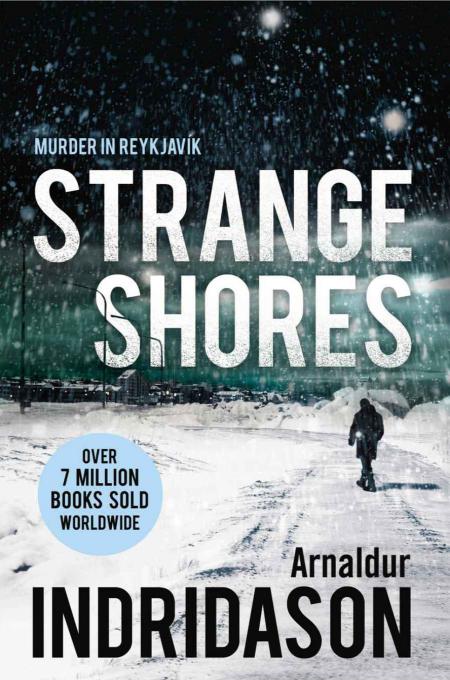

Strange Shores

Contents

A young woman walks into the frozen fjords of Iceland, never to be seen again. But Matthildur leaves in her wake rumours of lies, betrayal and revenge.

Decades later, somewhere in the same wilderness, Detective Erlendur is on the hunt. He is looking for Matthildur but also for a long-lost brother, whose disappearance in a snow-storm when they were children has coloured his entire life. He is looking for answers.

Slowly, the past begins to surrender its secrets. But as Erlendur uncovers a story about the limits of human endurance, he realises that many people would prefer their crimes to stay buried.

Arnaldur Indriðason worked for many years as a journalist and critic before he began writing novels. Outside Iceland, he is best known for his crime novels featuring Detectives Erlendur and Sigurdur Óli, which are consistent bestsellers across Europe. The series has won numerous awards, including the Nordic Glass Key – an award also won by Scandinavian crime authors, Henning Mankell and Jo Nesbo – and the CWA Gold Dagger.

IN ENGLISH TRANSLATION

TAINTED BLOOD

(FIRST PUBLISHED WITH THE TITLE

JAR CITY

)

SILENCE OF THE GRAVE

VOICES

THE DRAINING LAKE

ARCTIC CHILL

HYPOTHERMIA

OPERATION NAPOLEON

OUTRAGE

BLACK SKIES

Arnaldur Indriðason

TRANSLATED FROM THE ICELANDIC BY VICTORIA CRIBB

May my poem pass like a breeze through the sedge by the Styx, its singing bring solace, lull to sleep those who wait.

Snorri Hjartarson

HE NO LONGER

feels cold: instead, a curious heat is spreading through his veins. He had thought there was no warmth left in his body but now it is flooding into his limbs, bringing a sudden flush to his face.

He is lying flat on his back in the dark, his thoughts wandering and confused, only dimly aware of the borderline between sleep and waking. It is terribly hard to concentrate, to grasp what is happening to him. His consciousness ebbs and flows. He doesn’t feel unwell, just pleasantly drowsy, visited by a procession of dreams, visions, sounds and places, all familiar, yet somehow strange. His mind plays odd tricks on him, shuttling back and forth between past and present, through time and space, and there is little he can do to control its shifts. One minute he is sitting at his mother’s hospital bedside as she slips away; the next, he is plunged into the black depths of winter and senses that he is still lying on the floor of the derelict farmhouse that was once his home. But this must be an illusion.

‘Why are you lying here?’

Raising his head, he perceives a figure standing in the doorway.

A traveller must have found his way into the house. He doesn’t understand the question.

‘Why are you lying here?’ the traveller asks again.

‘Who are you?’ he answers.

He can’t see the man’s face, didn’t hear him enter. All he can make out is his silhouette. The man keeps repeating the same needling question over and over again.

‘Why are you lying here?’

‘I live here. Who are you?’

‘I’m going to stay with you tonight, if I may.’

Then the man is sitting beside him on the floor and appears to have lit a fire. Sensing the warmth on his face, he reaches towards the blaze. Only once before has he experienced such intense cold.

‘Who are you?’ he asks for the third time.

‘I came to listen to you.’

‘To listen to me? Who’s that with you?’

They are not alone; there is an invisible presence beside the man.

‘Who’s that with you?’ he asks again.

‘No one,’ says the traveller. ‘I’m alone. Was this your home?’

‘Are you Jakob?’

‘No, I’m not Jakob. Extraordinary that the walls should still be standing. The house must have been well built.’

‘Who are you? Are you Bóas?’

‘I was just passing.’

‘Have you been here before?’

‘Yes.’

‘When?’

‘Many years ago, when there were people still living here. Do you know what became of them – the family who used to live here?’

Now he is immobile in the dark, unable to move for the cold. He is alone again: the fire and the derelict farmhouse have vanished. He is shrouded in freezing darkness, and the warmth is leaching from his face, hands and feet.

Again he hears a scraping noise.

It is approaching from some remote, cold distance, growing ever louder, accompanied by piercing wails of anguish.

HE STOOD IN

the drizzle by the crags at Urdarklettur, watching as a hunter picked his slow way towards him. They exchanged polite greetings, their words shattering the silence as if broadcast from an alien world.

The sun had not broken through the clouds for several days. Fog lay in a heavy cloak over the fjords and the forecast was for falling temperatures and snow. Nature had sunk into its winter torpor. The hunter asked what he was doing up there; no one went on to the moors these days except a few old-timers like him, culling foxes. He tried to sidestep the question by replying that he was from Reykjavík. The hunter remarked that he had spotted somebody down at the deserted property by the fjord.

‘That was probably me.’

The hunter did not pursue the matter but said he had a farm nearby and was out on his own today. ‘What’s your name?’ he asked.

‘Erlendur.’

‘I’m Bóas.’ They shook hands. ‘There’s a sheep-worrier living in the rocks higher up; a real pest. It’s attacked a lot of stock recently.’

‘A fox?’

Bóas rubbed his jaw. ‘I caught it skulking around the sheep sheds the other day. Got one of my lambs. Put the wind up the entire flock.’

‘And you say it has a lair up here?’

‘I saw it make off this way. I’ve seen it a couple of times now, so I reckon I know where its earth is. Are you heading up to the moor? Don’t mind if you keep me company.’

He hesitated, then nodded. The farmer seemed content with that; no doubt he would be glad of the conversation. He had a rifle slung over one shoulder and an ammunition belt and worn leather satchel over the other. Under them he was wearing a shabby anorak and dull-green waterproof trousers. He was a vigorous little man, though he must have been well into his sixties. His head was bare and a thick mop of hair hung over his forehead, obscuring a beady pair of eyes. His nose was flattened and bent, as if broken long ago and never properly set, and his mouth was concealed by an unkempt beard apart from when he opened it to talk – he was a chatty fellow and had opinions on everything under the sun. Yet he tactfully refrained from asking Erlendur too much about his movements or why he had chosen to stay in the ruined croft at Bakkasel.

Erlendur had made himself at home in the old house. The roof was still fairly intact, though not watertight, and the rafters were rotten but he had managed to find a dry patch on the floor in what had once been the sitting room. It had started to rain and gust a couple of days ago, and the wind howled around the bare walls, yet they did provide shelter against the wet and he was cosy enough thanks to the gas lantern which he kept on a low flame to eke out the canister. The lamp cast a dim glow where he sat, but all around him the night closed in, black as the inside of a coffin.

At one time the house and land had ended up in the hands of a bank, but Erlendur had no idea who owned them now. In any case no one had ever complained about his camping there on his trips out east. He didn’t have much luggage. The rental car was parked out the front, a blue SUV, whose jeep-like appearance belied the heavy weather it had made of the drive up to the house. The track had almost disappeared, overgrown by vegetation that never used to be there. Little by little nature was conspiring to merge the property into its surroundings, gradually obliterating all traces of human habitation.

Visibility grew steadily worse as he and Bóas gained height, until they were enclosed on all sides by milk-white cloud. Once they reached the tops the drizzle gave way to light rain and their feet left a trail on the damp ground. The hunter listened for bird calls and cast around for his quarry’s tracks in the wet grass. Erlendur tramped behind in silence. He had never lain in wait by a fox’s earth, never stalked an animal or fished a river or lake, let alone felled any larger prey like reindeer. Bóas seemed to read his mind.

‘Not a hunting man yourself?’ he asked, pausing for a brief rest.

‘No.’

‘Don’t mind me – it’s the way I was brought up.’ Bóas opened his leather satchel, offered Erlendur some dark rye bread and sliced off a hunk of hard mutton pâté to go with it. ‘I mainly go after the foxes these days, to keep the numbers down. The little buggers are getting bolder by the day, though personally I’ve nothing against them. They’ve as much right to live as any other creature. But you have to keep them away from the stock – harmony in everything.’

They ate the rye bread. The pâté was very good and he guessed it was probably home-made. Having failed to bring any supplies himself, he had nothing to contribute to the meal. He didn’t really know why he had accepted this unsought but civil invitation. Maybe it was a desire for human contact. He had hardly seen a soul for days, and it occurred to him that the same was probably true of this man Bóas.

‘What do you do down there in the city?’ asked the farmer.

He didn’t answer immediately.

‘Sorry, I’m such a nosy bastard.’

‘No, it’s all right,’ he replied. ‘I’m a policeman.’

‘That can’t be much fun.’

‘No. Though it has its moments.’

They climbed on higher to the moor, and he took care to tread lightly on the heather. From time to time he stooped to brush his hand over the low-growing vegetation, trying to remember if he had ever heard of Bóas as a child. The name didn’t ring any bells, though that was hardly surprising – he had lived in the east for a comparatively short period and lost touch with the area after moving to the city. Anyway, guns had been a rare sight in his home. He vaguely recalled a passer-by at his parents’ house who had stopped to speak to his father, gesturing down the river with a rifle in his hand. And he remembered that his uncle, his mother’s brother, had owned a jeep and used to shoot reindeer. He had worked as a ghillie for city dwellers who came out east to bag a deer, and would bring his family the meat. The fried steaks were a real treat. But he couldn’t remember anyone hunting foxes, nor a farmer named Bóas.