Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (75 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

All the Byzantine churches in Istanbul are built of brick, including Haghia Sophia, and they were generally little adorned on the exterior, depending for their effect on the warm brick colours of the walls and the darker areas of windows which were usually plentiful and large. Towards the end of the Empire in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, exteriors were sometimes enlivened by polychrome decoration in brick and stone, seen at its best and most elaborate in the façade of the outer narthex of St. Theodore (Kilise Camii) or in that of the palace of Constantine Porphyrogenitus (Tekfur Saray). As if to compensate for the relative austerity of the outside, the interior of the churches blazed with colour and life. The lower parts of the walls up to the springing of the vaults were sheathed in marble, while the vaults, domes and upper walls were covered in gold mosaic. The most magnificent example of marble revetment is that in Haghia Sophia where a dozen different kinds of rare and costly marbles are used, the thin slabs being sawn in two and opened out so as to form intricate designs. The Great Church was of course unique, though there may have been a few others of Justinian’s time almost equally lavishly covered with marble. But even the humbler and smaller churches of a later period had their revetment, largely of the common but attractive greyish-white Proconnesian marble quarried from the nearby Marmara Island. Most of the churches have now lost this decoration, but an excellent example survives almost intact at St. Saviour in Chora (Kariye Camii).

The mosaics of the earlier period seem to have consisted chiefly of a gold ground round the edges of which, emphasizing the architectural forms, were wide bands of floral decoration in naturalistic design and colours; at appropriate places there would be a simple cross in outline. Quantities of this simple but effective decoration survive from Justinian’s time in the dome and the aisle vaults of Haghia Sophia. It appears that in Haghia Sophia at least there were originally no pictorial mosaics. In the century following Justinian’s death, however, picture mosaics became the vogue and an elaborate iconography was worked out which regulated what parts of the Holy Story should be represented and where the pictures should be placed in the church building. Then came the iconoclastic age (711 to 843) when all these pictural mosaics were ruthlessly destroyed, so that none survive in Istanbul before the mid-ninth century. From then onward there was a revival of the pictorial art, still in the highly stylized and formal tradition of the earlier period, and all the great churches were again filled with holy pictures. A good idea of the stylistic types in vogue from the ninth to the twelfth centuries can be seen in the examples that have been uncovered in Haghia Sophia.

But in Istanbul the most extensive and splendid mosaics date from the last great flowering of Byzantine culture before the fall. At the beginning of the fourteenth century were executed the long cycles of the life of the Blessed Virgin and of Christ in St. Saviour in Chora, which have been so brilliantly restored in recent years to their pristine splendour by the Byzantine Institute. To this date also belong the glorious frescoes in the side chapel of that church and another series of mosaics, less extensive but hardly less impressive in the side chapel of St. Mary Pammakaristos (Fethiye Camii). The art of these pictures shows a decisive break away from the hieratic formalism of the earlier tradition and breathes the very spirit of the Renaissance as it was beginning to appear at the same date in Italy. In Byzantium it had all too short a life.

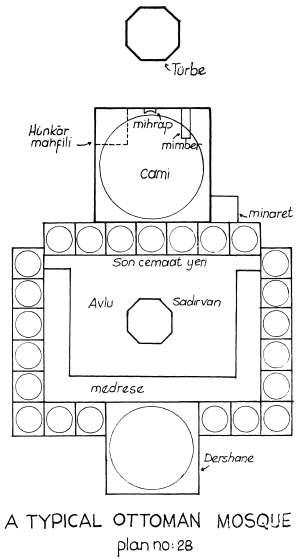

GLOSSARY OF TURKISH ARCHITECTURAL TERMS

avlu: courtyard of a mosque

cami: mosque; mescit, from which the European word mosque is derived, means a small mosque

dershane: the lecture hall of a medrese

dar-ül hadis: school for learning sacred tradition

dar-ül kura: school for learning the Kuran

dar-ü

ş

ş

ifa: hospital

hamam: Turkish bath

hücre: a cell of a medrese where a student lives

hünkâr mahfili: raised and screened box or loge for the sultan and his suite

imaret: public kitchen

kervansaray or han: inn or hostel for merchants and travellers

külliye: building complex forming a pious foundation (vak

ı

f) and often including mosque, türbe, medrese and other buildings

kürsü: preaching chair used on ordinary occasions

kütüphane: library

medrese: a school or college sometimes forming the court yard of a mosque

mektep or sibyan mektebi: primary school

mihrab: niche indicating the direction of Mecca (k

ı

ble) towards which all mosques are oriented; from Istanbul this is very nearly south-east

mimber: tall pulpit to right of mihrab used at the main Friday prayer

müezzin mahfili: raised platform for chanters

ş

ad

ı

rvan: fountain for ritual ablutions

son cemaat yen: porch of a mosque (lit. “place of last assembly”)

tabhane: hospice for travelling drevishes

tekke: convent for dervishes

türbe: tomb or mausoleum, often in a mosque garden

Note:

the forms

camii, medresesi, türbesi

and similar forms for other words are used when a noun is modified by a preceding noun; thus Sultan Ahmet Camii, but Yeni Cami, New Mosque.

The mosques of Istanbul fall into a small number of fairly distinctive types of increasing complexity. The simplest of all, used at all periods for the less costly buildings, is simply an oblong room covered by a tiled pitched roof; often there was an interior wooden dome, but most of these domes have perished in the frequent fires and been replaced by flat ceilings. Second comes the square room covered by a masonry dome resting directly on the walls. This was generally small and simple but could sometimes take on monumental proportions, as at Yavuz Selim Camii, and occasionally, as there, had side rooms used as hostels for travelling dervishes. At a later period in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries a more elaborate form of this type was adopted for the baroque mosques, usually with a small projecting apse for the mihrab.

The next two types both date from an earlier period and are rare in Istanbul. Third is the two-domed type, essentially a duplication of the second, forming a long room divided by an open arch, each unit being covered by a dome. It is derived from a style common in the Bursa period of Ottoman architecture and hence often known as the “Bursa type” (see the plan of Mahmut Pa

ş

a Camii). A modification occurs when the second unit has only a semidome. Mosques of this type always have side chambers. A fourth type, of which only two examples occur in Istanbul, also derives from the earlier Selçuk and Ottoman periods; a rectangular room covered by a multiplicity of domes of equal size supported on pillars; this is often called the great mosque or Ulu Cami type.

The mosques of the classical period – what most people think of as the “typical” Ottoman mosques – are rather more elaborate. They derive from a fusion of a native Turkish tradition with certain elements of the plan of Haghia Sophia. The great imperial mosques have a vast central dome supported on east and west by semidomes of equal diameter. This strongly resembles the plan of Haghia Sophia, but there are significant differences, dictated partly by the native tradition, partly by the requirements of Islamic ritual. In spite of its domes Haghia Sophia is essentially a basilica, clearly divided into a nave and side aisles by a curtain of columns both on ground floor and gallery level. The mosques suppress this division by getting rid of as many of the columns as possible, thus making the interior almost open and visible from all parts. Moreover the galleries, at Haghia Sophia as wide as the aisles, are here reduced to narrow balconies against the side walls. This is the plan of Beyazit Camii and the Süleymaniye. Sometimes this centralization and opening-up is carried even farther by adding two extra semidomes to north and south, as at the

Ş

ehzade, Sultan Ahmet and Yeni Cami. A further innovation of the mosques as compared with Haghia Sophia is the provision of a monumental exterior in attractive grey stone with a cascade of descending domes and semidomes balanced by the upward thrust of the two, four or six minarets.

Another type of classical mosque is also derived from a combination of a native with a Byzantine tradition. This consists of a polygon inscribed in a square or rectangular area covered by a dome. Its prototypes are the early Üç

Ş

erefeli Mosque at Edirne and SS. Sergius and Bacchus here; the former has an inscribed hexagon, the latter an octagon. In the classical mosques of this type (both hexagon and octagon being common) there are again no central columns or wide galleries, the dome supports being pushed back as near as possible to the walls, thus giving a wholly centralized effect. Though this was chiefly used by Sinan and other architects for mosques of grand vezirs and high officials, the most magnificent example of this type is the great mosque of Selim II at Edirne, Sinan’s masterpiece and the largest and most beautiful of all the classical mosques.

Almost all mosques of whatever type are preceded by a porch of three or five domed bays and generally also by a monumental courtyard with a domed arcade. If there is only one minaret – as in all but imperial mosques – it is practically always on the right-hand side of the entrance.

All imperial mosques and most of the grander ones of vezirs and great lords form the centre of a külliye, or complex of buildings, forming one vak

ı

f, or pious foundation, often endowed with great wealth. The founder generally built his türbe, or mausoleum, in the garden or graveyard behind the mosque; these are simple buildings, square or polygonal, covered by a dome and with a small entrance porch, sometimes beautifully decorated inside with tiles. Of the utilitarian buildings, almost always built round four sides of a central arcaded and domed courtyard, the commonest is the medrese, or college. The students’ cells, each with its dome and fireplace, opened off the courtyard with a fountain in the middle, and in the centre of one side is the large domed dershane, or lecture hall. Sometimes the medrese formed three sides of a mosque courtyard, and very occasionally they take unusual shapes like the octagonal one of Rüstem Pa

ş

a. These colleges were of different levels, some being mere secondary schools, others of a higher status, and still others for specialized studies such as law, medicine and the hadis, or traditions, of the Prophet.

Primary schools too (sibyan mektebi) were generally included in a külliye, a small building with a single domed classroom often built over a gateway and sometimes including an apartment for the teacher. Tekkes, or convents for dervishes, do not usually differ much in structure from medreses, but the dershane room, which may be in the centre of the courtyard, is used in tekkes for dervish rituals.

The larger imperial foundations included a public kitchen and a hospital. Like medreses these were built round a central courtyard, and the hospitals (dar-ü

ş

ş

ifa or timarhane) are almost indistinguishable from them, also having cells for the patients and a large central room like a dershane used as a clinic and examining office. The public kitchens (imaret) instead of cells have vast domed kitchens with very characteristic chimneys, and also large refectories. They provided food for the students and teachers of the medrese, the clergy of the mosque, and the staff and patients of the hospital, as well as for the poor of the neighbourhood. One or two of them still perform the latter service. All these institutions were entirely free of charge and in the great period very efficiently managed.

Fountains are ubiquitous. They are of three kinds: the

ş

ad

ı

rvan is a large fountain in the middle of a mosque courtyard used for ritual ablutions; the sebil, often at the corner of the outer wall of a mosque precinct, is a monumental domed building with three or more grilled openings in the façade through which cups of water were handed by an attendant to those who asked; the çe

ş

me is also sometimes monumental, often in the middle of a public square, but more frequently it is a simple carved marble slab with a spigot in the centre and a basin below: up until recent years scores of these were still in use to provide much of the population of the city with all the water they received.

Of the secular buildings the most important are the inn or hostel, the Turkish bath and the library. The hostel was usually called han if in a city, kervansaray if on the great trade routes; while tabhane was a hostel originally designed for travelling dervishes. Like so many other buildings it was built round one or more courtyards but was in two or three storeys, the lower one being used for animals and the storage of merchandise (since most travellers were merchants journeying in caravans), the upper ones as guest rooms (see the plan of Valide Han

ı

). The bath or hamam, a rather elaborate building, is fully described, including a plan, in connection with the Ca

ğ

alo

ğ

lu Hamam

ı

. The library (kütüphane) was often a simple domed room with bookcases in the centre; like the mektep it was sometimes built above the monumental gateway of a mosque enclosure, but it was sometimes independent and more elaborate (see the description of the Atif Efendi library).