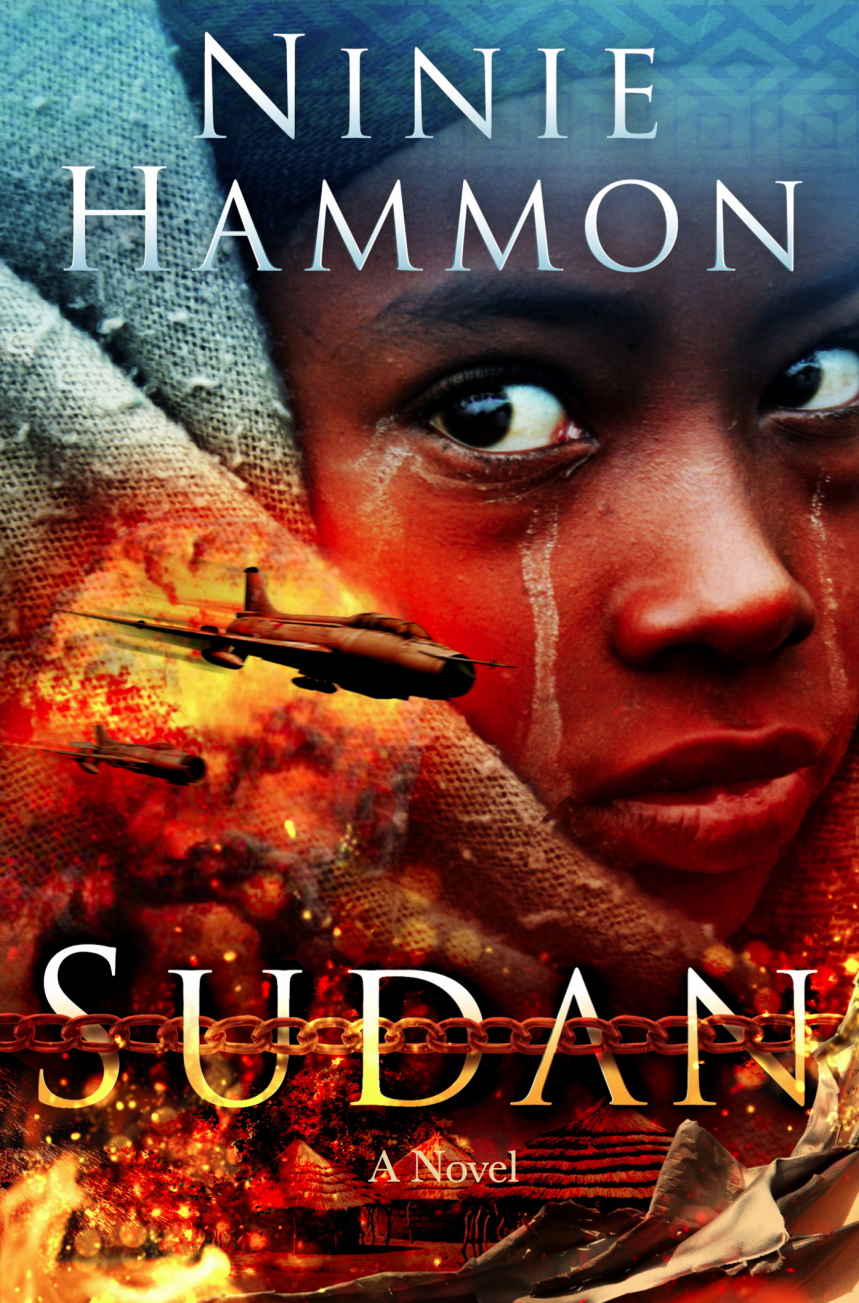

Sudan: A Novel

Authors: Ninie Hammon

By

N

INIE

H

AMMON

T

he sound of running feet dashing past her tukul was the first sign that something was not right in Dada Manut’s world. She’d been tickling baby Reisha’s tummy, sending the little girl into gales of giggles, but now she stopped and listened. She heard shouts in her sharply punctuated Lokuta dialect and then another sound, a sound she had never heard before, a high-pitched whine that couldn’t possibly have come from any animal or human she’d ever seen.

She snatched the naked baby into her arms and hurried outside. Her neighbors pointed at something in the eastern sky above the mountains. She squinted into the rising sun, but couldn’t make out the source of the strange noise that grew louder by the second.

She shifted Reisha to her hip, shielded her eyes with her left hand and peered into the glare. There! Now she could see it, see

them.

Two silver objects streaked across the sky toward her village, dropping lower and lower as they approached. The sound of them grew louder, rumbled like the thunder of a summer storm. Her heart began to hammer in her chest; her eyes widened in wonder—and growing dread.

Dada had never seen an airplane of any kind, much less a Soviet Antonov fighter. But she didn’t have to understand the incredible firepower bearing down on Nokot to sense the danger. Was this the death from the skies some of the other villagers talked about in hushed tones around their campfires at night, the tales of devastation too monstrous to comprehend? Information about the world outside their remote little valley was sketchy at best, but descriptions had filtered into Nokot of massive destruction and bloodshed--vague, shadowy stories as terrifying as bad dreams. Dada had dismissed the stories when she heard them, but now she began to back slowly toward the safety of her tukul, with its solid thatched roof and strong wooden support posts.

She didn’t make it inside before the first bomb fell.

The earth-shattering blast detonated less than 100 yards away, knocked her backward off her feet and slammed her to the ground so violently she almost lost her grip on Reisha. She lay there stunned, trying to catch her breath, her eardrums throbbing. In a daze, she turned in the direction of the blast, blinked her eyes and struggled to focus. But the world was not right. The stately balanite tree she and her friends had climbed when they were children was gone, replaced by a smoking crater of blackened earth with half a bloody zebu carcass draped over the edge. The rest of the animal was scattered in pieces around two other zebu that lay motionless nearby. Another blast hammered the earth on the other side of the village. Its roar mingled with the bleat of panicked goats as they stormed out of their pens, screaming caw-caws of terrified guinea hens and shrieks of women and children in a frantic stampede away from the carnage. Then she heard, as if from a great distance, the terrified screams of her infant daughter in her arms.

Dada staggered to her feet and lurched toward the doorway of her hut. Inside, both her sons sat on their sleeping mats, too frightened and bewildered to move. Dada knelt and pulled them close, held their trembling bodies tight, felt the staccato pounding of their little hearts against her chest.

Above the screams of the villagers and the cries of terrified livestock, she could hear the high-pitched whine of the fighter jets grow louder and louder. They were coming back. The strange otherworldly sound again became the rumbling of thunder, and Dada had time to wonder if she should run for cover in the woods or stay here where her husband and older son could find her. Then the bombs began to fall.

Four deafening explosions rocked the earth at two- to three-second intervals, cutting a swath of devastation 50 feet wide from one end of Nokot to the other. Huts that took direct hits vanished; others burst into flames. People and animals were indiscriminately blown apart, scattering body parts in a bloody hail in every direction.

Dada placed her shrieking baby on a sleeping mat but couldn’t get Isak and Kuak to sit down beside their sister; the boys were too terrified to let go of their mother. When she finally peeled them off and forced them to stay with Reisha, she stuck her head out past the elephant grass partition in the doorway. Her tukul was one of the few left standing. Four or five of her friends lay motionless on the ground nearby, and she could see the blood-soaked form of her seven-year-old nephew, Kagak, struggling to claw his way out of the remains of his family’s shattered, burning hut. But he could not crawl; both his legs had been blown off above the knee. His wailing mingled with the cries of the other injured villagers and animals in a symphony of terror and pain.

Dada’s eyes darted frantically from one horror to the next, taking it all in. Her heart boomed, and she could barely breathe through the rising knot of panic that gathered in her chest and flooded her mouth with a taste like blood. A purple light bloomed inside her head, and Dada felt hysteria crawling up the back of her throat, felt herself slipping, spiraling down toward the oblivion of total collapse. It was close, so achingly, temptingly close.

Everything in the world around her was wrong,

all wrong!

How could this be when the morning had started out like every other morning she had ever known? Dada’s mind suddenly reached out and grabbed hold of the morning, fiercely clutched the memory of normal and hunkered down into it. She left the acrid stench of burning bodies behind and snuggled up in a reality that was safe, a reality not defiled by exploding death, flames and blood.

She had awakened to the sound of the small herd of zebu lowing outside her tukul and had slowly raised herself on her elbow, careful not to disturb Reisha, curled up beside her breast. Two of her other children had been asleep on straw mats on the dirt floor of the one-room dwelling, but a third straw mat was empty. Her oldest son, Koto, was gone. He’d risen early to deliver the first of the zebu, large gray-and-white cattle with droopy ears, humps, and huge horns, to the pasturelands below their village.

Dada got up from the mat as quietly as she could and carefully nudged a tattered blanket closer to the baby to give her something to bump up against if she awoke. Then she edged past the sleeping forms of her two other children, and marveled again at how alike they were. There were times when even she would have struggled to tell them apart were it not for their lone distinguishing characteristic. Isak, the older of the eight-year-old twins by several minutes, had been born with a mark on the back of his right hand. To Dada, the mark was a shapeless blotch; to Isak, it was a butterfly! She paused briefly above each of the boys and gazed at them tenderly.

The face of the sun had just peeked over the Imatong Mountains on the border of Sudan and Kenya, and smiled down on the village where a half-dozen clans of migrating Lokuta tribals had settled 60 years earlier. Nokot now numbered 45 to 50 tukuls—round mud or straw huts with conical, thatched roofs.

Several women already squatted by their cast iron pots, stirring their family’s morning meal of porridge and cassavas. One of them was her sister, Bette, and she smiled a greeting. Koto was nowhere to be seen, so Dada walked over to their smoldering fire, picked up a stick and began to poke the embers, adding leaves and twigs, and blowing gently until flickering flames leapt from the red coals. Yesterday, she and Koto had gathered a large pile of acacia limbs, enough to fuel the family oven for several days. Like the rest of the families in their isolated village, they kept their fire stoked through the night and added dried zebu dung to produce a pungent smoke to hold at bay the seroot flies that carried the dreaded sleeping sickness. Everything in the village, every hut, mat, dried animal skin, thatched roof—and all the villagers, too—smelled like the smoke; the stink was woven into the fabric of their everyday lives.

Gauging from the position of the sun, she estimated that her husband, John, her father, brothers and the other Nokot men had been in the millet fields for at least half an hour, planting the seeds that would produce a crop of sorghum. John’s face formed in her mind, and she smiled. She was married to a good man, and not all the women in the village could say that. Some of the men were lazy, but John worked extra hard because his withered right hand made simple tasks more difficult. No one knew exactly what had happened to him. He’d been only two years old, too little to tell his mother what had bitten him. A spider, maybe. A millipede. A snake. The list of suspects was huge. His mother had washed the wound with river water and put a poultice of leaves and boiled acacia bark on it. The toddler had been very sick for days; his hand had swollen to three times its normal size. When he recovered, he could no longer move his wrist, fingers or thumb, and over time, the hand withered and hung useless.

When John’s father had come to her father to negotiate a marriage, her father had been reluctant to agree, even when John’s father offered nine zebu. He’d feared John couldn’t properly care for Dada and a family, but Dada had pleaded with her father to approve. For years she had hoped John would be selected as her husband. He had kind eyes, and she’d watched him with his younger brothers and sisters. She knew he would be a good father. And she’d been right. When Isak had been born with the butterfly mark in the same spot on his hand where John had been bitten, Dada was certain that the spirit of John’s dead mother had put it there to protect her grandson from the fate of his father.