Starfish (6 page)

A

N

I

CY

R

IVER

⢠O

LD

M

AN

M

AKES

P

EOPLE

⢠L

EAVING THE

R

ESERVATION

⢠L

IONEL'S

S

ECOND

D

REAM

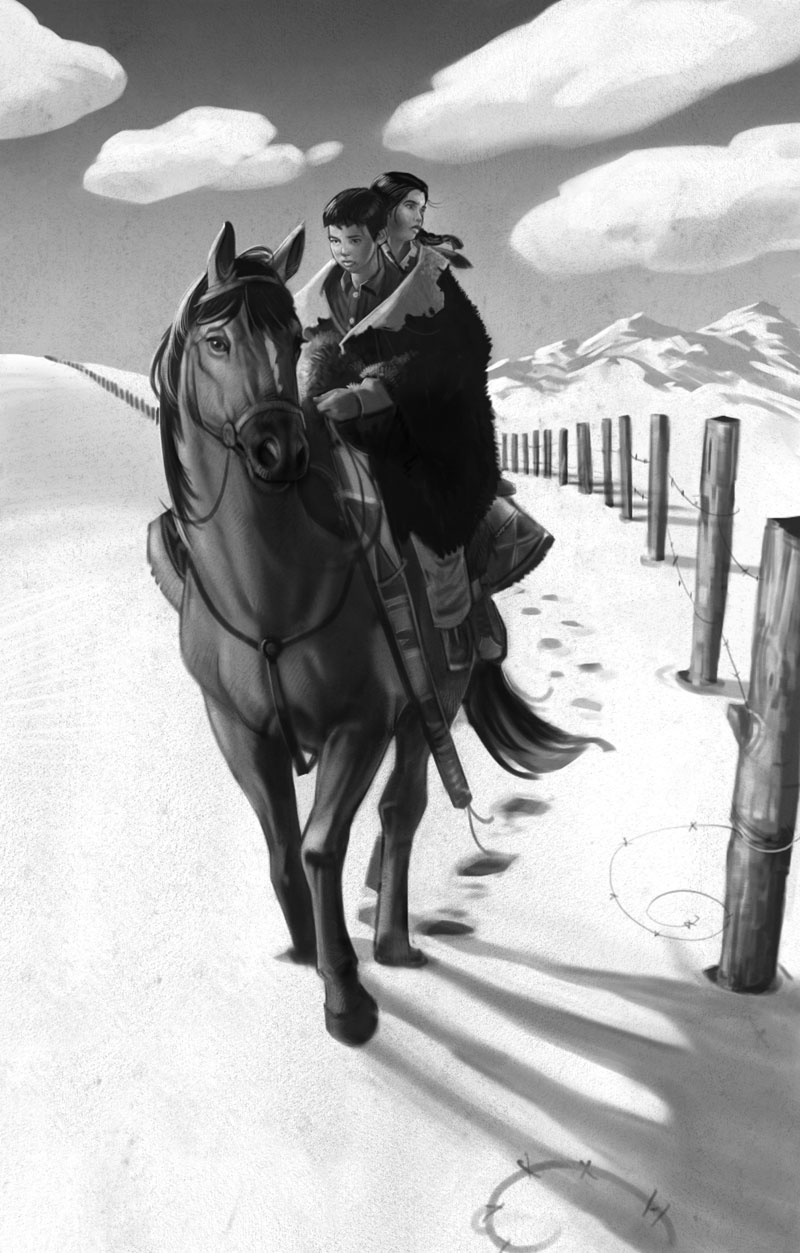

ULYSSES STRUGGLED

as they navigated their way along the river's icy banks. The riverbed consisted of large loose rocks that caused the horse to slip and stumble, and Beatrice and Lionel had to stop twice to retie the load.

As they rode, Beatrice recounted what their grandfather had told her during the night after Lionel had fallen asleep. She told Lionel that a long time ago, their grandfather had been made to join the government's army, and that he had been taken by a large boat across a great body of water where they fought other men who spoke different languages. Many men died, including two of Grandpa's older brothers.

They gave Grandpa a medal like the ones the captain wore, but Grandpa didn't want it. He thought that it was given to him because he had somehow survived while so many others were killed. Grandpa buried the medal for his brothers on the banks of the river.

As they rode, the mountains got closer and closer, and Lionel thought that they might reach them that very afternoon, but he was wrong.

Midday, as Grandpa had said, a stream joined the river. Beatrice led Ulysses up onto a sandy snow-covered bank of the tributary, where they stopped to rest and eat. They ate cold elk meat and some of the hardtack biscuits that their grandfather had packed for them, and then were back on their way.

As they rode through the afternoon, Beatrice told Lionel more about Napi the old Man, as their grandfather had explained it to her.

“Grandpa said that after the old Man created the world, he realized that he was lonely and that he needed someone to talk to. So one day the old Man decided that it was time to create peopleâus, I reckon. The old Man made two figures of clay, one of a woman and one of her son. The old Man buried 'em in the ground by the river and left 'em.”

“Why would he leave them?”

Beatrice stared at him blankly, then continued, “The old Man returned on the second day and noticed that the clay figures had changed but still didn't look like people. on the third day, he came back and once again, although they were different, they still weren't people. on the fourth day, Grandpa said that the old Man returned and unburied 'em. He told the clay people to get up and walk; and they did⦔

“They did?” Lionel asked, turning to look at Beatrice.

“Yup. 'Cause now they were people.”

“How did that happen?”

“I don't know,” Beatrice answered. “Grandpa didn't say.”

Lionel surveyed the vast landscape and the approaching foothills of the mountains. The land slowly changed as Beatrice spoke. The rolling plains gave way to foothills. The foothills grew bigger and seemed to sprout clumps of trees, mostly pine, aspen, and birch.

“Grandpa said that the old Man led the clay people to the water at the edge of the river where he told them, âI am Napi. Napi the old Man.' But the old Man knew that like him, the people would be lonely, so he took more clay and blew onto it. The clay became more men and women, but now the old Man figured that his people were hungry, and they didn't have no clothes. So he took more clay and made the buffalo. He told the clay people that the buffalo and the other animals were their food, and told them to hunt 'em.”

Lionel thought about Napi the old Man building the mountains and telling the plants where to grow. Then he thought about the clay people and the buffalo.

Sometime late that afternoon the children reached the dilapidated remnants of a barbed wire fence that Beatrice, although unsure, figured to be the boundary of their reservation. Neither Lionel nor Beatrice had ever left the reservation. Lionel was not sure if the same could be said about Ulysses.

They paused before the fence and marveled as it snaked north and south as far as their eyes could see. Lionel looked across the fence and thought that besides the proximity of the looming mountains, the rough terrain looked remarkably similar to the land that they had traveled for the majority of the afternoon.

Beatrice seemed nervous and turned Ulysses in a circle, surveying the snow-covered desolation that surrounded them.

“You think you're ready?” Beatrice asked, breaking the uneasy feeling that the immense border brought.

“I guess” was all Lionel could think to say.

“We may never be coming back, you know. we may never be allowed back,” Beatrice added, and then dug in her heels, asking Ulysses to proceed.

The horse stepped forward, and with that step, completely alone and without permission or legal permit, the children rode through a gaping hole in the fence, leaving the reservation and all that they had ever known.

It grew dark, and Beatrice led Ulysses toward a small rock outcrop that jutted up from the bank. That night they slept off the reservation for the first time in their lives, wrapped in the buffalo robe in the shallow of a small cave at the foot of the mountains. They roasted the elk on sticks and ate; then Beatrice lay down and did not move until morning. Lionel wondered how much she had slept the night before.

Lionel fell asleep listening to the crackling embers of the small fire they had built. He dreamed that he stood on the side of a great river. There, he saw the bighorn sheep, the antelope, and then the buffalo rise from the earth and run across the river and out onto the open rolling plains. Lionel heard a low rumble from the earth, and Beatrice and their grandfather rose from the banks. They also crossed the river and followed the buffalo and the other animals. In his dream, Lionel tried to follow, but could not make it across the great river. The river's opposite bank was moving farther away, moving to well beyond the distant horizon.

B

EATRICE

G

ROWS

W

EARY

⢠C

OLD AND

M

ORE

S

NOW

⢠I

NTO THE

M

OUNTAINS

WHEN LIONEL

woke, Beatrice was still asleep. He lay curled in the buffalo robe next to his sister and thought about the clay people and if they grew to become the Blackfeet. He wondered if the people Napi the old Man created were the same as the first two people the Brothers and priests at the boarding school had told him were the first created. Their first man had also been created from the earth: the woman from a rib. Lionel concluded that they must have been the first two white people, and that the clay people Grandpa had told Beatrice about were the first of the Blackfeet.

Lionel got up, stoked the fire for Beatrice, and led Ulysses down to the stream to drink. A distant sun stretched across the dull morning sky. Lionel turned with the first light and looked toward the great mountains and the black menacing clouds that clung to their tops. He returned to their camp and found Beatrice rolling up the buffalo robe. She seemed detached and tired, so Lionel lifted the bundles and tied them to Ulysses the way his grandfather had showed him, without speaking.

They ate cold elk and were soon on their way, riding well into the afternoon. They continued to follow the stream, pushing Ulysses up the increasingly rough and rocky terrain and under the long stretches of trees that seemed to touch the sky. They came to several forks in the stream but always kept to the right, fighting the deep banks of snow that lay on either side.

Lionel noticed that the stream grew smaller the higher they traveled, and eventually more difficult to follow. By late afternoon, the only evidence that the river was still with them was the low gurgle of water that struggled unseen under its heavy coat of winter ice and snow.

Sometime late that afternoon, it began to snow again. The snow covered the trees and caused their branches to bend and drop their burden onto the children and the great horse as they passed. Lionel grew cold as the day wore on, and Beatrice pulled the robe tighter. They drifted in and out of sleep, but Beatrice always woke in time to keep Ulysses going or to navigate the river's increasingly treacherous banks.

It soon became dark, but Ulysses continued to climb. occasionally he would throw back his head or nip gently at the children's feet to wake them, as if he could tell when the children were slipping while they slept. Beatrice began to cough sometime in the night, and Lionel thought about when she had been sick. The captain had told Lionel that it was possible that Beatrice might never be able to leave the infirmary. But Beatrice had showed them. Beatrice always showed them.

The snow stopped falling sometime near morning. Lionel woke and looked above them at the clearing clouds and the ink black night with its sparkling array of stars now clustered overhead. Beatrice continued coughing in her sleep, so Lionel stayed awake, taking in the landscape that surrounded them. Light soon filled the morning sky, revealing a world that was entirely new to him. Lionel had grown accustomed to the wide-open space of the boarding school and the reservation. Here in the mountains, he couldn't see more than a hundred paces before the dense snow-covered trees or large white-dolloped boulders blocked his view. They continued on, and soon Lionel fell back asleep.

A C

ROOKED

L

ODGE

⢠L

IONEL

T

AKES

C

ARE OF

B

EATRICE

⢠“W

E

M

ADE

I

T”

LIONEL FOUND

himself staring into the tangled mess of Ulysses's tousled mane. He looked around, trying to fully wake up and get his bearings. He discovered he was in a small, dilapidated, open-sided barn. Ulysses was tearing at an empty burlap grain sack, attempting to get the last of its remnants into his big mouth. Beatrice was still asleep.

Lionel rubbed his eyes and wondered for a moment if it hadn't all been some kind of dream, and he was actually back at the school about to be in trouble for sitting on Ulysses's back. His body ached, and he was cold.

He crawled from beneath the buffalo robe, carefully, so as not to wake his sister, then dropped to the frozen dirt of the stable and collapsed. Lionel's legs and feet still hadn't woken up. He sat for a minute and saw that Ulysses's deep tracks followed the stream across a small, open, tree-lined meadow. Mountains loomed above them on all sides.

Lionel looked up at his sister. She slumped forward with her arms sprawled across the horse's neck. Lionel had never seen her sleep this much and decided to leave her while he investigated their latest stop.

He left the shelter of the stable and stepped out into the deep snow of the meadow. It came up to his waist, and after only a few steps he had to stop to catch his breath. He had never seen this much snow in his life. Though the surroundings seemed peaceful, he could not shake the feeling that they were not alone. Something was watching them.

Lionel scanned the tree line to find that a large raven, so black it looked almost blue, was sitting opposite him on a spindly winter branch, calmly observing the small valley's newest inhabitants. “Hello,” Lionel called, but the bird just spread its large wings and took to the air.

Lionel watched the raven fly its way to the tops of the nearby trees, but as he did, he caught something else out of the corner of his eye. There, at the far corner of the meadow, nestled back and surrounded by a small stand of pine, birch, and aspen, sat a long, lonely log cabin. Despite its size, Lionel almost missed it, as the building seemed either to have sprung from the earth or to be in the process of being taken back into it.

The chimney stood like a stone giant that had lost its balance, fallen, and then leaned on the lodge, pushing the entire structure to one side and collapsing the roof on the farthest end. The remaining roof was covered by four feet of snow. Lionel thought that it looked like frosting on top of a cake or, more accurately, the frosting on a cake that someone had dropped.

Lionel returned to the stable. Beatrice was still sleeping, so he took Ulysses by his rawhide harness and led them toward the slumping building. Even the doorframe leaned to one side.

He left Beatrice with the horse and pushed open the heavy, crooked door. The door creaked on its leather hinges, revealing, once he was inside, that over half of the building still seemed to be perfectly intact. The other side fell off in a maze of cracked timber and broken glass, but the rubble passed for a fourth wall.

Light from outside shone through the dingy windows, and Lionel already felt a little warmer stepping inside and out of the wind that came down off the mountains and across the small meadow. He made his way around various bits of debris and toward the center of the enormous fireplace. You could have put four of Grandpa's fireplaces into this one, Lionel thought. A box of kindling stood next to the giant stones, and in no time Lionel had a small fire going that was dwarfed by its immense surroundings. Lionel decided that if he could do it, he should bring both Ulysses and Beatrice into the house. How else would he be able to carry his sleeping sister?

It took some coaxing, but he convinced Ulysses to lower his head, and led them both into the cavernous warmth that his little fire and the fallen lodge provided. Lionel did his best to wrap Beatrice in the buffalo robe and lower her gently in front of the fire, but despite his best effort she still tumbled off the horse's back.

Beatrice sat up and looked around. “We made it,” she said, and drifted back to sleep. Though it was frigid out, Lionel thought that Beatrice's face felt hot. But she was shivering, so he got her some water, wrapped the buffalo robe tight, and turned back to stoke the fire.

Lionel led Ulysses to the far side of the lodge, figuring that the horse could sleep there for the night. Ulysses snorted and poked at the cabin's crumbled remains as Lionel did his best to unload their supplies. He located their tight bundles of food, then sat down by the fire next to Beatrice and ate some of the dried meat. He was tired and cold, but as Beatrice said, they had made it.