Stuka Pilot (20 page)

Authors: Hans-Ulrich Rudel

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #World War II, #War & Military

After lying there for five minutes I am faintly recharged and summon up the strength to crawl up the sloping bank. But remorselessly the same mishap is repeated very soon, at latest at the next uneven ground. So it goes on till 9 p.m. Now I am done in. Even after longish rests I cannot recover my strength. Without water and food and a pause for sleep it is impossible to carry on. I decide to look for an isolated house.

I hear a dog barking in the distance and follow the sound. Presumably I am not too far from a village. So after a while I come to a lonely farmhouse and have considerable difficulty in evading the yelping dog. I do not like its barking at all as I am afraid it will alarm some picket in the near-by village. No one opens the door to my knocking; perhaps there is no one there. The same thing happens at a second farmhouse. I go on to a third. When again nobody answers impatience overcomes me and I break a window in order to climb in. At this moment an old woman carrying a smoky oil lamp opens the door. I am already half way through the window, but now I jump out again and put my foot in the door. The old woman tries to shove me out. I push resolutely past her. Turning round I point in the direction of the village and ask: “Bolshewisti?” She nods. Therefore I conclude that Ivan has occupied the village. The dim lamplight only vaguely illumines the room: a table, a bench, an ancient cupboard. In the comer a grey-headed man is snoring on a rather lopsided trestle bed. He must be seventy. The couple share this wooden couch. In silence I cross the room and lay myself down on it. What can I say? I know no Russian. Meanwhile they have probably seen that I mean no harm. Barefoot and in rags, the tatters of my shirt sticky with coagulated blood, I am more likely to be a hunted quarry than a burglar. So I lie there. The old woman has gone back to bed beside me. Above our heads the feeble glimmer of the lamp. It does not occur to me to ask them whether they have anything to dress my shoulder or my lacerated feet. All I want is rest.

Now again I am tortured by thirst and hunger. I sit up on the bed and put my palms together in a begging gesture to the woman, at the same time making a dumb show of drinking and eating. After a brief hesitation she brings me a jug of water and a chunk of corn bread, slightly mildewed. Nothing ever tasted so good in all my life. With every swallow and bite I feel my strength reviving, as if the will to live and initiative has been restored to me. At first I eat ravenously, then munching thoughtfully, I review my situation and evolve a plan for the next hours. I have finished the bread and water. I will rest till one o’clock. It is 9:20 p.m. Rest is essential. So I lie back again on the wooden boards between the old couple, half awake and half asleep. I wake up every quarter of an hour with the punctuality of a clock and check the time. In no event must I waste too much of the sheltering dark in sleep; I must put as many miles as possible behind me on my journey south. 9:45, 10 o’clock, 10:15, and so on; 12:45, 1:00 o’clock.—Getting up time! I steal out; the old woman shuts the door behind me.. I have already stumbled down a step. Is it the drunkenness of sleep, the pitch dark night or the wet step?

It is raining. I cannot see my hand before my face. My star has disappeared. Now how am I to find my bearings? Then I remember that I was previously running with the wind behind me. I must again keep it in my back to reach the South. Or has it veered? I am still among isolated farm buildings; here I am sheltered from the wind. As it blows from a constantly changing direction I am afraid of moving in a circle. Inky darkness, obstacles; I barge into something and hurt my shins again. There is a chorus of barking dogs, therefore still houses, the village. I can only pray I do not run into a Russian sentry the next minute. At last I am out in the open again where I can turn my back to the wind with certainty. I am also rid of the curs. I plod on as before, up hill, down dale, up, down, maize fields, stones, and woods where it is more difficult to keep direction because you can hardly feel the wind among the trees. On the horizon I see the incessant flash of guns and hear their steady rumble. They serve to guide me on my course. Shortly after 3 a.m. there is a grey light on my left—the day is breaking. A good check, for now I am sure that the wind has not veered and I have been moving south all right. I have now covered at least six miles. I guess I must have done ten or twelve yesterday, so that I should be sixteen or eighteen miles south of the Dniester.

In front of me rises a hill of about seven hundred feet. I climb it. Perhaps from the top I shall have a panorama and shall be able to make out some conspicuous points. It is now daylight, but I can discover no particular landmarks from the top; three tiny villages below me several miles away to my right and left. What interests me is to find that my hill is the beginning of a ridge running north to south, so I am keeping my direction. The slopes are smooth and bare of timber so that it is easy to keep a look out for any one coming up them. It must be possible to descry any movement from up here; pursuers would have to climb the hill and that would be a substantial handicap. Who at the moment suspects my presence here? My heart is light, because although it is day I feel confident I shall be able to push on south for a good few miles. I would like to put as many as possible behind me with the least delay.

I estimate the length of the ridge as about six miles; that is interminably long. But—is it really so long? After all, I encourage myself, you have run a six mile race—how often?—and with a time of forty minutes. What you were able to do then in forty minutes, you must now be able to do in sixty—for the prize is your liberty. So just imagine you are running a marathon race!

I must be a fit subject for a crazy artist as I plod on with my marathon stride along the crest of the ridge in rags—on bare, bleeding feet—my arm hugged stiffly to my side to ease the pain of my aching shoulder.

You must make it… keep your mind on the race… and run… and keep on running.

Every now and again I have to change to a jog-trot and drop into a walk for perhaps a hundred yards. Then I start running again… it should not take more than an hour…

Now unfortunately I have to leave the protective heights, for the way leads downhill. Ahead of me stretches a broad plain, a slight depression in exactly the same direction continues the line of the ridge. Dangerous because here I can be more suddenly surprised. Besides, the time is getting on for seven o’clock, and therefore unpleasant encounters are more likely.

Once again my battery is exhausted. I must drink… eat… rest. Up to now I have not seen a living soul. Take precautions? What can I do? I am unarmed; I am only thirsty and hungry. Prudence? Prudence is a virtue, but thirst and hunger are an elemental urge. Need makes one careless. Half left two farmhouses appear on the horizon out of the morning mist. I must effect an entry.

I stop for a moment at the door of a barn and poke my head round the corner to investigate; the building yawns in my face. Nothing but emptiness. The place is stripped bare, no harness, no farm implements, no living creature—stay!—a rat darts from one comer to another. A large heap of maize leaves lies rotting in the barnyard. I grub amongst them with greedy fingers. If only I could find a couple of corncobs… or only a few grains of corn… But I find nothing… I grub and grub and grub… not a thing!

Suddenly I am aware of a rustling noise behind me. Some figures are creeping stealthily past the door of another barn: Russians, or refugees as famished as I am and on the self—same quest? Or are they looters in search of further booty? I fare the same at the next farm. Here I go through the maize heaps with the greatest care—nothing. Disappointedly I reflect: if all the food is gone I must at least make up for it by resting. I scrape myself a hole in the pile of maize leaves and am just about to lie down in it when I hear a fresh noise: a farm wagon is rumbling past along a lane; on the box a man in a tall fur cap, beside him a girl. When there is a girl there can be nothing untoward, so I go up to them. From the black fur cap I guess the man is a Rumanian peasant.

I ask the girl: “Have you anything to eat?”

“If you care to eat this…” She pulls some stale cakes out of her bag. The peasant stops the horse. Not until then does it occur to me that I have put my question in German and have received a German answer.

“How do you come to know German?”

The girl tells me that she has come with the German soldiers from Dnjepropetrowsk and that she learnt it there. Now she wants to stay with the Rumanian peasant sitting beside her. They are fleeing from the Russians.

“But you are going straight in their direction.” I can see by their faces that they do not believe me. “Have the Russkis already reached the town over there?”

“No, that is Floresti.”

This unexpected reply is like a tonic. The town must lie on the Balti-Floresti railway line which I know. “Can you tell me, girl, if there are still any German soldiers there?”

“No, the Germans have left, but there may be Rumanian soldiers.”

“Thank you and God speed.”

I wave to the disappearing wagon. Now I can already hear myself being asked later why I did not “requisition” the wagon… the idea never entered my mind… For are the pair not fugitives like myself? And must I not offer thanks to God that I have so far escaped from danger?

After my excitement has died down a brief exhaustion overcomes me. For those last six miles I have been conscious of violent pain; all of a sudden the feeling returns to my lacerated feet, my shoulder hurts with every step I take. I meet a stream of refugees with handcarts and the bare necessities they have salvaged, all in panic-stricken haste.

On the outskirts of Floresti two soldiers are standing on the scarp of a sandpit; German uniforms? Another few yards and my hope is confirmed. An unforgettable sight!

I call up to them: “Come here!”

They call down: “What do you mean: come here! Who are you anyway, fellow?”

“I am Squadron Leader Rudel.”

“Nah! No squadron leader ever looked like you do.” I have no identification papers, but I have in my pocket the Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords. I pull it out of my pocket and show it to them. On seeing it the corporal says:

“Then we’ll take your word for it.”

“Is there a German Kommandantur?”

“No, only the rearguard H.Q. of a dressing station.”

That is where I will go. They fall in on either side of me and take me there. I am now crawling rather than walking. A doctor separates my shirt and trousers from my body with a pair of scissors, the rags are sticking to my skin; he paints the raw wounds of my feet with iodine and dresses my shoulder. During this treatment I devour the sausage of my life. I ask for a car to drive me at once to the airfield at Balti. There I hope to find an aircraft which will fly me straight to my squadron.

“What clothes do you intend to wear?” the doctor asks me. All my garments have been cut to ribbons. “We have none to lend you.” They wrap me naked in a blanket and off we go in an automobile to Balti. We drive up in front of the control hut on the airfield. But what is this? My squadron officer, Plt./Off. Ebersbach opens the door of the car:

“Pilot Officer Ebersbach, in command of the 3rd Squadron advance party moving to Jassy.”

A soldier follows him out carrying some clothes for me. This means that my naked trip from Floresti has already been reported to Balti from there by telephone, and Ebersbach happened to be in the control but when the message came through.

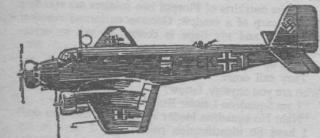

Ju. 52

He has been informed that his colleague who has been given up for dead will shortly arrive in his birthday suit. I climb into a Ju. 52, and fly to Rauchowka to rejoin the squadron. Here the telephone has been buzzing, the news has spread like wild fire, and the wing cook, Runkel, has already a cake in the oven. I look into grinning faces, the squadron is on parade. I feel reborn, as if a miracle had happened. Life has been restored to me, and this reunion with my comrades is the most glorious prize for the hardest race of my life.

We mourn the loss of Henschel, our best gunner with a credit of 1200 operational sorties. That evening we all sit together for a long while round the fire. There is a certain atmosphere of celebration. The Group has sent over a deputation, among them a doctor who is supposed to. “sit by my bedside.” He conveys to me the General’s congratulations with an order that I am to be grounded and to be flown home on leave as soon as I am in a fit condition to travel. Once more I shall have to disappoint the poor general. For I am deeply worried in my mind. Shall we be able to hold the Soviets now advancing southward in force from the Dniester? I could not lie in bed for a single day.

We are due to move to Jassy with all personnel the next morning. The weather is foul, impossible to fly. If we all have to be idle perforce I may as well obey the doctor’s orders and rest. The day after I fly with my squadron to Jassy, from where we have not so far to fly on our coming sorties over the Dniester. My shoulder is bandaged and I cannot move my arm, but that does not matter much when flying. It is worse that I have hardly any flesh on my feet and so naturally cannot walk. Every pressure on the controls involves acute pain. I have to be carried to my aircraft.