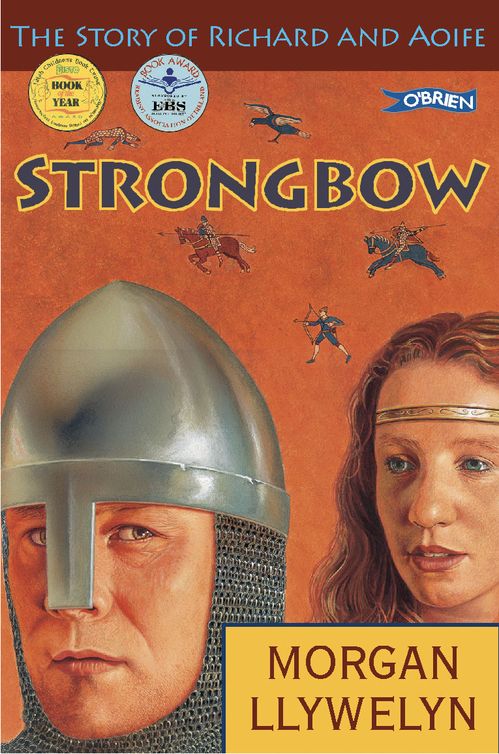

Strongbow

Authors: Morgan Llywelyn

DOUBLE AWARD-WINNER

Bisto Book of the Year

Reading Association of Ireland Award

‘The reader is spellbound’

THE IRISH TIMES

Norman knight and adventurer, Strongbow, has been part of Irish historical lore for centuries. But how many know the real story of his life?

Aoife is the daughter of a king who is despised by many of his peers – how will her life change after marrying Strongbow?

The Story of

R

ICHARD AND

A

OIFE

MORGAN LLYWELYN

For Slaney and Lucia O’Brien

John Bowden

James Langan

The story is told by the two main characters – Aoife, daughter of Dermot Mac Murrough, and Richard de Clare, who was called Strongbow. They give their account every second chapter.

2 Richard

Preparing for a Hard Life

3 Aoife

An Insult to the King of Brefni

4 Richard

Kings Have Ways of Getting Even

8 Richard

A Visitor from Ireland

12 Richard

Gathering Fighting Men

14 Richard

Facing King Henry II

16 Richard

I’ve Come to Be a King

17 Aoife

Meeting a Future Husband

18 Richard

A Strange Irish Custom

19 Aoife

The Marriage of Aoife and Strongbow

22

Richard

A New King in Leinster

When I was a little girl I didn’t know my father was a monster. He wasn’t a monster in those days, he was simply Father, a dark man with a curly beard. His beard tickled my neck when he nuzzled me, pretending to be a bear. In his growly bear-voice he’d say, ‘I’m going to eat you up, Aoife. First your shoulder, then your arm, then every tender little finger. Grrr!’

This was an old game with us. ‘Help, help!’ I’d cry. ‘Will anyone save me from this savage bear?’

Then Father would change from his bear-voice to his Father-voice that always made me feel safe and warm. ‘I’ll save you, Aoife,’ he’d promise. ‘No bear will eat you! No harm will come to you! Not while Dermot of Leinster lives.’ And he’d lift me high in his arms and swing me around and around, the two of us laughing and happy together.

That was Father.

Dermot Mac Murrough, King of Leinster, must have been a different man, though they lived in the same skin. When my father rode off to do king-things I thought he was making other people happy the way he made me happy. I didn’t know, in those days, that there were people who feared and hated him. I never imagined that in years to come his name would be used to frighten naughty children.

I never dreamt my father would someday be called a monster.

I didn’t understand what it meant to be a king. I thought other people lived as we did, in palaces of stone with solar rooms to let in the sun so the women could sew. I thought everyone had warm clothes dyed bright colours, and arm rings of silver and copper, and gold balls to fasten their hair. Just like us.

When Father had to be away, he always came back with gifts for his families. His first family was that of his senior wife, Mor, of the clan O’Toole. She and her children had the best chambers. Mor’s brother Laurence was an important priest, the Abbot of Glendalough, who would become Archbishop of Dublin one day. Father had held him hostage once, before any of us were born, and they had been friends ever since. That, I suppose, was why Father married his sister.

Father’s second family was that of Sive, of the clan O’Faolain, who was my mother. Kings needed to have a lot of children, so they could have more than one wife. Father even had a son called Donal whose mother wasn’t a wife of his at all. Donal Mac Murrough Kavanaugh didn’t live with us, but he often came to visit us at Ferns. He was Father’s oldest son, and beloved.

Father loved me most, though. Once he came back from Dublin with a Norse pony the colour of the sun, with a creamy mane and tail. It was so beautiful we all wanted it, but he gave it to me.

‘This is for my merry girl, my Aoife,’ Father said.

My big sister Urlacam – Urla for short – stuck out her tongue at me behind his back. But she wouldn’t have ridden the pony much anyway. She had grown lazy and stayed indoors most of the time, fussing with her clothes and her hair.

I was never lazy. I’m sure that Donal and my brothers Enna and Conor never had as many adventures as I did. I went everywhere on my pony. I was awake and out under the Leinster sky almost every morning before the sun was up. I loved to gallop across the damp meadows on a summer morning, feeling the wet grass brush my bare

legs. My pony loved it, too. He’d shake his thick mane and toss his head and I’d laugh out loud, I felt so good.

Once the pony threw me off and broke my arm. It hurt terribly, worse than a giant toothache. I didn’t want Father to see me cry, though, so I set my jaw and tried to smile. He smiled back at me.

‘My brave Aoife,’ he said.

A local bone-setter took care of servants and farmers when they broke bones, but because Father was a king he had his own physician. The man was an

ollav

, the best of his profession, and he was sent for.

The ollav tugged and pulled at my arm. White lights flashed in my eyes and my ears began to ring. Father had gone off somewhere by then. No one saw me cry but the ollav and my sister Urla, who was spying on me as always.

The ollav bound my arm to a board carved with healing symbols, then wrapped it in cloths covered with a thick paste of soot and egg white and pounded comfrey root. It smelled awful.

‘Your arm will heal in a moon’s time,’ the ollav promised, patting my cheek. His hands were very soft. ‘Do you know what your name means, Aoife?’ he asked.

Urla said quickly, ‘It means ugly because she has such big bones, like a horse, and such bright red hair.’

The ollav frowned at my sister. ‘You’re wrong,’ he told her. ‘Aoife means radiant, beautiful.’

Father’s physician had called me beautiful, and he should know. He was an educated man, not an ignorant bone-setter with rough hands! That was when I began to understand that being a king made Father special. Kings were surrounded by men like the ollav.

My arm healed. I forgot the pain. I rode my pony again and didn’t let it throw me off. Father gave me a glass ball the colour of rainbows as a reward. Then he gave me a little wooden box with two leaves hinged together, each holding a tablet of wax.

‘Under the law, a king’s daughter may be taught to read and write,’

he told me. ‘You’re to scribe your letters in this.’ He gave me a pointed stick called a stylus and showed me how.

You see? My father was not a monster. He had become King of Leinster when he was only sixteen years old, and everyone had envied him. He had been through some hard times. But he was respected at home in Ferns, and his families loved him.

As a child, I played all the time. I played ball and chase-me and all-fall-down with my brothers and my little sister Dervla. I played with the servants’ children too, and they taught me how to fish and to climb trees. My brother Enna, who was often sickly, taught me a song about a blue cow.

We ate our meals at tables of oak in the great hall. Some of the servants would smile at me when passing the food. I always smiled back. They were like part of the family, in a way. They were members of clans tributary to Father. Tributary means that their clans were not as important in Leinster as Father’s clan, and so had to pay tribute to him. Sometimes that meant sending him servants for his houses. He always took very good care of these people, just as he did of us.

The servants didn’t dress as well as we did, of course. To keep our feet warm in cold weather we wore

cuarans

of soft leather, with pointed toes. But servants went barefoot in all weathers.

So did I – when my mother wasn’t watching. I loved to run barefoot with my long hair blowing behind me. When Mother caught me she would cluck her tongue and shake her head, and fasten my hair into horrible thick plaits that hung down my back like ropes.

But I found a way to enjoy those plaits. I loved playing rough games with the boys, because I hated to sit in the solar, sewing, like Urla. Once when my brothers and the servants’ sons were playing a game of war, I picked up some long, narrow, sharp stones. I ran them through the plaits of my hair. When I spun around, the weighted plaits swung around me in a wide circle. No one dared come close to me, for fear of being hit in the face with them. A grand weapon!

My mother came outside and saw me, and shouted, ‘You could hurt someone, Aoife!’

‘I’m not trying to hurt anyone, we’re just having fun.’

Mother put her hands on her hips and scowled. ‘Really, Aoife, I don’t know what will become of you. Sometimes you’re like a wild creature.’

But when she told Father the story, he laughed.