Stiff (26 page)

Authors: Mary Roach

Interestingly, White, a devout Catholic, is a member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, some seventy-eight well-known scientific minds (and their bodies) who fly to Vatican City every two years to keep the Pope up to date on scientific matters of special interest to the church: stem cell research, cloning, euthanasia, even life on other planets. In one sense, this is an odd place for White, given that Catholicism preaches that the soul occupies the whole body, not just the brain. The subject came up during one of White's meetings with the Holy Father. "I said to him,

'Well, Your Holiness, I seriously have to consider that the human spirit or soul is physically located in the brain.' The Pope looked very strained and did not answer." White stops and looks down at his coffee mug, as though perhaps regretting his candor that day.

"The Pope always looks a little strained," I point out helpfully. "I mean, with his health and all." I wonder aloud whether the Pope might be a good candidate for total body transplant. "God knows the Vatican's got the money…." White throws me a look. The look says it might not be a good idea to tell White about my collection of news photographs of the Pope having trouble with his vestments. It says I'm a

petit bouchon fécal

.

White would very much like to see the church change its definition of death from "the moment the soul leaves the body" to "the moment the soul leaves the brain," especially given that Catholicism accepts both the concept of brain death and the practice of organ transplantation. But the Holy See, like White's transplanted monkey heads, has remained pugnacious in its attitude.

No matter how far the science of whole body transplantation advances, White or anyone else who chooses to cut the head off a beating-heart cadaver and screw a different one onto it faces a significant hurdle in the form of donor consent. A single organ removed from a body becomes impersonal, identity-neutral. The humanitarian benefits of its donation outweigh the emotional discomfort surrounding its removal—for most of us, anyway. Body transplants are another story. Will people or their families ever give an entire, intact body away to improve the health of a stranger?

They might. It has happened before. Though these particular curative dead bodies never found their way to the operating room. They were more of an apothecary item: topically applied, distilled into a tincture, swallowed or eaten. Whole human bodies—as well as bits and pieces of them—were for centuries a mainstay in the pharmacopoeias of Europe and Asia. Some people actually volunteered for the job. If elderly men in twelfth-century Arabia were willing to donate themselves to become

"human mummy confection" (see recipe, next chapter), then it's not hard to imagine that a man might volunteer to be someone else's transplanted body. Okay, it's maybe a little hard.

Footnotes:

[

1]

When he tired of moving organs and heads around, Demikhov moved on to entire dog halves. His book details an operation in which two dogs were split at the diaphragm, their upper and lower halves swapped, and their arteries grafted back together. He explained that this might be less time-consuming than transplanting two or three individual organs.

Given that the patients spinal nerves, once severed, could not be reconnected and the lower half of the body would be paralyzed, the procedure failed to generate much enthusiasm.

[

2]

Legendary for skewering heads of state, from Kissinger to Arafat ("a man born to irritate"). Fallaci stuck it to White by making up a name for the anonymous lab monkey whose brain she had watched being isolated and for writing things like this: "While [the brain removal and hookup]

happened, no one paid any attention to Libby's body, which was lying lifeless. Professor White might have fed it, too, with blood, and made it survive without a head. But Professor White didn't choose to, and so the body lay there, forgotten."

10

Eat Me

Medicinal cannibalism and the case of the human dumplings

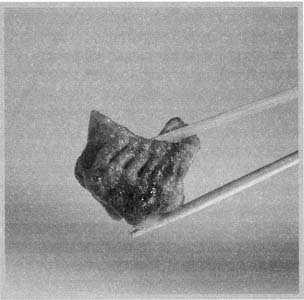

In the grand bazaars of twelfth-century Arabia, it was occasionally possible, if you knew where to look and you had a lot of cash and a tote bag you didn't care about, to procure an item known as mellified man.

The verb "to mellify" comes from the Latin for honey,

mel

. Mellified man was dead human remains steeped in honey. Its other name was "human mummy confection," though this is misleading, for, unlike other honey-steeped Middle Eastern confections, this one did not get served for dessert. One administered it topically and, I am sorry to say, orally as medicine.

The preparation represented an extraordinary effort, both on the part of the confectioners and, more notably, on the part of the ingredients:

…In Arabia there are men 70 to 80 years old

who are willing to give their bodies to save

others. The subject does not eat food, he only

bathes and partakes of honey. After a month he

only excretes honey (the urine and feces are

entirely honey) and death follows. His fellow

men place him in a stone coffin full of honey

in which he macerates. The date is put upon

the coffin giving the year and month. After a

hundred years the seals are removed. A

confection is formed which is used for the

treatment of broken and wounded limbs. A small

amount taken internally will immediately cure

the complaint.

The above recipe appears in the

Chinese Materia Medica

, a 1597

compendium of medicinal plants and animals compiled by the great naturalist Li Shih-chen. Li is careful to point out that he does not know for certain whether the mellified man story is true. This is less comforting than it sounds, for it means that when Li Shih-chen does

not

make a point of questioning the veracity of a

Materia Medica

entry, he feels certain that it is true. This tells us that the following were almost certainly used as medicine in sixteenth-century China: human dandruff ("best taken from a fat man"), human knee dirt, human ear wax, human perspiration, old drumskins ("ashed and applied to the penis for difficult urination"), "the juice squeezed out of pig's feces," and "dirt from the proximal end of a donkey's tail."

The medicinal use of mummified—though not usually mellified—

humans is well documented in chemistry books of sixteenth-, seventeenth-, and eighteenth-century Europe, but nowhere outside Arabia were the corpses volunteers. The most sought-after mummies were said to be those of caravan members overcome by sandstorms in the Libyan desert. "This sudden suffocation doth concentrate the spirits in all the parts by reason of the fear and sudden surprisal which seizes on the travellers," wrote Nicolas Le Fèvre, author of

A Compleat Body of

Chymistry

. (Sudden death also lessened the likelihood that the body was diseased.) Others claimed the mummy's medicinal properties derived from Dead Sea bitumen, a pitchlike substance which the Egyptians were thought, at the time, to have used as an embalming agent.

Needless to say, the real deal out of Libya was scarce. Le Fèvre offered a recipe for home-brewed mummy elixir using the remains of "a young, lusty man" (other writers further specified that the youth be a redhead).

The requisite surprisal was to have been supplied by suffocation, hanging, or impalement. A recipe was provided for drying, smoking, and blending (one to three grains of mummy in a mixture of viper's flesh and spirit of wine) the flesh, but Le Fèvre offered no hint of how or where to procure it, short of suffocating or impaling the young carrot-top oneself.

There was for a time a trade in fake mummies being sold by Jews in Alexandria. They had apparently started out selling authentic mummies raided from crypts, prompting the author C. J. S. Thompson in

The

Mystery and Art of the Apothecary

to observe that "the Jew eventually had his revenge on his ancient oppressors." When stocks of real mummies wore thin, the traders began concocting fakes. Pierre Pomet, private druggist to King Louis XIV, wrote in the 1737 edition of

A Compleat

History of Druggs

that his colleague Guy de la Fontaine had traveled to Alexandria to "have ocular demonstration of what he had heard so much of" and found, in one man's shop, all manner of diseased and decayed bodies being doctored with pitch, wrapped in bandages, and dried in ovens. So common was this black market trade that pharmaceutical authorities like Pomet offered tips for prospective mummy shoppers:

"Choose what is of a fine shining black, not full of bones and dirt, of good smell and which being burnt does not stink of pitch." A. C.Wootton, in his 1910

Chronicles of Pharmacy

, writes that celebrated French surgeon and author Ambroise Paré claimed ersatz mummy was being made right in Paris, from desiccated corpses stolen from the gibbets under cover of night. Paré hastened to add that he never prescribed it. From what I can tell he was in the minority. Pomet wrote that he stocked it in his apothecary (though he averred that "its greatest use is for catching fish").

C. J. S. Thompson, whose book was published in 1929, claimed that human mummy could still be found at that time in the drug-bazaars of the Near East.

Mummy elixir was a rather striking example of the cure being worse than the complaint. Though it was prescribed for conditions ranging from palsy to vertigo, by far its most common use was as a treatment for contusions and preventing coagulation of blood: People were swallowing decayed human cadaver for the treatment of

bruises

. Seventeenth-century druggist Johann Becher, quoted in Wootton, maintained that it was "very beneficial in flatulency" (which, if he meant as a causative agent, I do not doubt). Other examples of human-sourced pharmaceuticals surely causing more distress than they relieved include strips of cadaver skin tied around the calves to prevent cramping, "old liquified placenta" to

"quieten a patient whose hair stands up without cause" (I'm quoting Li Shih-chen on this one and the next),"clear liquid feces" for worms ("the smell will induce insects to crawl out of any of the body orifices and relieve irritation"), fresh blood injected into the face for eczema (popular in France at the time Thompson was writing), gallstone for hiccoughs, tartar of human teeth for wasp bite, tincture of human navel for sore throat, and the spittle of a woman applied to the eyes for ophthalmia.

(The ancient Romans, Jews, and Chinese were all saliva enthusiasts, though as far as I can tell you couldn't use your own. Treatments would specify the type of spittle required: woman spittle, newborn man-child spittle, even Imperial Saliva, Roman emperors apparently contributing to a community spittoon for the welfare of the people. Most physicians delivered the substance by eyedropper, or prescribed it as a sort of tincture, although in Li Shih-chen's day, for cases of "nightmare due to attack by devils," the unfortunate sufferer was treated by "quietly spitting into the face.")

Even in cases of serious illness, the patient was sometimes better off ignoring the doctor's prescription. According to the

Chinese Materia

Medica

, diabetics were to be treated with "a cupful of urine from a public latrine." (Anticipating resistance, the text instructs that the heinous drink be "given secretly") Another example comes from Nicholas Lemery, chemist and member of the Royal Academy of Sciences, who wrote that anthrax and plague could be treated with human excrement. Lemery did not take credit for the discovery, citing instead, in his

A Course of

Chymistry

, a German named Homberg who in 1710 delivered

before the

Royal Academy

a talk on the method of extracting "an admirable phosphorus from a man's excrements, which he found out after much application and pains"; Lemery reported the method in his book ("Take four ounces of humane Excrement newly made, of ordinary consistency…"). Homberg's fecal phosphorus was said to actually glow, an ocular demonstration of which I would give my eyeteeth (useful for the treatment for malaria, breast abscess, and eruptive smallpox) to see.

Homberg may have been the first to make it glow, but he wasn't the first to prescribe it. The medical use of human feces had been around since Pliny's day. The

Chinese Materia Medica

prescribes it not only in liquid, ash, and soup form—for everything from epidemic fevers to the treatment of children's genital sores—but also in a "roasted" version. The thinking went that dung is essentially, in the case of the human variety,[

1]

bread and meat reduced to their simplest elements and thereby "rendered fit for the exercise of their virtues," to quote A. C.

Wootton.

Not all cadaveric medicines were sold by professional druggists. The Colosseum featured occasional backstage concessions of blood from freshly slain gladiators, which was thought to cure epilepsy,[

2]

but only if taken before it had cooled. In eighteenth-century Germany and France, executioners padded their pockets by collecting the blood that flowed from the necks of guillotined criminals; by this time blood was being prescribed not only for epilepsy, but for gout and dropsy.[

3]

As with mummy elixir, it was believed that for human blood to be curative it must come from a man who had died in a state of youth and vitality, not someone who had wasted away from disease; executed criminals fit the bill nicely. It was when the prescription called for bathing in the blood of infants, or the blood of virgins, that things began to turn ugly. The disease in question was most often leprosy, and the dosage was measured out in bathtubs rather than eyedroppers. When leprosy fell upon the princes of Egypt, wrote Pliny, "woe to the people, for in the bathing chambers, tubs were prepared, with human blood for the cure of it."