Storms of My Grandchildren (27 page)

Read Storms of My Grandchildren Online

Authors: James Hansen

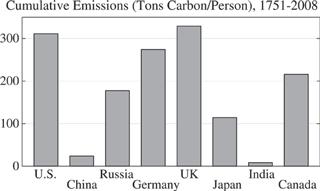

I had one additional argument for giving a speech in the U.K.: On a per capita basis, the U.K. is more responsible for the climate problem than any other nation. That may be surprising, given that the U.K. produces less than 2 percent of global fossil fuel emissions today—the United States and China each burn more than ten times as much fossil fuels. But climate change is caused by cumulative historical emissions. The fraction of carbon dioxide emissions remaining in the air today is much less for older emissions than for recent emissions, due to carbon uptake by the ocean and biosphere. But the greater diminishment of older emissions is compensated by the fact that they have had more time to affect climate. The result is that the U.K., United States, and Germany, in that order, are the three countries most responsible, per capita, for cumulative emissions and climate change, as shown quantitatively in

figure 24

.

FIGURE 24.

Cumulative per capita carbon dioxide emissions, with countries listed in the order of national cumulative emissions. (Data sources are Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, and British Petroleum.)

I gave talks in London in March and July of 2007. Both trips included dinners with people who, it was hoped, might be able to influence policies. At one of the dinners, on U.S. Independence Day (July 4), my argument that new coal-fired power plants must be stopped as a first step toward phasing out coal emissions evoked discussion in favor of a specific action. The group would write a letter to try to influence plans to expand an existing coal-fired power plant. I contributed science rationale for the letter.

Later in the year, as it was clear that plans for expansion of coal-fired power were continuing apace in the U.K., Germany, and the United States, and even more so in China and India, I decided to write a letter to the U.K. prime minister, by then Gordon Brown. If Prime Minister Brown wanted to exert leadership in the climate problem, I wrote, a moratorium on new coal-fired power would be the way to do it, and would be more effective than a “goal” for emissions reduction. Such an action would put the U.K. in position to argue that Germany and the United States, both planning to build more coal plants, should also have a moratorium. Until Europe and the United States stop building new coal plants, there is little chance of fruitful discussions with China or India—and no hope of solving the climate problem.

The letter was taken by U.K. contacts to appropriate people in the prime minister’s office. My hope was to get the U.K. government to think about the problem in a different way, to recognize that goals for emission reduction, however ambitious, will not work. There is a limit on how much carbon dioxide we can put into the air, and the only realistic chance of staying under that limit is to cut off coal emissions to the atmosphere soon. I believe my letter to the prime minister, which I made public on my Web site, was the clearest explanation that I had made of this concept. Unfortunately, the official response, via a letter to me from the Department of Environment, was tantamount to a restatement of the U.K.’s prior positions and plans.

I had already decided to write a letter to German chancellor Angela Merkel, before receiving a response from the U.K. government. Merkel was trained as a physicist, and I hoped that, rather than relying on advisers, she would be willing to think about the problem herself. I figured she would be able to appreciate the geophysical boundary conditions, the conclusion that most of the coal must be left in the ground.

My letter to Chancellor Merkel was similar to my letter to Prime Minister Brown. I sent a draft of the letter to German scientists and environmentalists, who provided helpful suggestions on details and protocol to optimize the chances that my suggestion would be considered seriously. A German environmental organization, GermanWatch, arranged translation of the letter into German for publication in a major German newspaper,

Die Zeit

.

An open letter, it seemed to me, was probably the best way to affect the coal discussion in Germany. However, John Schellnhuber, climate science adviser to the German government, suggested that it would be better if I held off on publishing the German translation and instead traveled to Germany for discussions. Specifically, Schellnhuber argued that the only way to get Germany to change its position was to persuade Sigmar Gabriel, minister for the environment, of the need to do that. Gabriel was in charge of German efforts to control the country’s greenhouse gas emissions, and Merkel relied on him for policy advice.

My trip to Germany began with a useful visit to the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, of which Schellnhuber is director. I gave a seminar at the institute to initiate a discussion, the objective being to make sure that we were in basic agreement on the science issues to be addressed with Minister Gabriel. The scientists at the Potsdam Institute include Stefan Rahmstorf, one of the world’s leading researchers on climate change. Rahmstorf has a broad understanding of the science and an ability to explain things to the nonscientist, so it was useful that he agreed to attend the meeting with Gabriel.

That meeting lasted about ninety minutes. In the first part of the discussion I provided reasons for a carbon dioxide target of no more than 350 ppm—explaining the need to avoid ice sheet disintegration, species extinction, loss of mountain glaciers and freshwater supplies, expansion of the subtropics, increasingly extreme forest fires and floods, and destruction of the great biodiversity of coral reefs. This part of the meeting went very well. There was no disagreement about the need to aim for a limit of 350 ppm on carbon dioxide.

The sticking point was the implication: the need to halt coal emissions. Germany had plans to build several more coal-fired power plants. Our discussion circled back to this issue repeatedly, as I argued that the climate problem could not be solved if coal use continued. I asked how, if Germany was going to continue to burn coal, it would persuade countries such as Russia to leave its oil in the ground. Gabriel’s answer: “We will tighten the carbon cap.” I pointed out that a cap slows emissions but does not prevent usage of the large pools of oil and gas reserves. A cap, or a carbon tax, is useful—indeed, necessary—to spur technologies needed to supplant fossil fuels, so that marginal reserves (fossil fuels that are difficult to extract) can be left in the ground. However, a cap does not prevent readily accessible oil and gas from being extracted. We went around this circle several times.

Then, in the final minutes of our meeting, the underlying story emerged with clarity: Coal use was essential, Minister Gabriel said, because Germany was going to phase out nuclear power. Period. It was a political decision, and it was not negotiable.

As we stood up to leave, Gabriel asked me whether I had an appointment to see Merkel. He seemed satisfied that I did not. On the trip back to the United States I had the feeling that perhaps I had missed an opportunity. I should have been more involved in defining the arrangements for the trip—conceivably I could have obtained a meeting with Merkel, especially if I had made such a meeting a condition for withdrawing the letter from the media. That leverage had been lost by the time of my meeting with Gabriel, as the letter was old news by then.

Two weeks later I went to Japan, where I had been asked to give a keynote talk at a symposium at the United Nations University, whose main campus is in Tokyo. The symposium’s purpose, as described in the letter requesting my talk, was “to raise public awareness in Japan and internationally about the challenges and emerging approaches to climate change in advance of the forthcoming G8 Summit to be held in Hokkaido, Japan. The specific objective is to bring together some of the world’s leading scientists and writers on environmental issues, groundbreaking thinkers at the intersection of science and communications, to examine how our thinking needs to change if we are to collectively take on the myriad challenges presented by global warming.”

That was an opportunity—or an obligation—that I should not turn down. Japan was the perfect place to clarify the implications of science for policy. It was the birthplace of the Kyoto Protocol, the first attempt at international climate policy, which expires in 2012. Before a follow-up international agreement is defined, the scientific method and common sense suggest that we look at evidence from that first attempt.

So I would focus my lecture at the UN University on lessons from Kyoto. I also would write a letter to Japanese prime minister Yasuo Fukuda. Japan—which had been exemplary in living up to the treaty obligations—was not the target. I could have written my letter to the G8 leaders, but there was a better chance of gaining attention in Japan with a letter to the prime minister. Ultimately it is the public that must become informed and place pressure on our governments, which do not appreciate the lesson that Kyoto has delivered.

Before discussing the letter to Fukuda, we should consider lessons from Kyoto. The Kyoto accord, I could show, is fundamentally flawed. Yet a repeat of the Kyoto approach, with tightened caps, is exactly what the international community has been focusing on for the next international agreement. Altogether the Kyoto experience points to what not to do, but it also can help us define a more basic, workable approach.

The Kyoto accord was doomed before it started, because it did not attack the basic problem. The Kyoto Protocol set emissions reduction targets for developed countries, with targets negotiated individually with each country. Developing countries were not required to reduce emissions, but the Kyoto accord attempted to reduce the growth of their emissions through the Clean Development Mechanism, which allowed industrialized countries to make investments aimed at reducing the growth rate of developing countries’ emissions in lieu of their own.

One flaw in the Kyoto approach is that targets for emissions reduction do not work, regardless of whether they are voluntary or “legally binding.” Most countries demand concessions or a favorable target before they will agree to a target, or before they will ratify an accord. Russia, for example, agreed to the Kyoto accord only after it became clear they could achieve their target without serious effort, and thus they would be able to sell emission allowances to countries that failed to meet their own target. Another problem with targets is that there is no good way to prevent a country from overshooting its target, as many countries did.

Offsets are another of Kyoto’s flaws. If a country finds that it is too inconvenient to meet its carbon emission reduction target, it can purchase the right to exceed its emissions target. In other words, it “offsets” its excess emissions via an action that supposedly reduces greenhouse gas emissions someplace on the planet.

Supposedly.

But only rarely do offsets actually cancel the climate effect of an overshoot in emissions, and the offset approach can even have a reverse effect. The offsets often occur, or supposedly occur, in developing countries, which will sell offsets at a low price. The existence of offsets discourages developing countries from improving their energy efficiency or reducing their greenhouse gas emissions, because the more emissions they have, the more actions they will have to sell as offsets to developed countries under the Clean Development Mechanism. Entrepreneurs in China even produced chlorofluorocarbons solely so they could be sold to developed countries and destroyed, thus providing bogus or imaginary offsets. Other offsets are practically unverifiable or temporary, for example, tree plantings in developing countries. But even if the tree planting is legitimate, I showed in chapter 8 that reforestation is not an alternative to fossil fuel phaseout—

both

actions are required to get the carbon dioxide amount back below 350 ppm.

Now let’s look at the empirical evidence for how well the Kyoto Protocol worked. And let’s look at Japan specifically, as well as the global result. Japan’s success should be a poster child for the rest of the world. It is well known that Japan works very hard at energy efficiency; it may be the most energy-efficient nation in the world, at least in industrial processes. Japan has good reason to minimize its fossil fuel use, because it has little indigenous fossil fuel supply.

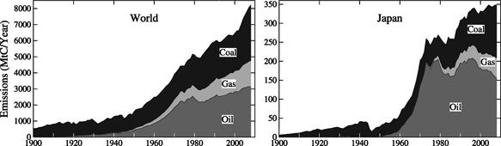

Figure 25

shows fossil fuel carbon dioxide emissions, by fossil fuel type, for the world and Japan. Japan did not meet its Kyoto emissions reduction target, even with the help of offsets—instead, its fossil fuel emissions increased. Global emissions skyrocketed. There was a substantial reversion to coal—the oldest, dirtiest fossil fuel.