place had refuged Sarists during the war, but now it looked more like a hangout for bawds and their bucks. No bandages.

I sacrificed the knickers. Using my teeth, I tore them into ragged strips and tried to concentrate on the work and calm my hammering heartbeat. I uncorked a bottle of wine and went to pour some over the wound, but my hands were jouncing so badly I dumped half the contents on my skirts, dousing the strips of cloth. Cursing every god I knew, I mopped up as much blood as I could, pinning the wet cloth in the crook of my arm to hold it there.

What happened?

I couldn’t slow the images spinning in my mind enough to make sense of them. We’d finished the job; we should have been safe. Tegen had thrown an arm around me and kissed me. I had laughed, the blood rushing in my veins. Hass’s client would have the letters, I’d have fifteen crowns, and Tegen would have me. Everything had gone perfectly.

Until the men in green slammed through the street-side doors and wrenched Tegen off me, a flashing silver blade easing the separation. A bloom of red sprang up on Tegen’s knife — the guard’s blood — a burst of blackness blinded me, and for a moment I couldn’t breathe. And then, cutting through the chaos, Tegen’s voice:

Digger, run!

And I ran. Like I’d never run in my life, crossing what felt like half the city. All the way here, I’d heard their pounding footsteps behind me, but didn’t dare look back. At least one of the Greenmen had to have gotten a good look at me — the one who’d cracked my skull against the wall. Or the one who’d grabbed Tegen.

Panic seized my belly and I fought back nausea.

You got away. You got away.

I repeated the words silently until I no longer felt like gagging. Bruises would heal. But Tegen . . . I swallowed back another wave of panic.

Get hold of yourself if you want to live through the night.

Where was he? He must have gone to Hass first, to deliver the let ters. He’d shake the Greenmen, drop the cargo and get our pay, then circle back here when things were safe. It might take a while. That was why he’d sent me here, to wait for him. I closed my eyes for a moment, but I still saw Tegen, bloody knife in hand, kicking and slashing as I ran away.

I checked the window, although there wasn’t much to be seen from down here. My knee almost buckled under me when I slid off the bar rel, but I couldn’t sit still. The grille on the window made the room feel like a cell, and the smell of my own blood was starting to make me light-headed.

Food. I needed food, and sleep, and a plan. I probably also needed medical attention, but it wasn’t like I ever had access to that. Food could wait; I’d spent more than one night hungry — though not lately — another wouldn’t kill me. Dry clothes, however . . .

The guards were looking for a girl in black wool. As a boy I’d be less conspicuous — but

not

in that ridiculous pink costume. The green then, wrinkled as it was. It was safest, anyway. Guards were less likely to stop someone in green to check papers. I clawed the pins from my hair with one hand and twisted my laces free with the other, but as the kirtle loosened, I felt the crinkle of paper between the wool and my corset.

Everything in me sank again. Tegen must have slipped Chavel’s letters into my bodice when he kissed me. The pins scattered to the floor as I dipped a hand into my dress to pull the packet of letters free.

They were spotted with blood.

Tegen wasn’t coming.

I stood there, half undone, staring at the folded papers in my trembling fingers. I hadn’t let myself believe he wouldn’t get away. He was

Tegen.

But my bruised knee, my cracked skull, and my bloody arm told the truth. If Tegen hadn’t stabbed that guard — stupid, reckless, deadly thing to do — the Greenmen would just have arrested two thieves. Searched us, branded us, maybe even let us go, if Hass coughed up our bounty. But instead they got one heretic: It was a sin to strike the servants of the Goddess, even her pox-ridden temple guards. And heresy was the only crime those men in green really cared about.

I wanted to charge straight back there and drag him away, but at the thought of those hands on him — on

me

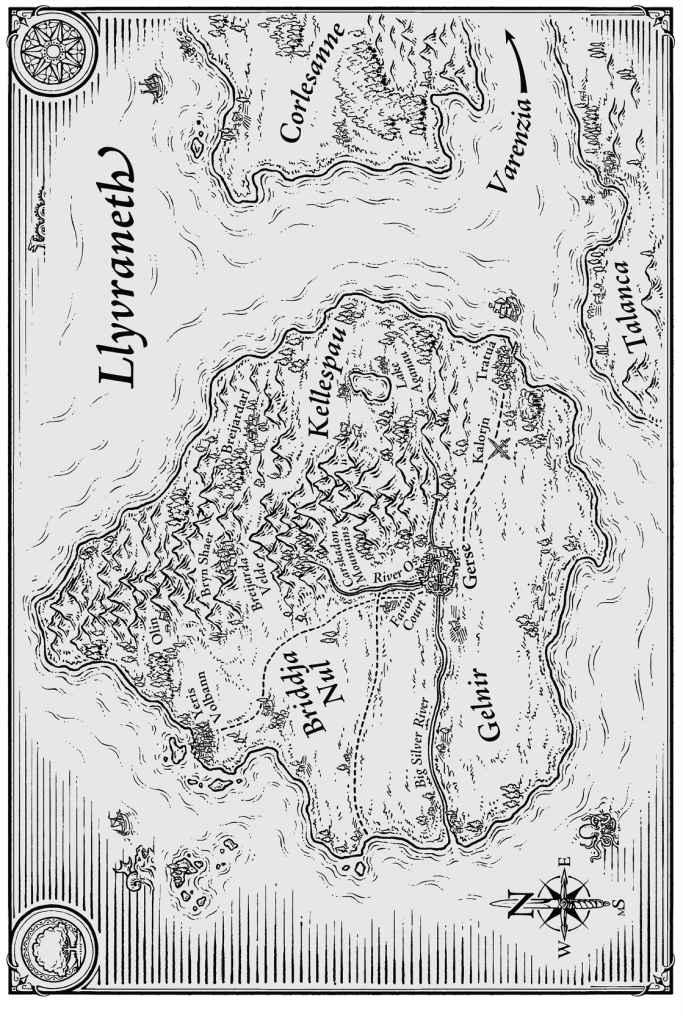

again — I sank to the floor. I knew what every thief knew, what every citizen of Gerse knew, these days: Nobody gets away from Greenmen.

I sat there all night, even as my leg stiffened up, even as I knew I had to get out of there and move. A safe house was temporary; someone was bound to come down here eventually, and I had the evidence of my crime all over me.

I should get rid of the letters. I should get them to Hass, get paid for them.

But Hass hadn’t been there. He hadn’t seen the men in green melt out of the woodwork and seize Tegen —

A sickening idea stopped that thought cold.

Had he set us up?

I didn’t know what to do next. This was Tegen’s job, and Hass was Tegen’s contact; I’d just been along to make sure we lifted the right documents. Tegen didn’t read — he couldn’t tell one language from another, couldn’t distinguish a symbol that might be charmed from something commonplace. I possessed that unique skill, and it had made me a valuable partner.

Valuable enough to trust with the prize?

I turned the letters over, rubbed their folded edges, but stopped short of opening them. They were written in Corles, a language I could recognize but not read. Hass had given specific instructions about what to look for — the language, the mark of the king’s private secretary. There was nothing . . . special about these papers. They lay cold and dead and ordinary in my hands.