Strange Light Afar (8 page)

Read Strange Light Afar Online

Authors: Rui Umezawa

“I really must go home today.”

“Nonsense.” She brushes her lips across my temple. “We are just getting acquainted.”

She wants to know more about me. I start by explaining how my father drowned at sea years ago.

Somehow I spend the entire morning telling Oto of how my mother nags me to go out with the boats, how she refuses to buy me sake when I ask and how she always compares me with my father. He caught more fish than anyone in the village. We never had to worry about anything when my father was around.

Oto nods knowingly and pulls a strand of hair from my eyes. Her sleeve smells like peach blossoms.

That afternoon, moving bronze statues of imperial guards treat us to demonstrations of amazing physical feats. I watch them swing their swords and jab their spears. I sip distilled spirits made from millet and nibble on grilled squid. Oto fills my cup each time it is empty. She gasps when a guard smashes a brick into pieces with his forehead.

My head is starting to ache also. Spinning plates and acrobats parade by my field of vision. Lunch seamlessly turns to dinner.

Then Oto and I kiss. That is the last thing I remember.

Fits of sleep flow into one another. Waking hours become indistinguishable from dreams. More food. More dancing. More drink. Oto's soft laughter, her flawless skin, her warm breath. Light and dark circle each other in a timeless dance. Idleness succeeds in doing what the sea could not. It drowns me.

I cannot recall when I first notice that shadow has overwhelmed color. The familiar darkness is suddenly there one day. Maybe it was never gone. The smooth marble floor that once seemed perfectly flat tips sickly to one side. Cold returns to the hollow space that is my chest.

Seeing my mother's weathered skin on Oto's smooth face is like a sick joke I play on myself. The smell of fish brings to mind my discarded nets. Among the song and dance, I yearn for the quiet of the empty seaside. All I can think of to ease the pain in my head and the churning in my belly is to drink more, but relief fades as soon as it appears. I vomit more times than I can count.

“Leave me be!”

I flail my arms as Oto's hands flutter about me. She implores me to bathe, then to sleep. I seek oblivion while terrified of it. Fear hands me the sake cup, which I throw at her. It narrowly misses her head and shatters when it strikes the pillar behind her.

She leaves with a remarkable calmness and does not return for a long time. I cannot eat or sleep so instead thrash about in a pool of anger and self-pity.

When Oto returns to the chamber, there are two imperial guards with her.

“I think it would be best if you leave,” she says firmly. “My father allowed me your company only to please me, which you are no longer able to do.”

I sneer. “But you will be all alone again.”

“And I shall be the better for it. I for one do not mind being secluded among the pleasures of this palace. Besides, someone else will come along soon enough. You do understand that, don't you?”

She turns her gaze to the floor, then waves over a guard who is holding a silver tray. On it sits a lacquer box tied with braided gold rope.

The hardness in her voice is suddenly gone.

“Do not think ill of me. I truly am very fond of you. Please permit me the honor of presenting you with this gift.”

I fidget nervously, not knowing where to put my hands. She ignores this and gives me the box.

“Should you decide you can enjoy what this palace has to offer in a civilized manner, bring this back to me unopened. I shall be more than pleased to see you return. If you choose to stay away, however, I shall understand. Open this gift then to remember me by.”

I want to smash the box on the floor. But I notice one of the guards firmly grasp his sword and know to still myself.

She turns and walks away. I hear faint music floating from down the hallway.

The turtle does not offer me any words of comfort on the return journey. I know better than to expect it. The shore is barren when we break the surface of the water. The turtle drops me off on the warm sand before disappearing back into the depths. The sea breeze is as gentle as the sky is blue. So blue.

A few children scatter about the huts as I walk back into the village, but they are not the same boys who had been tormenting the turtle a few days earlier. A woman draping wet laundry over a bamboo pole nods at me politely but cautiously. I do not recognize her. She must be visiting one of my neighbors.

I loudly announce my return before crossing my threshold. Our hut is barren, and a few moments pass before I notice that everything is covered in dust. Streams of cobweb hang from the corner of the ceiling, swaying in the draft.

I call out to my motherÂ

â

once, then three times more. Her absence is at once annoying and unnerving.

I leave the hut and walk back to the woman who has just hung her last piece of laundry. She wrinkles her nose. The wind has picked up.

“Sorry to disturb you, but have you seen the woman who lives in that hut over there?”

“No one lives there.”

“What?”

“No one has lived there since Mrs. UrashimaÂ

â

”

“That's my mother. Where did she go?”

The woman arches her brow. “You must be mistaking her for someone else. Mrs. Urashima had no family. Her husband was killed in a storm and her only son

â

”

“That's me! I'm her son! Where is my mother?”

The woman seems genuinely confused now. She takes a few cautious steps backwards.

“She's dead,” she offers carefully.

The words fall to the ground like anvils. I feel my knees give but somehow manage to remain standing. Dizziness returns, muddled with anger and confusion. This must show in my face. The woman retreats a few more steps.

“I tell you there's some mistake,” she assures me. “Mrs. Urashima's boy ran away forty years ago. His name was Taro.”

Clearly she is right. There is some mistake, and she, being a stranger to our village, is misinformed. I leave her holding her empty basket and run to other huts. StrangersÂ

â

women and children, because the men are still out on their boatsÂ

â

look at me. They do not recognize me, and I do not recognize any of them. There is no one I can ask about my mother.

I go back to our hut and ponder what to do next. The most likely explanation is that my mother has gone looking for me. I ignore the fact that the village is now full of strangers. One mystery at a time.

I spend the next while rummaging through the kitchen. There is nothing to be found. Most disappointing is that there is no sake.

Then I remember Oto's parting gift. The lacquer box is still spotless, its sheen unworn from the journey home.

When I untie the knot and remove the lid, a bright light is followed by a dense wall of smoke. There is no sound, and I am able to breathe comfortably, though I cannot see anything.

Something shifts beneath the skin on my face. My legs turn weak and I need to sit.

I look at the polished lid in my hand. As the smoke clears, I gradually make out my reflection and see that my hair has turned white. Folds of skin hang over my eyes. I notice that my hands are gnarled and stiff, a constellation of liver spots on their backs. When I cry out in horror, a few teeth spill from my mouth.

The woman who was hanging her laundry hears my cries and comes running. Perplexed, she stands over me. There is not even a trace of recognition in her eyes. She calls me “old man” and asks where I am from.

Here, I want to tell her. I want to tell her I am from here, but the words cannot struggle free.

She reaches down and strokes my hand sympathetically as I sob uncontrollably. There, there. She tells me everything will be fine. Just fine. She is gentle and kind despite her confusion. I squeeze her hand before pulling it toward my face. She leans in closer. I lose myself in her reassuring whispers. I cannot resist the comfort they offer.

Who could blame me for that, given all that I've been through?

EIGHT

BETRAYAL

â

H

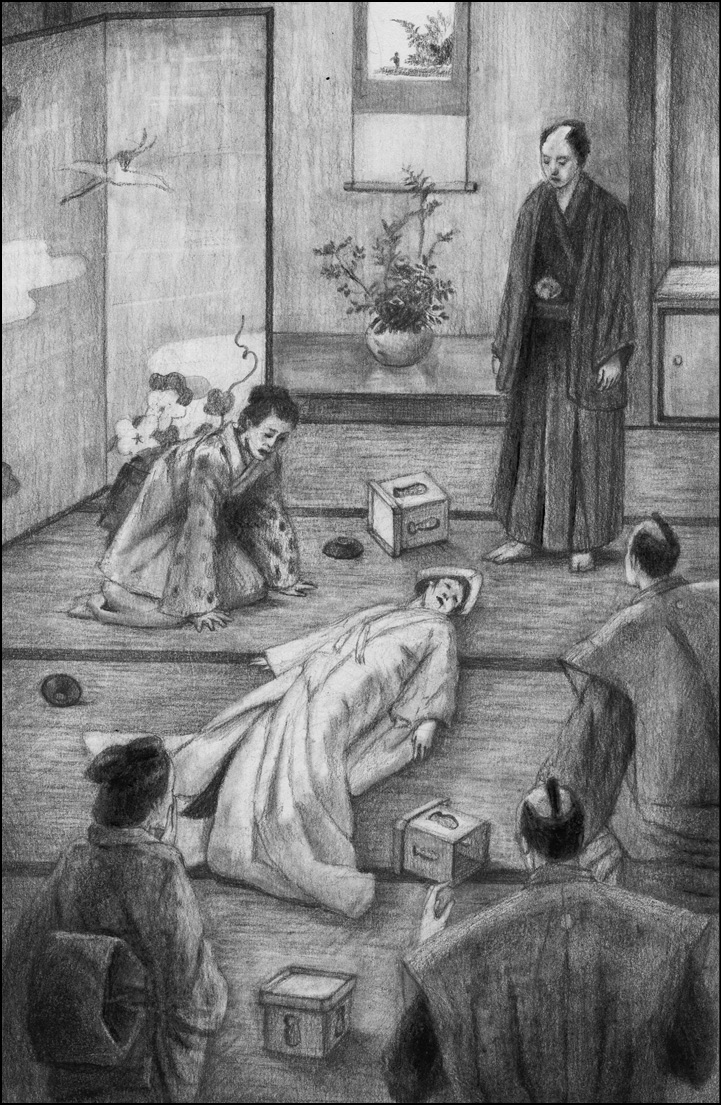

ere is Oiwa, combing her fingers through her long shimmering hair. To her horror, strands like silk fall with each stroke. She cries out, but nothing much passes through her throat. She chokes, instead.

She tries to stand, but her knees fail. Clawing at the door, she tears into the rice paper, and a panel crashes down as she falls. She manages to spill into the hallway on her hands and knees. Blood cascades from her lips as she crawls toward the kitchen.

She can hardly see the lamp her husband is holding over her.

“Water!” she hisses. “Please!”

Tamiya fidgets. This is turning out much uglier than he'd intended.

“Water!”

Her eyelids swell hideously. Tamiya hates ugly things.

â¢

They met on the brightest day of spring. No clouds. No shadows. No doubt.

She was at her favorite spot in the world, an escarpment just beyond the edge of town. She had been watching the sunlight break into fragments on the ocean waves.

She had just decided to go home when a strap on her sandal snapped. He happened to be nearby to help.

He fell in love with her as soon as he saw her. Tamiya's clearly defined features and his kindness immediately attracted her as well. But Oiwa's family did not approve. He was without a retainer and had squandered most of his savings by living beyond his means. His weakness was that he loved beautiful things. And she was truly beautiful.

When they walked together down the street, passersby could not help but admire their appearance. When they stood next to a cherry tree, Tamiya saw that they enhanced the blossoms' loveliness. Oiwa's beauty complemented his own wonderfully.

Her parents finally relented and provided the very handsome dowry they had been saving since the day she was born. She and Tamiya could not have been happier. They were married in early summer, after the rains lifted.

Their life together started blissfully. They shared each other's joys and hopes, and learned what gave each other pleasure. They became intimate with each other's habits and bodies. And each discovery filled them with delight.

But the days and weeks drifted by without incident. Perhaps if they had met with exceptional fortuneÂ

â

or even misfortuneÂ

â

this might have distracted Tamiya. As it was, his mind was idle and therefore prone to needless wanderings. His new bride's timid laughterÂ

â

which just the previous week had filled him with blissÂ

â

now bored and even annoyed him.

He began to notice small creases at the corners of her lips and eyelids. She may as well have been wilting before his eyes. Tamiya could envision too easily how his wife would look in five, ten and twenty years. Her transformation in his mind's eye was shocking. He marveled at how he could not have seen this before their marriage.

And because he would never imagine himself growing old, Tamiya felt unfairly burdened by Oiwa's mortality. He was determined to think of his life as joyless, so it of course became that way. He took to spending hours in his favorite diner, drinking copious amounts of rice wine, eating and making lewd remarks at the waitresses.

He staggered home several times a week, the front of his kimono stained and hanging open. Oiwa watched helplessly as he stumbled in through the door and crawled about the halls, shouting obscenities before falling into a noisy sleep.

Once or twice, she gently asked what was bothering him. Each time Tamiya loudly proclaimed she was all that was wrong with his life, before drawing his sword and pointing it at her menacingly. She was too frightened to try again.

His wife's passivity at once amused and irritated Tamiya. He drank more and spent more, as if this salved a burning in his heart. He could not see that he was mistaking his own cruelty for misery.

One night, a ragged voice called him from behind as he drank.

“Tamiya-san!”

He turned to find one of his moneylenders, a haggard old man whose upper front teeth were missing.

“Itoh,” Tamiya spat. “What do you want? I paid you back everything I owed.”

“Is that any way to greet an old friend?” Itoh chuckled. “I haven't seen you since you were married. I thought I would come over and buy you a drink.”

Tamiya looked at Itoh's wrinkled face suspiciously. The old man was a rice vendor who provided high-interest loans on the sideÂ

â

a hobby in which he took cruel pleasure.

Tamiya decided accepting one drink could not do any harm.

“How is married life?” Itoh asked as he poured sake into Tamiya's cup. “Pardon me for saying, but you are far luckier than you deserve. A beautiful wife. A dowry with which to settle your debts. And you have enough left over to drink here every night without a care.”

“I'm not here every night.”

“That's not what I hear, Tamiya-san.”

As Tamiya thought about this, Itoh poured more sake.

“My granddaughter asks about you all the time.”

“Ume?”

“Oh, yes. Ironic, isn't it? She could not spare you a simple hello when you came to borrow money. But now she hears you're doing well, and she wonders when you're going to grace us again with your presence.”

Tamiya thought about Itoh's granddaughter. Her cheeks were as red as apples, and her eyes were big and round. Her skin was without a blemish, and on the rare occasion when she spared him a smile, everything around her seemed to smile also.

“It's a shame,” said Itoh. “Now with your newfound fortune, I would not object to you two getting together.”

Tamiya was momentarily confused, but quickly realized he should be indignant.

“How dare you! I am a happily married man!”

“Oh, yes. So happily married that you spend most nights here drinking alone.”

“I don't have to listen to this.” Tamiya stood up as abruptly as he could. He almost fell over.

“Just think about it,” said Itoh. “Nothing more. Think about starting over with a younger woman. I know ways in which your present life, along with your wife, can be put completely behind you.”

Tamiya hesitated.

“Go on now,” Itoh said. “I'll take care of the bill.”

The air was brisk against Tamiya's face as he walked home. He could not stop thinking about the moneylender. Could Ume truly be thinking about him after all this time? Tamiya grew increasingly intrigued with each step he took. He walked faster without realizing it.

At home he found Oiwa cheerier than usual, waiting for him with more sake and food. Tamiya felt his back stiffen when he saw her. She smiled warmly and took his hand, leading him to his cushion on the floor. She poured him a cup of sake.

“I am so glad you're here,” she said. “I have some good news.”

“What is it?” he asked.

She looked at the floor, wondering how best to phrase her surprise.

Finally, she simply blurted, “I'm pregnant!”

Tamiya felt blood rush from his face. A child? In this house? A child who would cry endlessly and demand all his attention? Did Oiwa not realize he had no more of himself to give?

She had no way of knowing what was going through his mind. In fact, she had been overjoyed when he came home early, for this was an auspicious sign. She was sure a child was all they needed to help straighten his ways. She even imagined him getting a job. Anything that would provide a modest income would do. She hummed as she spooned him a bowl of rice.

Tamiya looked at his wife's belly. This would soon swell like a bale of rice, he knew. How would they appear when they walked out on the town together? What would people say?

He thought of UmeÂ

â

young and always thinking of him.

“Are you not eating?” Oiwa asked.

â¢

The sun burned brightly the next day. Tamiya made his way to the rice shop old Itoh managed.

As always in mid-morning, delivery men rushed in and out of the store. Young clerks helped keep the orders straight while Itoh barked instructions from the rear.

Tamiya felt himself disappear in the commotion. A part of him wanted to remain invisible.

But the old man's eyesight was as good as ever. He grinned and waved.

“I'm glad to see you!” said Itoh. “Are you here to buy rice or borrow money?”

Tamiya glared at him, which made the rice vendor cackle.

“Such a fearful face! Where's your sense of humor?”

Tamiya looked around and said in a low voice, “Oiwa is pregnant.”

To Tamiya's surprise, Itoh seemed genuinely dismayed.

“I see,” he said, sighing. The old man led Tamiya to a quiet courtyard behind the store.

“You said you knew of a way for me to leave my marriage?” Tamiya asked.

Itoh looked as solemn as the world's end.

“Yes,” he said. “Indeed I said that. But you will need to be very determined. Now more than ever.”

“I am!” Tamiya hissed. “I don't want a child! Can you imagine how much trouble that would be?”

“Are you absolutely sure?” But as soon as he asked the question, Itoh knew the answer. He had seldom seen determination as steadfast as what was behind Tamiya's twisted face.

“Wait here, and I will be right back.”

The old man went into the dark hall and emerged a moment later. He was holding something in his closed fist. He looked around to make certain no one was nearby.

“I've been using this to keep the rats from getting in the rice.”

He handed Tamiya a small white packet.

“Poison?” Tamiya asked, suddenly afraid.

“It's the most reliable way. I don't see you as physically capable of killing anyone. This way, you add it to her tea and it will be instantaneous. You just have to get rid of the body later.”

Tamiya's hands started to shake. He nodded vigorously.

“Are you sure you wish to do this?”

Tamiya hesitated for a moment, then nodded again.

â¢

“Water!”

Oiwa pleads with him. The flame dances on the candlewick. His hands have not stopped shaking since the morning.

Why is this taking so long?

Tamiya rushes to get a cup of water. As she takes it from his hands, he thinks of a convenient reason to leave.

“Wait here, my love,” he says earnestly. “I will run and get a doctor.”

“Don't leave me.”

“I must.” He pries her fingers off his hand.

He rushes out onto the dark empty street and away from the house. When the light spilling from his front entrance is out of sight, he slows to a walk.

He has to think. How long should he take to return with the doctor? What would be a respectable amount of time? Will the poison have done its job by then?

He drags his feet to the doctor's clinic.

He manages to feign urgency once the doctor appears at his door. They rush back to his house, where Tamiya is shocked to find Oiwa still alive, moaning in agony. There is blood and vomit on the floor. Tamiya has more than enough reason to feel faint.

They carry her upstairs, where he lays out a futon. Oiwa reaches for her husband's hand, and she does not let go the entire time the doctor is examining her. Sometimes she flinches in pain, digging her nails into Tamiya's skin. He bites his lip.

“This seems to be a very bad case of food poisoning. You must have ingested something spoiled. Fish, maybe,” the doctor tells her. “You are lucky to be alive.”

“The baby?” Oiwa asks, although she knows the answer.

The doctor shakes his head. The tears flow freely, and she can hardly see the expression on Tamiya's face.

â¢

The sun never stops shining, no matter how terribly we behave.

Days later, Oiwa notices that the mirror that usually stands in the corner of the room is not there. She calls out for Tamiya.

There is no answer. Her hair is unwashed. She must look a mess.

She manages nonetheless to make her way downstairs. Her legs are stiff, and the floor tilts to one side, then the other. No one is in the house. The air is cool and soothing.

She manages to find the mirror stand, which someone has brought downstairs. It is in the sitting room, and there is enough light to see.

Enough to see the sores all over her pale skin, dry scabs forming across the bruises. Enough to see her scalp bare, aside from the few strands left of her once silken hair, now wiry and shimmering with grease. Enough to see how her face has swollen and hardened, with a ridiculously large sty above one eye.

She screams, just as she did that night. She screams, begging for mercy in an empty house. She screams, over and over, into the cold darkness.

â¢

Tamiya can hardly look at his wife, but he is determined to be kind. They are already whispering in the streets.

He was drinking every night, they say. He was clearly not happy in his marriage. How might he have reacted to news of her pregnancy?

Fortunately, the doctor pronounced it food poisoning. There had been similar cases in town recently.

Still, Tamiya knows he now has to be conspicuously caring. He goes out daily to shop for food and medicine. He does all the cooking and tries his best to keep the house clean.

Time and again, he finds himself exhausted at the end of the day, only to have Oiwa calling for him with another demand. More water. Rub her shoulder. It's time for her medicine.

Time and again, he is barely able to contain his anger.

It does not help that Oiwa is obviously able to do much herself. She frequently comes downstairs and sits in front of the mirror. She tilts her head to one side as if fascinated by her own disfigurementÂ

â

one eye shut completely under the sty, the other sunken and bloodshot. Once she smiles faintly, as if she is looking at someone else.

She regains more strength and asks him to take her for walks. Anger flares in his belly, but his smile betrays nothing. He only mildly cautions her that she should not overly strain herself. When neighbors wave hello or congratulate Oiwa on her recovery, he avoids their gaze.