Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (16 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

Haghia Eirene was almost destroyed in the year 564, when a fire ruined the atrium and part of the narthex, but it was soon afterwards repaired by Justinian, then in the last year of his life. In October 740 the church was severely shaken by a violent earthquake and was once again restored, either by Leo III or his son Constantine V. It appears that since that date no further major catastrophe has befallen the church, so that the building we see today is essentially that of Justinian, except for the eighth-century repairs and minor Turkish additions. After the Conquest, Haghia Eirene was enclosed within the outer walls of Topkap

ı

Saray

ı

. The outermost court of the Saray, where Haghia Eirene was located, was principally given over to the Janissaries and the church was used by them as an arsenal. Later, some years after the destruction of the Janissaries in 1826, Haghia Eirene became a storehouse for antiquities, principally old Ottoman armaments. Beginning in the 1950s, the interior of Haghia Eirene was cleared of its military exhibits and thoroughly restored, and since then it has been used for concerts and exhibitions.

The ground around the church has risen some five metres above its ancient level and the present entry is through a Turkish porch and outbuildings towards the western end of the north aisle. Entering the church, we descend in semi-darkness along a stone ramp to the level of the interior. At the end of the ramp we pass through the north aisle and find ourselves at the rear of the church, looking down the length of the nave. From here we can see that the church is a basilica, but a basilica of a very unusual type. The wide nave is divided from the side aisles by the usual columned arcade, but this arcade is interrupted towards the west by the great piers that support the dome to the east and the smaller elliptical domical vault to the west. The eastern dome is supported by four great arches which are expanded into deep barrel-vaults on all sides except the west. Here we see the transition from a pure domed basilica to a centralized Greek-cross plan, which was later to supersede the basilica. The apse, semicircular within, five-sided without, is covered by a semidome. Below there is a synthronon, the only one in the city surviving from Byzantine times; this consists of six tiers of seats around the periphery of the apse facing the site of the altar, with an ambulatory passage beneath the top row, entered through framed doorways on either side.

In the semidome of the apse there is an ancient mosaic of a simple cross in black outline standing on a pedestal of three steps, against a gold ground with a geometric border. The inscription here is from Psalm lxv, 4 and 5; that on the bema arch perhaps from Amos ix, 6, with alterations, but in both cases, parts of the mosaic have fallen away and the letters were painted in by someone who was indifferent both to grammar and sense. There is some difference of opinion concerning the dating of these mosaics, one opinion being that they are to be ascribed to the reconstruction by Constantine V after the earthquake of 740, the other holding that they are from Justinian’s time. The decorative mosaics in the narthex, which are not unlike those in Haghia Sophia, are almost certainly from Justinian’s period.

At the western end of the nave, five doors lead from the church into the narthex and formerly five more led thence into the atrium, but three have been blocked up. This atrium and the scanty remains of that at St. John of Studius (see Chapter 16) are the only ones that are now extant in the city. Unfortunately, the one here has been rather drastically altered, for the whole of the inner peristyle is Turkish as well as a good many bays of the outer. But most of the outward walls are Byzantine; and curiously irregular they are, the northern portico being considerably longer than the southern so that the west wall runs at an angle. In the south-east corner, a short flight of steps leads to a door that communicated with buildings to the south, the ruins of which will be described presently. Haghia Eirene now serves as a concert hall for many of the musical events produced in the Istanbul International Festival; it makes a superb setting for these performances, and the acoustics of the old church are excellent.

If we leave Haghia Eirene and walk back through the garden behind the apse we can examine the ruins to the south of the church. (These are obscured by a fence and are not officially open to the public, but one can still view the ruins discretely.) These ruins, which were first excavated in 1946, are almost certainly the remains of the once-famous Hospice of Samson. Procopius informs us that between Haghia Sophia and Haghia Eirene “there was a certain hospice, devoted to those who were at once destitute and suffering from serious illness, namely those who were suffering the loss of both property and health. This was erected in early times by a certain pious man, Samson by name.” Procopius then goes on to say that the Hospice of Samson was destroyed by fire during the Nika Revolt, along with the two great churches on either side of it, and that it was rebuilt and greatly enlarged by Justinian. Unfortunately, the excavations were never carried far enough to make clear the plan of the Hospice. One can make out a courtyard opposite the atrium of Haghia Eirene, where some columns and capitals (which don’t seem to fit) have been set up again. To the east is a complex series of rooms, including a nympheaeum and a small cistern, some of them with

opus sectile

floors. There is a broad corridor between the Hospice and Haghia Eirene and to the east a vaulted ramp which may have given access to the galleries of the church. From the masonry and the capitals it would appear that the major part of the work is of the time of Justinian and doubtless belongs to the reconstruction mentioned by Procopius. It is clear that this building connected directly with the atrium of Haghia Eirene, which is only a few feet higher than the level of the courtyard. One may hope that more serious and competent excavations will soon be carried out.

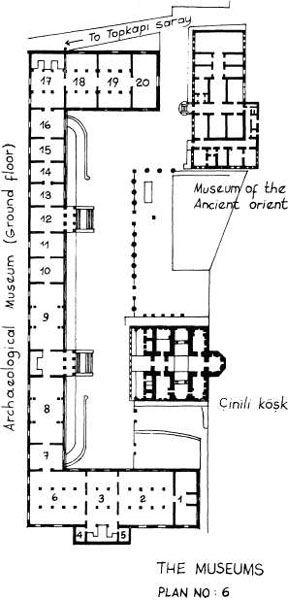

We now leave the precincts of Haghia Eirene and take the path which leads to the gate on the left side of the First Court. The building complex to the left of the gate is the Darphane, the former Imperial Mint and Treasury. This has been restored and is now open to the public; there is little of great interest to be seen except when there are special exhibitions or cultural events. At the lower entrance to the Darphane we see on the right the general entrance to the Archaeological Museum, the Museum of the Ancient Orient and the Çinili Kö

ş

k.

As we enter the courtyard the first building on our left is the Museum of the Ancient Orient. The entrance to the museum is flanked by two basalt lions of the neo-Hittite period (ca. 800 B.C.). The museum houses a unique collection of pre-Islamic Arab artifacts mostly from the Yemen, along with Babylonian, Neo-Hittite and Assyrian antiquities, including a series of the superb faience panels of lions and monsters, yellow on a blue ground, that once adorned the processional way to the Isthar gate at Babylon. Notable exhibits include the statue of a deified Babylonian king from the beginning of the second millennium B.C.; inscribed tablets with the Code of Hammurabi (1750 B.C.) and the Treaty of Kadesh (1286 B.C.); reliefs and colossal statues of the neo-Hittite period; a small Egyptian collection; and a selection of cuneiform cylinders for which the museum is famous. The collection as a whole is not large but is of the greatest historical importance. The building has recently been restored and the collection reorganized, thus making this one of the most interesting and attractive museums of antiquities in Europe.

THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL MUSEUM

The Archaeological Museum occupies the whole right side and far end of the courtyard. The modern history of the museum can be said to date from 1881, when Osman Hamdi Bey was made director. Over the next three decades, until his death in 1910, Osman Hamdi Bey succeeded in establishing the modern institution which we see today, one of the great museums of Europe. One of the most dramatic events in this development came in 1887 during Osman Hamdi Bey’s excavation of the royal necropolis at Sidon, when he unearthed the magnificent group of sarcophagi which are the pride of the museum. Since the Çinili Kö

ş

k, where antiquities were first stored, proved too small to house these new acquisitions, a new museum was built directly opposite and opened to the public in 1896. Later discoveries by Osman Hamdi Bey and other archaeologists soon filled this museum to overflowing and it became necessary to build two additional wings, which were opened in 1902 and 1908. A new four-storey annexe was begun behind the museum in 1988 and completed in 1992.

On entering the museum notice the colossal porphyry sarcophagi arrayed along the side of the building between the two stairways. These contained the remains of early Byzantine emperors of the fourth and fifth centuries and were originally in the crypt of the church of the Holy Apostles on the Fourth Hill, now the site of Fatih Camii (see Chapter 12).

On entering from the first stairway we will first turn left to see the exhibits in the northern half of the museum; after which we will then retrace our steps to see the southern half; we will then go on to look at the antiquities in the annexe, whose entrance is opposite the museum shop between the two stairways. In the lobby we see a colossal statue of Bes, the Cypriot Hercules, holding up a headless lioness by her hind paws. A great hole gapes from the god’s loins; it has been politely suggested that this once served as a fountain, but it was perhaps more likely the seat of an appropriately gigantic phallus. The statue is from Cyprus and dates from the imperial Roman era, first to third century A.D.

The first two rooms beyond the museum shop contain a number of the extraordinary sarcophagi discovered by Osman Hamdi Bey in the royal necropolis at Sidon in Syria. These sarcophagi belonged to a succession of kings who ruled in Phoenicia between the mid-fifth century B.C. and the latter half of the following century. Just inside the doorway of the first room we see the Tabit Sarcophagus, made in the sixth century B.C. for an Egyptian general and reused in the following century by Tabnit, King of Sidon, whose remains are displayed in the glass case just beyond. Also on exhibit here are the Lycian Sarcophagus and the Satrap Sarcophagus, both from the latter part of the sixth century B.C. and found in the region known as Lycia on the Mediterranean coast of Turkey. Beyond these rooms is the lobby inside the second staircase, which is devoted to Osman Hamdi Bey, with photographs illustrating his career.

The next room exhibits some of the sarcophagi discovered at Sidon by Osman Hamdi Bey in 1887. The most famous of these is the magnificent Alexander Sarcophagus, so-called not because it is that of Alexander himself (as is so often said), but because it is adorned with sculptures in deep, almost round relief showing Alexander in scenes of hunting and war. The sarcophagus was made for King Abdalonymos of Sidon, who began his reign in 333 B.C. after Alexander defeated the Persians at the battle of Issus, which may be represented in the reliefs of battle scenes on the sarcophagus. Also exhibited here are two other outstanding funerary monuments, the Satrap Sarcophagus and the Sarcophagus of Mourning Women. The Satrap Sarcophagus, which is dated to the second half of the fifth century B.C., takes its name from the fact that it was the tomb of a satrap, or Persian viceroy, who is shown reclining on a couch in a relief on one side of the monument, while on the other side he appears in a hunting scene. The Sarcophagus of Mourning Women dates from mid-fourth century B.C. It takes its name from the statues of the mourning women framed between Ionic columns on its sides and ends, 18 in all. A funeral procession is shown in a frieze on the lid of the sarcophagus, which is thought to have belonged to King Straton of Sidon, who died in 360 B.C.

The rooms beyond are principally devoted to sarcophagi and other funerary monuments, the finest of which are perhaps the Meleager Sarcophagus, the Sarcophagus of Phaedra and Hippolytus, and the Sidamara Sarcophagus, which date from the third and second centuries B.C. Other outstanding exhibits include reliefs from two Hellenistic temples in western Asia Minor, the temple of Hecate at Lagina and the temple of Artemis at Magnesia on the Maeander. The two stone lions which flank the foot of the staircase once stood on the façade of the Byzantine palace of Bucoleon (see Chapter 6), and were removed to the museum during the construction of the railway line along the Marmara in 1871.

Returning to the entrance lobby, we now stroll through the southern half of the museum. The first room has sculptures of the archaic period (700–480 B.C.). The free-standing statues here are idealized representations of a young man, known in Greek as a kouros, or a young woman, or kore, which were placed as dedicatory offerings in temples of Apollo and Artemis. The most notable are a legless kouros and a kouros from Samos, the face in both cases showing the haunting archaic style characteristic of Greek sculpture of this period. The finest relief is from Cyzicus, showing a long-haired youth driving a chariot drawn by two horses.