Striding Folly (5 page)

But the bells of Fenchurch St. Paul’s in

Nine Tailors

with Lord Peter ringing at No. 2 will last as long as people read:

The bells gave tongue: Gaude, Sabaoth, John, Jericho, Jubilee, Dimity, Batty Thomas and Tailor Paul, rioting and exulting high up in the dark tower, wide mouths rising and falling, brazen tongues clamouring, huge wheels turning to the dance of the leaping ropes. Tin tan dan din bo bim bom . . . every bell in her place striking tuneably, hunting up, hunting down, dodging, snapping, laying her blows behind, making her thirds and fourths, working down to lead the dance again. Out over the flat white wastes of fen, over the spear-straight steel dark dykes and the wind bent groaning poplar trees, bursting from the snow-choked louvres of the belfry, whirled away southward and westward in gusty blasts of clamour to the sleeping counties went the music of the bells – little Gaude, silver Sabaoth, strong John and Jericho, glad Jubilee, sweet Dimity and old Batty Thomas, with great Tailor Paul bawling and striding like a giant in the midst of them. Up and down went the shadows of the ringers on the walls, up and down went the scarlet sallies, roofwards and floorwards, and up and down hunting in their courses, went the bells of Fenchurch St. Paul.

Very nice, you might say, but what has all this to do with solving the mystery of a faceless and handless corpse in a grave belonging to someone else?

Well that’s just it, it has everything to do with it.

Janet Hitchman

1972

Striding Folly

A LORD PETER WIMSEY STORY

‘Shall I expect you next Wednesday for our game as usual?’ asked Mr Mellilow.

‘Of course, of course,’ replied Mr Creech. ‘Very glad there’s no ill feeling, Mellilow. Next Wednesday as usual. Unless . . .’ his heavy face darkened for a moment, as though at some disagreeable recollection. ‘There may be a man coming to see me. If I’m not here by nine, don’t expect me. In that case, I’ll come on Thursday.’

Mr Mellilow let his visitor out through the french window and watched him cross the lawn to the wicket gate leading to the Hall grounds. It was a clear October night, with a gibbous moon going down the sky. Mr Mellilow slipped on his goloshes (for he was careful of his health and the grass was wet) and himself went down past the sundial and the fish-pond and through the sunk garden till he came to the fence that bounded his tiny freehold on the southern side. He leaned his arms on the rail and gazed across the little valley at the tumbling river and the wide slope beyond, which was crowned, at a mile’s distance, by the ridiculous stone tower known as the Folly. The valley, the slope and the tower all belonged to Striding Hall. They lay there, peaceful and lovely in the moonlight, as though nothing could ever disturb their fantastic solitude. But Mr Mellilow knew better.

He had bought the cottage to end his days in, thinking that here was a corner of England the same yesterday, today and for ever. It was strange that he, a chess-player, should not have been able to see three moves ahead. The first move had been the death of the old squire. The second had been the purchase by Creech of the whole Striding property. Even then, he had not been able to see why a rich business man – unmarried and with no rural interests – should have come to live in a spot so remote. True, there were three considerable towns at a few miles’ distance, but the village itself was on the road to nowhere. Fool! he had forgotten the Grid! It had come, like a great, ugly chess-rook swooping from an unconsidered corner, marching over the country, straddling four, six, eight parishes at a time, planting hideous pylons to mark its progress, and squatting now at Mr Mellilow’s very door. For Creech had just calmly announced that he was selling the valley to the Electrical Company; and there would be a huge power-plant on the river and workmen’s bungalows on the slope, and then Development – which, to Mr Mellilow, was another name for the devil. It was ironical that Mr Mellilow, alone in the village, had received Creech with kindness, excusing his vulgar humour and insensitive manners, because he thought Creech was lonely and believed him to be well-meaning, and because he was glad to have a neighbour who could give him a weekly game of chess.

Mr Mellilow came in sorrowful and restored his goloshes to their usual resting-place on the verandah by the french window. He put the chessmen away and the cat out and locked up the cottage – for he lived quite alone, with a woman coming in by the day. Then he went up to bed with his mind full of the Folly, and presently he fell asleep and dreamed.

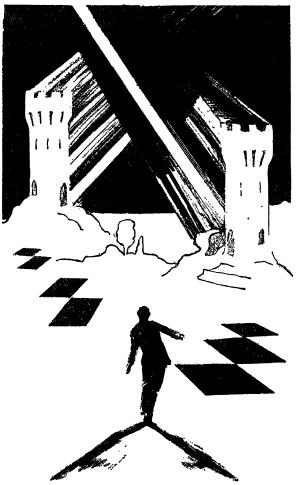

He was standing in a landscape whose style seemed very familiar to him. There was a wide plain, intersected with hedgerows, and crossed in the middle distance by a river, over which was a small stone bridge. Enormous blue-black thunderclouds hung heavy overhead, and the air had the electric stillness of something stretched to snapping point. Far off, beyond the river, a livid streak of sunlight pierced the clouds and lit up with theatrical brilliance a tall, solitary tower. The scene had a curious unreality, as though of painted canvas. It was a picture, and he had an odd conviction that he recognised the handling and could put a name to the artist. ‘Smooth and tight,’ were the words that occurred to him. And then: ‘It’s bound to break before long.’ And then: ‘I ought not to have come out without my goloshes.’

It was important, it was imperative that he should get to the bridge. But the faster he walked, the greater the distance grew, and without his goloshes the going was very difficult. Sometimes he was bogged to the knee, sometimes he floundered on steep banks of shifting shale; and the air was not merely oppressive – it was

hot

like the inside of an oven. He was running now, with the breath labouring in his throat, and when he looked up he was astonished to see how close he was to the tower. The bridge was fantastically small now, dwindled to a pin-point on the horizon, but the tower fronted him just across the river, and close on his right was a dark wood, which had not been there before. Something flickered on the wood’s edge, out and in again, shy and swift as a rabbit; and now the wood was between him and the bridge and the tower behind it, still glowing in that unnatural streak of sunlight. He was at the river’s brink, but the bridge was nowhere to be seen – and the tower, the tower was moving. It had crossed the river. It had taken the wood in one gigantic leap. It was no more than fifty yards off, immensely high, shining, and painted. Even as he ran, dodging and twisting, it took another field in its stride, and when he turned to flee it was there before him. It was a double tower – twin towers – a tower and its mirror image, advancing with a swift and awful stealth from either side to crush him. He was pinned now between them, panting. He saw their smooth, yellow sides tapering up to heaven, and about their feet went a monstrous stir, like the quiver of a crouching cat. Then the low sky burst like a sluice and through the drench of the rain he leapt at a doorway in the foot of the tower before him and found himself climbing the familiar stair of Striding Folly. ‘My goloshes will be here,’ he said, with a passionate sense of relief. The lightning stabbed suddenly through a loop-hole and he saw a black crow lying dead upon the stairs. Then thunder . . . like the rolling of drums.

The daily woman was hammering upon the door. ‘You

have

slept in,’ she said, ‘and no mistake.’

Mr Mellilow, finishing his supper on the following Wednesday, rather hoped that Mr Creech would not come. He had thought a good deal during the week about the electric power scheme, and the more he thought about it, the less he liked it. He had discovered another thing which had increased his dislike. Sir Henry Hunter, who owned a good deal of land on the other side of the market town, had, it appeared, offered the Company a site more suitable than Striding in every way on extremely favourable terms. The choice of Striding seemed inexplicable, unless on the supposition that Creech had bribed the surveyor. Sir Henry voiced his suspicions without any mincing of words. He admitted, however, that he could prove nothing. ‘But he’s crooked,’ he said; ‘I have heard things about him in Town. Other things. Ugly rumours.’ Mr Mellilow suggested that the deal might not, after all, go through. ‘You’re an optimist,’ said Sir Henry. ‘Nothing stops a fellow like Creech. Except death. He’s a man with enemies . . .’ He broke off, adding, darkly, ‘Let’s hope he breaks his damned neck one of these days – and the sooner the better.’

Mr Mellilow was uncomfortable. He did not like to hear about crooked transactions. Business men, he supposed, were like that; but if they were, he would rather not play games with them. It spoilt things, somehow. Better, perhaps, not to think too much about it. He took up the newspaper, determined to occupy his mind, while waiting for Creech, with that day’s chess problem. White to play and mate in three.

He had just become pleasantly absorbed when a knock came at the door front. Creech? As early as eight o’clock? Surely not. And in any case, he would have come by the lawn and the french window. But who else would visit the cottage of an evening? Rather disconcerted, he rose to let the visitor in. But the man who stood on the threshold was a stranger.

‘Mr Mellilow?’

‘Yes, my name is Mellilow. What can I do for you?’

(A motorist, he supposed, inquiring his way or wanting to borrow something.)

‘Ah! that is good. I have come to play chess with you.’

‘To play chess?’ repeated Mr Mellilow, astonished.

‘Yes; I am a commercial traveller. My car has broken down in the village. I have to stay at the inn and I ask the good Potts if there is anyone who can give me a game of chess to pass the evening. He tells me Mr Mellilow lives here and plays well. Indeed, I recognise the name. Have I not read

Mellilow on Pawn-Play

? It is yours, no?’

Rather flattered, Mr Mellilow admitted the authorship of this little work.

‘So. I congratulate you. And you will do me the favour to play with me, hey? Unless I intrude, or you have company.’

‘No.’ said Mr Mellilow. ‘I am more or less expecting a friend, but he won’t turn up till nine and perhaps he won’t come at all.’