Read Storming the Eagle's Nest Online

Authors: Jim Ring

Storming the Eagle's Nest (7 page)

Once France had actually fallen, morale in Switzerland became ever more critical. Defeatism was commonplace both in the general population and the army. In these circumstances Guisan decided to stage a rally for the benefit of his officers, their subordinates and – ultimately – the Swiss people. He chose a location of great symbolic significance for the Swiss: the Rütli meadow on the eastern shore of Lake Lucerne. Here, in 1291, tradition placed the foundation of Switzerland on the occasion of the forging of the alliance between the cantons of Uri, Schwyz and Unterwalden. On 25 July 1940 there was to be a repeat performance. There the General mustered his Chiefs of Staff and the entire 650-strong officer corps. Grouped in a semicircle facing the silver lake in which were reflected the glories of the surrounding peaks of Mount Pilatus and Mount Rigi, Guisan told his officers, ‘We are at a turning point of our history. The survival of Switzerland is at stake.’

19

Excerpts from the speech were printed and broadcast on that day, and it was announced that the Redoubt was to be manned by eight infantry divisions and three mountain brigades.

After the Rütli speech Guisan toured the whole country, becoming just the sort of national hero that politicians deplore: a Nelson, Wellington or a Bonaparte. As Swiss historians remark, the battle had begun between Guisan and the political classes for the Swiss soul. Through the blissfully hot summer of 1940, as the fate of Switzerland hung in the balance, the General became the human embodiment of the resistance spirit, the Widerstandsgeist.

Six days after the Rütli rally, on 31 July 1940, Hitler once again gathered his warlords at the Berghof. It was just a fortnight after

their last meeting. By this time they were used to the tiresome journey from Berlin: either a flight from the capital’s Tempelhof airfield to Salzburg, or an eight-hour train journey via Munich. Raeder was present once again to report on the developing plans for invading England, with the army leaders – Brauchitsch, Halder, Keitel and Jodl – to advise on the land war in all its aspects. Army Commander-in-Chief Generalfeldmarschall Walther von Brauchitsch was earmarked as Churchill’s successor, the man who would take the Prime Minister’s seat in Downing Street, though probably not in the House of Commons.

Invasion was certainly the order of the day, with plans afoot to invade Germany’s new ally, the Soviet Union, as well as England and Switzerland. On Operation Sea Lion, Raeder was pessimistic about the weather prospects for the early autumn, the lack of German shipping – which could restrict the landings to the fairly well-defended coast between Dover and Eastbourne – and the efficacy of the Luftwaffe. In these circumstances he proposed May 1941 as the best time for the adventure. Hitler, mindful of the time this would allow Britain to re-equip Gort’s Expeditionary Force evacuated from Dunkirk, was in more of a hurry. In the end the conference agreed to aim for 15 September 1940, subject to the efforts of Hermann Göring’s Luftwaffe and the success of Unternehmen Adlerangriffe. On 1 August Hitler issued Directive No. 17. This required preparations for this invasion to be completed by 15 September 1940, with the invasion itself to be set for a day between 19 and 26 September.

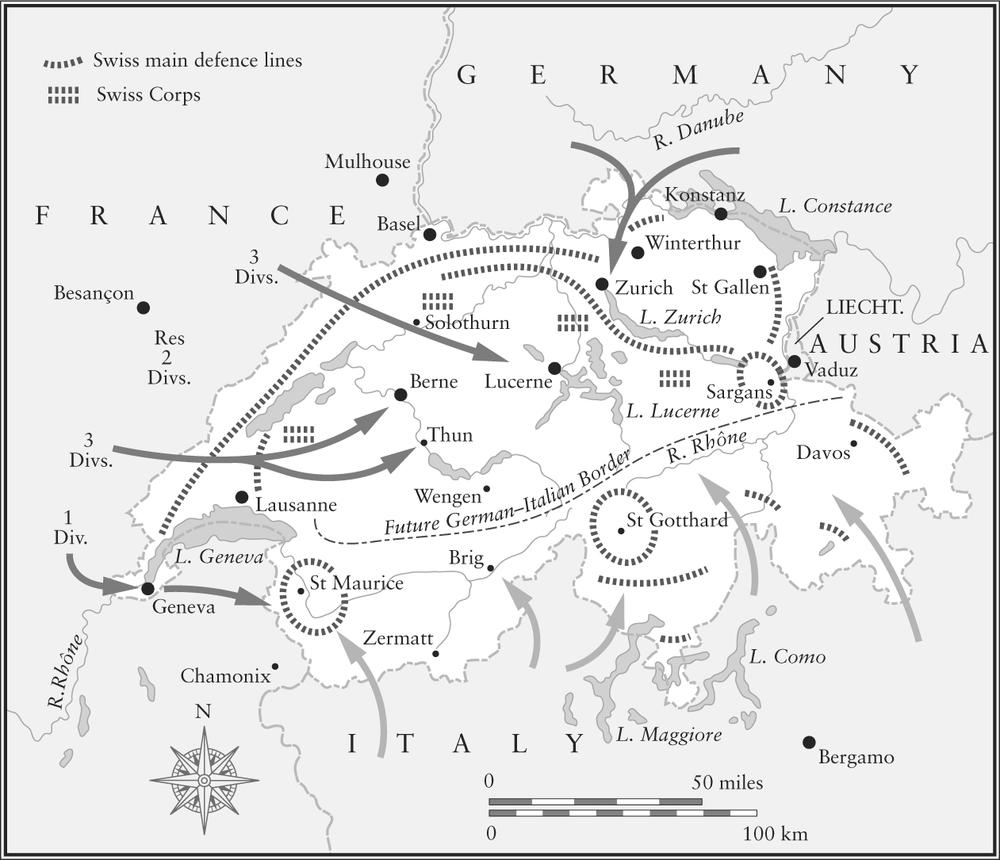

The first of August 1940 – the date of the Berghof meeting – was also the Swiss National Day, the 649th anniversary of the Rütli accord in 1291. It was marked by thousands of beacons set blazing on the country’s Alpine peaks, so sending a message of defiance to would-be invaders. This was timely, for the OKW had been reviewing its plans for invading Switzerland; Captain Otto von Menges had been busy once again. On 12 August 1940 his staff submitted a revised plan to Generaloberst Franz Halder. The Chief of Staff was himself busy overseeing the first-draft plans for the invasion of the Soviet Union. Menges proposed a simultaneous

attack on Switzerland from both Germany and occupied France. Halder thought a feint, much like that carried out in May by the Seventh Army, would be more effective. An infantry attack in the Jura would draw in the Swiss army, and then a second attack in the south would attempt to cut off the army’s line of retreat to the Alps. Halder allotted eleven divisions for the attack, some 150,000 men. Yet when he came to undertake a reconnaissance of the Swiss operation by driving along the French and German sections of the border, he had second thoughts. ‘The Jura frontier offers no favourable base for an attack. Switzerland rises, in successive waves of wood-covered terrain, across the axis of an attack. The crossing points on the river Doubs and the border are few; the Swiss frontier position is strong.’

20

Captain von Menges’s plan for the invasion of Switzerland

In any case, Operation Sea Lion was proving a distraction. In the absence of what the Führer himself called ‘complete air superiority’, on 14 September 1940 Raeder, Halder and the

Führer had been obliged to meet again – for once in the Berlin Chancellery rather than the Berghof. Hitler conceded, ‘The enemy recovers again and again.’

21

Three days later he postponed the invasion. The German Naval War Diary drily records, ‘The enemy Air Force is by no means defeated.’

22

Reluctantly, Hitler ordered the dispersal of the shipping gathered in the Channel ports to transport the invading Heeresgruppe A and B (Army Groups A and B). They had been subjected to persistent RAF attacks. On 4 October, Hitler and Mussolini again met at the Brenner Pass. Ciano was again in attendance, the Italian foreign minister noting, ‘There is no longer any talk of landing into the British Isles’. After his humiliation of three months earlier over the fiasco in the Alpes-Maritimes, this put Mussolini into a transport of delight. Ciano commented, ‘Rarely have I seen the Duce in such good humour as after the Brenner Pass today.’

23

*

On 19 October 1940, Guisan announced that home defence soldiers aged between forty-two and sixty were being recalled to relieve younger troops who had been on duty since the war began. This was tacit acceptance that, with winter drawing in, the threat of invasion was over for the year. After the breathtaking successes of the early summer, Hitler had met with failure over the Channel and frustration in the Alps. The German historian Joachim Fest commented, ‘In Churchill Hitler found something more than an antagonist. To a panic-stricken Europe the German dictator had appeared almost like invincible fate. Churchill reduced him to a conquerable power.’

24

As many reflected, it was a strange, paradoxical, quixotic turn of events. Hitler had written to Mussolini that ‘in that country at present it is not reason that rules’.

Henri Guisan in Switzerland had taken a similar line, albeit in a lower key. ‘It’s not their war,’ reflected Shirer. ‘But they’re ready to fight to defend their way of life. I asked a fat businessman in my [train] compartment whether he wouldn’t prefer peace at any price … “Not the kind of peace that Hitler offers,” he said. “Or the kind of peace we’ve been having the last five years.”’

25

In Zermatt, shortly after the Fall of France, the mountain guide Bernard Biner had been sheltering in the Schönbühl Hut on the old trade route between the Swiss resort and Sion in the Rhône valley. Hearing a tremendous roar, he rushed outside, thinking the chimney was on fire. He saw, low over the Theodule Pass, a lone British bomber heading south towards Milan. ‘I knew then that England would fight back. I was happier than I’d been for weeks.’

26

1

. Churchill,

Second World War, Volume II.

2

. Shirer,

Rise and Fall.

3

. Shirer,

Rise and Fall.

4

. www.winstonchurchill.org/

learnspeeches/speeches-of-

winstonchurchill

/

128-we-shall-fight-on-the-beaches.

5

. Shirer,

Rise and Fall.

6

.

Strand Magazine,

1894.

7

. Alan Morris Schom,

A Survey of Nazi and Pro-Nazi Groups in Switzerland: 1930–1945

(Los Angeles: Simon Wiesenthal Center, 1998).

8

. Shirer,

Berlin Diary.

9

. Stephen P. Halbrook,

The Swiss and the Nazis: How the Alpine Republic Survived in the Shadow of the Third Reich

(Staplehurst: Spellmount, 2006).

10

. ‘Schwerin, Gustloff’s Funeral: Speech of February 12, 1936’. www.hitler.org/speeches/02-12-36.html.

11

. Peter Bollier, quoted in Halbrook,

Swiss and the Nazis.

12

. Kimche.

13

. Jean-Jacques Langendorf and Pierre Streit,

Le Général Guisan et l’esprit de résistance

(Bière: Cabédita, 2010).

14

. Kimche.

15

.

New York Times

, 25 July 1999.

16

. Halbrook,

Target Switzerland.

17

. Halbrook,

Target Switzerland.

18

. Halbrook,

Target Switzerland.

19

. Kimche.

20

. Kimche.

21

. Shirer,

Rise and Fall.

22

. Shirer,

Rise and Fall.

23

. Shirer,

Rise and Fall.

24

. Joachim C. Fest,

Hitler

, tr. Richard and Clara Winston (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1974).

25

. Shirer,

Berlin Diary.

26

. Cicely Williams,

Zermatt Saga.

All during the last months they [the Nazis] had in the most shameful manner persecuted, killed and imprisoned thousands of Jews from all over the country.

MARIA VON TRAPP

By mid-October 1940 it had become clear to Shirer in Berlin that the invasions of both Great Britain and Switzerland had indeed been postponed for the remainder of the year. When the spring snows melted, General Guisan might have to remobilise his army. In the meantime, most of his troops could revert to their normal occupations as – in Hitler’s eyes – herdsmen and cheese-makers with some armaments manufacture and spying thrown in. It was a stay of execution, and Shirer won his bets with the Wehrmacht top brass who had been so confident of flying the swastika in Trafalgar Square before the clocks went back. ‘I shall – or should – receive from them enough champagne to keep me all winter.’

1

The reprieve, though, had consequences. On 15 October 1940 Shirer noted, ‘This winter the Germans, to show their power to discipline the sturdy, democratic Swiss, are refusing to send Switzerland even the small amount of coal necessary for the Swiss people to heat their homes. The Germans are also allowing very little food into Switzerland, for the same shabby reason. Life in Switzerland this winter will be hard.’

2

It was the same throughout the Alps. Six years hence Churchill would remark in his epochal speech in Fulton, Ohio, ‘From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the continent.’ For the present just such

a totalitarian pall had fallen on the Alps from Mont Blanc to the Grossglockner, the highest peaks in France to the west and in Austria to the east. Only the Alps in Switzerland remained politically free – but they were scarcely unfettered. On 24 October 1940, Shirer was himself in Switzerland on a visit to Berne. ‘A sad, gloomy trip up from Geneva this afternoon. I gazed heavy-hearted through the window of the train at the Swiss Lake Geneva, the mountains, Mont Blanc, the green hills and the marble palace of the League that perished.’

3

Darkness had fallen on the Alps, the ‘visible throne of God’.

*

The shadow had fallen over Switzerland’s neighbouring Alpine republic of Austria two and a half years previously. In the Alpine city of Salzburg overlooked by Hitler’s Berghof, a member of the Austrian gentry recalled:

It was March 11, 1938. After supper we went over to the library to celebrate Agathe’s birthday. Someone turned on the radio, and we heard the voice of Chancellor Schuschnigg say:

‘I am yielding to force. My Austria – God bless you!’ followed by the national anthem.

We didn’t understand, and looked at each other blankly.

The door opened and in came Hans, our butler. He went straight to my husband and, strangely pale, said:

‘Herr Korvettenkapitän, Austria is invaded by Germany, and I want to inform you that I am a member of the [Nazi] Party. I have been for quite some time.’

Austria invaded. But that was impossible … At this moment the silence on the radio was broken by a hard, Prussian-sounding voice, saying: ‘Austria is dead: Long live the Third Reich!’.

4

So the breaking news of Anschluss was remembered by Maria von Trapp in the city of Mozart.

As the film

The Sound of Music

portrays with, for Hollywood, surprising fidelity to fact, the von Trapp family was aghast at this turn of events. At first the singers were in a tiny minority. One reason for the invasion was a referendum on Austria’s

independence

planned by Chancellor Schuschnigg for 13 March 1938. Fearing a pro-Austrian result, Hitler sent in his troops. But when

on 15 March the Führer spoke from the balcony of the Hofburg Palace, the seat of the old Habsburg monarchy in Vienna, he was fêted by around a seventh of the country’s population – perhaps a quarter of a million people; when the plebiscite on Anschluss was held three weeks later on 10 April, 4,453,000 of an electorate of 4,481,000 turned out. Of those, 99.73 per cent supported the dissolution of their nineteen-year-old republic.

There were various mitigating circumstances. Not least amongst these was the absence of any opposition party, or indeed support for Austria’s independence from neighbouring Italy or the mother of democracies, Great Britain. It is also more than doubtful as to whether the vote was ‘free and fair’ – as the Austrian resistance leader Fritz Molden later pointed out in his memoirs.

5

Still, 99.73 per cent is 99.73 per cent.

The Nazis – both German and Austrian – then began to put the lamentable affairs of the new Alpine province of the German Reich into order. First came the arrest and imprisonment of those deemed by the new chancellor Arthur Seyss-Inquart as unsympathetic to the Nazi cause. Around 20,000 were seized on the night after Anschluss. Some of these enemies of the Reich would eventually find their way to Dachau in Bavaria. As this was 300 miles away from Vienna, that very month Heinrich Himmler – in his capacity as Reichsführer-SS – had the idea of establishing something comparable on Austrian soil. Since 1934 the SS had managed the concentration camp system under a formation known – after their skull-and-crossbones insignia – as the ‘death’s head unit’: SS-Totenkopfverbände. A granite quarry at the confluence of the Danube and Enns was identified as a possible site. The quarry could usefully provide the raw materials for the rebuilding of the Reich along the grandiose lines envisaged by Hitler and his tame architect Albert Speer. The city fathers in Vienna duly endorsed the idea of a camp to accommodate up to 5,000 prisoners. The one proviso was that it would provide cobblestones for the streets of the city of Mahler, Strauss, Wittgenstein and Freud. Work proceeded apace and the site received its first 300 inmates on 8 August 1938. The camp

was Mauthausen, which would spawn a series of subcamps all over the Alps of Austria and Bavaria.

Many of their inmates were of course Jews. The Nuremberg Laws of 1935 had deprived Semites of their citizenship, banned marriage between Jews and other Germans, and forbidden them to practise various professions, so preventing many of them from earning a living. With Anschluss, these laws applied in Austria. Here there was a Jewish population of around 192,000. Shirer recalled their treatment in Vienna in the immediate aftermath of Anschluss:

There was an orgy of sadism. Day after day large numbers of Jewish men and women could be seen scrubbing Schuschnigg signs off the sidewalk and cleaning the gutters. While they worked on their hands and knees with jeering storm troopers standing over them, crowds gathered to taunt them. Hundreds of Jews, men and women, were picked off the streets and put to work cleaning public latrines and the toilets of the barracks where the S.A. and the S.S. were quartered. Tens of thousands more were jailed. Their worldly possessions were confiscated or stolen.

6

At this stage in its gestation, Nazi policy on the Jewish question was to encourage emigration. The focus of this programme was the Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung (Central Office for Jewish Emigration). This was set up on 22 August 1938 by the notorious architect of the Holocaust, the thirty-two-year-old Adolf Eichmann, suitably located in the former Rothschild Palace in Vienna, home of the Jewish banking dynasty. In Salzburg, 250 miles west of the capital, the matriarch Maria von Trapp remarked of that summer, ‘All during the last months they [the Nazis] had in the most shameful manner persecuted, killed and imprisoned thousands of Jews from all over the country.’

7

*

Still, some Austrians undoubtedly supposed that the Nazis’ crushing of civil liberties in 1938 was compensated by material advancement. Fascism was a child of the Depression that for Austria was epitomised by the collapse of the Creditanstalt Bank in May 1931. The von Trapps themselves were victims of another

bank collapse in 1935, the spur to their careers as professional singers. Inflation and unemployment – Arbeitslosigkeit – were the two great evils of the day. In Austria, unemployment at its height stood at one million out of a population of only six million. At the time of Anschluss, about 10 per cent of the workforce or 400,000 were unemployed. Two years later the figure had fallen to 250,000. Amongst the beneficiaries of the economic upturn were the resorts in which Alpine Austria – Carinthia, Upper Austria, Salzburgerland, Tyrol, Vorarlberg – abounded. Here, visitors from within Austria began to return; so too did those from Germany. Hitherto the Nazis had done their best to strangle tourism in Austria by requiring German citizens – the country’s principal visitors – to buy a 1,000-mark visa. This was dropped, and an exchange rate was agreed between Seyss-Inquart and Hitler that made the major resorts attractive destinations. In the winter and summer seasons that immediately followed Anschluss – winter 1938–9, summer 1939, winter 1939–40 – the resorts flourished.

Frau Inge Rainer was born in the Tyrolese resort of Kitzbühel in 1929, and brought up in the pension run by her family. Her memories are vivid of the poverty of the valley in the thirties. ‘Not everyone had a pair of shoes, and I remember one day my father cutting up a small piece of boiled beef on his plate into five pieces. One for himself, one for my mother, and the three remaining for myself and my siblings.’ Anschluss for her was like day after night. ‘When Anschluss came everything changed for the better. Immediately everyone had a job and I joined – you had to join – the Hitler Youth. This was a lovely thing to do. There were competitions in sport, singing, dancing. We had a uniform, went camping, did things that had never happened before.’ For Frau Rainer, the popular enthusiasm for Hitler was entirely understandable. He brought full employment. ‘That’s why everyone voted for him.’

8

The resistance leader Fritz Molden commented, ‘a great many Austrians regarded Hitler as a liberator, if not actually a Messiah’.

9

*

For some, though, Austria in her new manifestation remained untenable. Georg Ludwig von Trapp – the Captain in

The Sound of Music

– had been a distinguished submariner in the old Austro-Hungarian Navy. In the course of the First World War, he completed nineteen war patrols and sank 45,669 tons of shipping. Much of it was British.

In 1936 he was approached by the Kriegsmarine to command a new U-boat, and eventually to establish a submarine base on the Adriatic. This he had the courage to turn down. Then in August 1938, the family was told they had been chosen as representatives from the new Ostmark to sing to the Führer on the occasion of his fiftieth birthday in April 1939. In a sense this was wonderful news. As Maria von Trapp candidly recorded: ‘This meant we were made. From then on we could sing morning, noon and night and make a fortune!’

10

The family spurned the honour. Contrary to Hollywood’s account, they did not set off at night over the Alps to Switzerland – which were inconveniently 180 miles away. To avoid arousing suspicion, they did in fact leave the house in Salzburg in their traditional Austrian garb of lederhosen and dirndls, saying they were going climbing in the Tyrol. In fact they took the train to Italy, then to England. In October 1938 the von Trapps set sail on the SS

American Farmer

from London for New York, fame and fortune.

They were the lucky ones. When war broke out in September 1939, the Austrians’ unbridled enthusiasm for Hitler had somewhat cooled. A mass anti-Nazi protest of 10,000 in Stephansplatz in Vienna on 7 October 1939 was the beginning and end of such demonstrations. The rally was broken up and the leaders ended up in Mauthausen and Dachau. A year later, as the reality of war began to settle on the Austrian people, a carpenter’s apprentice in Herzogenburg was brave enough to tell the Gestapo, ‘The English have never lost a war, and they are going to win this one as well.’

11

Back in Berlin, Shirer was beginning to be of the same opinion, for there was wonderful news from the United States. On 6 November 1940 Franklin D. Roosevelt was re-elected as President for a third term.

It is a resounding slap for Hitler and Ribbentrop and the whole Nazi regime … because Roosevelt is one of the few real leaders produced by the democracies since the war … I’m told that since the abandonment for this fall of the invasion of Britain, Hitler has more and more envisaged Roosevelt as the strongest enemy in his path to world power, or even to victory in Europe.

12

For Shirer, the news was particularly welcome because of a story that had been brought to his ears the previous month and which he was now investigating. It had horrified a man inured to the evil of the country he was covering, and it was entirely emblematic of the Nazis’ rape of the Alps.

Irmgard Paul was born in 1934 and brought up in

Berchtesgaden

. In 1930 her father had taken a job in the Bavarian resort in a workshop for hand-painted porcelain. Her mother had followed him there, and the couple married in 1932. At the time, the place where they settled – Obersalzberg – knew Hitler and his Berghof but had yet to become subsumed into the Nazi HQ. In 1933 Hitler became chancellor and the Nazis’ grip on the country tightened very quickly. Irmgard remembered that

when I was born into our mountain paradise the Nazis were in full control of all branches of government, the military, and the media. And they had begun to infiltrate all aspects of life and to dictate the everyday details of family decisions: our education, the books and the news we read, how we greeted one another – even the names parents gave their children.

13

As a three-year-old in the summer of 1937 Irmgard was taught by her father the straight-armed Nazi salute and the greeting ‘Heil Hitler’. This was fortuitous. That autumn the family took the opportunity of a blissfully warm day to walk up to Obersalzberg to see the newly enlarged Berghof. When they reached the fence

that divided the Führer from his people, they joined a crowd of pilgrims hoping for a glimpse of their leader.