Straight Life (38 page)

I noticed that both these guys had the same animated look about them, and their eyes were sort of red. Right away I thought, "Juice!" They each had a can. They whisper, "Art Pepper?" And I say, "That's me." The first guy says, "I'm Don Proffit, man." He says, "I've been a fan of yours for years. I'm an actor. I heard you were coming. This is my friend, Huero." Huero says, "I've known a lot of cats that have known you. They say you're good people. We figured since you just drove up it must be a little scary, so we brought you something to take the edge off." Huero puts his can through the bars and Don puts the other one through. It's pisco, a drink they make out of all kinds of things, fruit and yeast. It's home brew. It looked like a dull orange juice, kind of pissy looking, and it tasted like rotten beer. I looked at the other cat in the cell. They asked him, "Who are you?" Huero said, "I hope you realize that in a place like this if someone does you a favor you never say anything about it or get them in trouble. You're with our friend and we don't want to leave you out, so remember, if anything happens, you get too drunk or you get busted, you ride the beef." The guy was so sad. I said, "He'll be alright."

We started drinking this stuff and talking. Don told me about his acting. Huero loved my music. All four of us got really loaded; we had a ball. We finished the two cans, so Huero climbed back over the walkway, and a few minutes later I saw his arm coming up again and this can, and here he comes after it. They went through this whole scene and never got busted. It was like the thing that happened in Soledad. I was afraid San Quentin would be different, that there was some other breed of people here. But I saw that it's just people, and there's groovy people everywhere. I drank so much I got sick. They left and they said, "We'll see you tomorrow." I vomited, and I got up in my bunk, and I thought, "Well, maybe it's not so bad after all." And I got that warm feeling of having friends, male friends, good people; I was liked and it made me feel good. I passed out.

All of a sudden I heard this clanging of gates. It was a horrible sound, and I woke up and looked down and saw this toilet with vomit all over it. My cell mate was still asleep. I couldn't understand how he could still be sleeping with all the noise that was going on. I threw some ice water on my face, and they racked the gates and called us out, and we went to the mess hall.

The coffee tasted good. After we ate they took us to the clothing room and we got our blues, a blue shirt and pants made out of a kind of denim, and brown shoes-"Santa Rosas"-old man type shoes with the line across the toe. I was very happy to be out of the jumpsuit; I felt less conspicuous. But I found out later it wasn't the clothes that made me conspicuous. I learned that even with six thousand people I couldn't just blend in with the crowd. Everyone knew we had just drove up. One of the guards told us some of the details. He told us what we should and should not do. He told us you get one to life for attempted escape. He pointed out the walkways and told us the guards were all expert shots. He said just do right and everything'll be okay.

It so happened we got there on Friday, so my first day was a Saturday and we were more or less free until Monday. When I arrived I'd seen several people I'd known before, and when I walked out of the clothing room here was a real good friend, Little Ernie Flores. He was one of those prematurely grey people, his hair had turned almost completely. His bone structure was Indian, but he was very small and dapper. He saw me and he said, "Heeeey, Art!" I looked at my clothes. They were old, wrinkled blue denim. He was wearing the same thing but it was that slightly different color, and he was all pressed, real sharp. Instead of the Santa Rosas he had loafers; they were shined. He looked great. The last time I'd seen him on the streets he'd had a lung operation and he was really messed up. Now he was healthy and clean, and it made me feel good to see him like that. He said, "Come on, I'll show you around." He noticed me looking at his clothes and at my own and he said, "Oh, don't worry about that, man. I'll fix you up. Come on."

Little Ernie was working in the employees' dry cleaning plant. He was the lead man there. We had some small talk and walked around, and he said, "It's not as bad as it seems. I know how you feel because I felt the same when I first drove up, drug and panicked, but you've got friends here, and everything'll be alright."

We walked around the big yard, and he showed me the canteen line. You can buy a book with duckets in it, coupons for however much money you draw, which you use to pay for things from the canteen. You get a new book each month, and no one can steal it from you because only you can cash your own duckets. You can buy these books if someone sends you money, or you can have someone that's in the jail put money on your books, or you can get a job and get paid. Eventually I got a job paying six dollars a month, but the prison deducted a dollar and eighty cents from that for the "inmate welfare fund," which they said was for movies and canteen, leaving me with four dollars and twenty cents a month, still a lot of money.

Little Ernie showed me the big yard. The cell blocks formed the walls of the yard and right in the middle was a tower with a shed on it and a walkway so the guards could walk out to it with rifles. I looked around this big area and everywhere I looked I saw groups of people and I could see that they were, like, cliques. A group of Mexicans, a group of blacks, a group. of whites. Each group talking, and all kinds of action going on. In the middle of the yard, to the left of the shed, was a bunch of picnic tables. I saw guys standing around them real intent. I walked over with Ernie and he said, "This is the domino tables." They played dominoes because cards weren't allowed. They made their own dominoes out of plastic and wood and glass, and they were beautiful. They played for cigarettes-that was money in prison. And I learned that many people were killed because of debts incurred at the domino tables. In San Quentin you could work or not work. If you chose not to work, you'd just wander around the yard. Those were the guys that played dominoes. Those were the guys that if any dope came in they had some action. They were living just like on the streets, hustling and scuffling.

Ernie said, "Let me show you the lower yard." The lower yard has a football field, a baseball diamond, and handball and basketball courts. We started down the stairs and as we went down I saw a guy coming up, and he looked really strange; he looked like a ghost. He had his hands on his stomach, and I saw that there was blood running out all over his hands. As we got close to him he let go of his stomach to grab the rail because he was starting to fall, and he was just covered with blood. I said to Ernie, "Oh, man!" And I started to go to the guy's aid, but Ernie grabbed me and said, "Come on, come on, come on! Hurry!" He was frantic. We got down the stairs, and as we reached the bottom I looked back, and here was the guard on the walkway above the stairs with his rifle pointed at the guy. Ernie said, "Now, if we had stayed there to try to help him we would have been right in the middle of this shit. There's no telling what might have happened. I know it's cold. We haven't been brought up that way. But you have to mind your own business and keep walkin'." I said, "What happened?" He said, "Oh, those things happen here all the time. Somebody shanked the guy. They get a piece of metal from the machine shop and sharpen it into a dagger, and they put tape over the handle part."

The only photograph of my mother, my father, and me together.

My father who, more than any other person, molded my personality and way of thinking. Photo courtesy of Thelma Pepper.

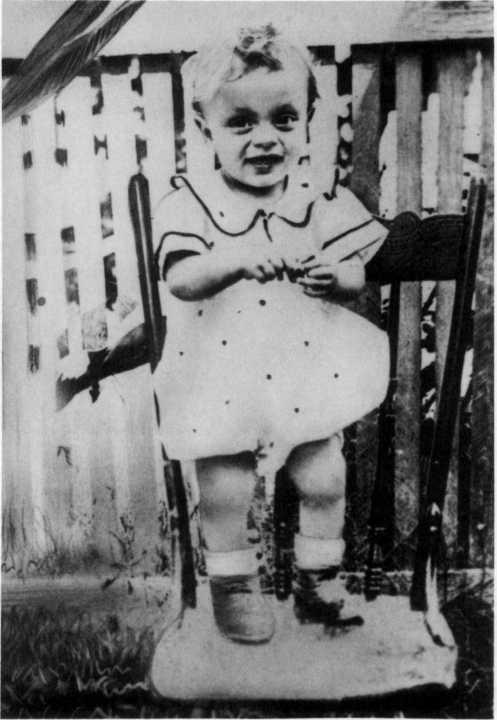

Me at about age one. "There was another time when they were separated for nine months and junior lived with Grandpa Joe and Grandma in Watts. Grandma took care of him then, and that's when he made the most progress physically." Photo courtesy of Thelma Pepper.

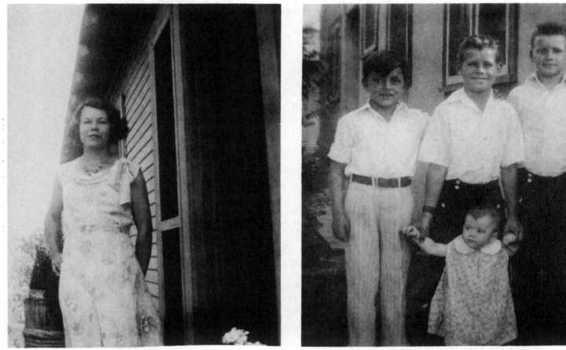

(Left) Thelma, later my stepmother, in 1932; one of the nicest, most sincere and honest persons I've ever known. Photo courtesy of Thelma Pepper. (Right) Me (on the left) with Thelma's children-Bud, John, and the little one, Edna. Photo courtesy of Thelma Pepper.

My mother and I in downtown Los Angeles. I was about 13.

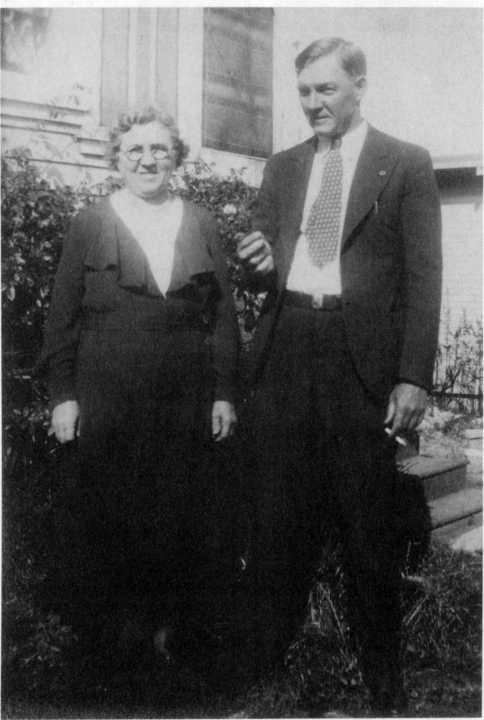

My grandmother and my father. Photo courtesy of Thelma Pepper.