Suddenly Overboard (14 page)

Read Suddenly Overboard Online

Authors: Tom Lochhaas

Shortly after they reached shore in the lifeboat, they learned the skipper had been pronounced dead at the hospital.

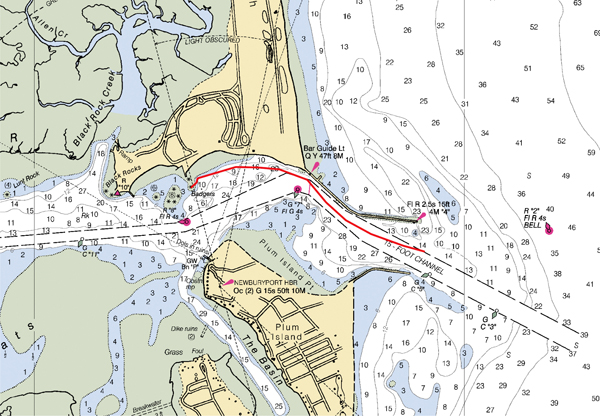

The mouth of the Merrimack River in northeast Massachusetts is one of the most dangerous boating areas on the East Coast. With a tidal flow that extends for several miles back from the Atlantic,

the Merrimack also brings water down from far up in New Hampshire, and its current is typically 3 knots or more on the flood tide and considerably faster after heavy rainfall upstream. Along the way the river picks up silt and sand and then funnels between two breakwaters extending a short distance into the ocean. Where the current slows as the river blends into the sea, sand is deposited on a bar that rises abruptly from a depth of 30 feet to only 8 to 9 feet at low tide. When the wind is east on a hard ebb tide, steep breakers form and make the river mouth impossible for small boats to navigate and dangerous for large ones.

Fortunately, a hard east wind is rare, although the water is often choppy on the tide. Added to this, especially on summer weekends, dozens of small fishing boats hover between the jetties or just outside and larger craft throw big wakes as they zoom in and out of the river. For the uninitiated the mouth can seem a hellish maw, and the locals know when to keep away. Reportedly, on average two boaters die there every year, typically fishermen on small skiffs overturned by a wave or a wake, and sometimes crew from a larger boat that broaches in the breakers and capsizes or is bashed against the granite blocks of the breakwaters. One year a powerboat captain lost his life after hitting the jetty.

On the flood tide the current reverses at the mouth, usually flattening the waves and easing speeding boats' return voyages to ports upriver. Then it's mostly a matter of paying attention to the markers, staying in the channel, and avoiding other boats. A few intrepid sailors even come in under sail, occasionally tangling with powerboaters who seem to understand neither the rules of right-of-way nor why a sailboat must sometimes tack diagonally across the channel. On busy weekends only the bravest sailors thread this gauntlet under sail.

Once between the jetties, headed in, the channel bears hard to starboard around a sandbar extending from Plum Island, on the port side, more than two-thirds of the way across the water. It's clearly marked on the chartâthe big green buoy with a flasher is obviousâand few boats risk cutting the corner below half tide. Yet

fishermen and beachgoers wading out on this sandbar sometimes get in trouble when the water rises fast behind them, and recently a young woman was washed off by the current and drowned.

Chart section showing the track of the sailboat into the rocks

.

This Saturday afternoon was a typical summer weekendâsunny, a light southwest breeze, the river full of boats. Joanna and Seth were happy to have their three children with them for the day's sail. One had driven up from Boston, and the other two were home for the summer from college. The family of five filled the cockpit of the 28-foot sloop to capacity, but they were a close family and having a great time. Joanna especially was pleased by how well the kids still got along, and for his part Seth was thrilled they still wanted to go sailing. So many friends complained that their children had lost interest.

Not only that, but they helped with the sailing, too. The oldest boy had taken the helm while Seth and the younger boy dropped and furled the main in preparation for motoring in.

The boys then decided to drop a fishing lure in the water and troll during the ride up the river. With so many fishing boats around they figured the stripers must be running. Seth took the helm and steered to skirt the shore to starboard and keep away from most of the fishing boats.

The flood tide was running hard, and though the knotmeter showed only 5 knots under diesel power, Seth knew they were probably doing at least 8 over the bottom. But to the powerboats zipping by to port, they must have looked like they were standing still.

Past the flasher at the inner end of the breakwater, he eased still more to starboard, watching sunbathers on the beach and listening to the chatter of the boys leaning over the stern rail with the fishing pole. There were no markers here, and deep water held almost up to the beach. A couple hundred yards along you had to turn almost 90 degrees to port, across the river, to leave the red flasher to starboard.

Just as he started the turn to port, the boys shouted that they had a fish. “Feels huge!” Immediately Seth throttled down to ease the strain on the line. He looked back and saw the pole's tip bent down toward the water.

He turned more to port to make for the red marker since the incoming tide swept you sideways at this point. Then he turned farther to port so the boat was facing directly across the river.

When they struck the rocks he was so surprised that at first he thought a boat had hit them on the starboard side, but there was nothing there. Alarmed, he turned hard to port and throttled up to head back toward the center of the channel. The keel hit again, harder, and the boat heeled suddenly hard to starboard as the current pushed against the port side. With a shudder, the engine died when the prop hit a jutting rock.

“Everyone hang on!” he shouted.

The boat stopped, heeled even more, and then with a grinding noise slid farther into the rocks 3 feet under the surface. It was now canted over more than 30 degrees.

When he was sure they had stopped, at least for the moment, Seth dashed below to check for leaks. Once in the cabin he heard the steady grinding of fiberglass against granite and could only hope it was the keel and not the hull.

The tide was rising fast and might float them off, but he realized that the current would just push them deeper into the rocks. Things would only get worse.

He rushed back up to the cockpit where everyone waited, Joanna white-faced. “I'm calling the harbor patrol,” he said. “We gotta get out of here.” He handed out PFDs from the cockpit locker.

Fortunately the local Coast Guard crew heard their radio call and responded within minutes in a rigid-hull inflatable rescue boat that could work in close enough to take them off. Later, back at the station after Seth had called a salvage company to try to retrieve their sailboat, one of the guardsmen took Seth aside. “I don't want to scare your family, but you're really lucky you didn't end up in the water. It's still damn cold, and you'd have been bashed around in that current or on the rocks where a boat couldn't get to you.” Seth nodded grimly. “And next time you might want to put your life jackets on before you need them. You never know.”

The Flinders Islet Race follows a 92ânautical mile course over mostly open ocean off New South Wales, Australia. While this race lacks the treacherous reputation of the SydneyâHobart race, it nonetheless commands the attention of participating sailors. The forecast for the race in October 2009 was nothing special. Earlier strong winds had abated, leaving a big swell, and race winds were forecast to be 20 to 25 knots and subsiding. Experienced racers

like Andrew Short weren't concerned about the weather but were looking forward to a fast, fun race.

Andrew had a crew of 17 aboard his 80-footer named

PriceWaterhouseCoopers

. He sailed often and knew the boat well. His friend Matt acted partly as tactician, and more than half of the others were regular crew on the boat. Some had sailed with him for over two decades on other boats. Others, like his friend Sally, were experienced sailors but new to this boat. All of them had gotten used to Andrew's style of sailing, however.

He liked to be in control, even though he was more relaxed than dictatorial in his command. He generally kept the helm for himself and also made the navigational and most tactical decisions. Unlike most other skippers he didn't plan out a rotation of crew roles in advance. After all, he likely reasoned before the race, it's only 92 miles, not a multiday race where you need to set watch schedules for sleeping.

So he took the helm as usual well before the start, late Friday, after a day's work. The adrenaline was flowing, and the crew was as happy as they could be in this weather. Everyone had full confidence in him as the skipper. They made a good run on the starting line and headed off downwind for Flinders under spinnaker. The southwest breeze was moderate at the start, but they had a reef in the main because they anticipated more wind offshore.

The evening weather became unpleasantly cold after passing showers. The wind averaged about 20 knots but gusted near 30, with frequent shifts in direction. Waves a meter high built on top of the swell from yesterday's gale. Some of the crew were feeling queasy by midnight.

A little before 2

A.M

. they tacked onto port when the chartplotter showed they were about 6 miles from Flinders Islet. The plotter had been acting up earlier, but after they rebooted the system things seemed okay, and Andrew felt he could trust it now. The wind was still shifting, but he anticipated no problems in leaving Flinders to port, as required in the race, without having to tack again. He had been on the helm for about 7 hours now and was a

little tired, but the weather was clearing and they were cheered by the prospect of a more pleasant return sail back to Sydney.

The moon came out as they approached the islet from the southeast, steering approximately for its northern end some 3 miles off. Andrew had overstood the mark with the earlier tack in case of a wind shift but could now fall off some to starboard. The boat was humming along at 12 to 15 knots as the crew readied the spinnaker lines for a quick hoist after they rounded the islet. The spinnaker bag was positioned on the port railâthe high, windward sideâin preparation. The bag obscured Andrew's view forward from the cockpit on that side, but he was using the chartplotter more than line of sight as he steered to the mark.

PriceWaterhouseCoopers

, like many large race boats, had two wheels, and Andrew was mostly using the high, port wheel. The plotter was closer to the starboard wheel, however, so he kept moving back and forth, sometimes switching to the starboard wheel to check the view to leeward, although the headsail blocked most of the view forward from that position.

Matt was just forward of the mast, readying the spinnaker pole and control lines.

Andrew drove on, closing the mark, unwilling to lose ground by bearing off any more than necessary. He shouted commands to the trimmers but had not asked or assigned anyone to be forward lookout. His crew was used to that; Andrew never lacked confidence in his helming or tactical decisions.

The sky was clear as they approached the last mile. Flinders Islet was now an obvious silhouette against the shore lights of Port Kembla in the distance. Everyone was in position for the rounding.

The boat flew off a swell and was surfing fast when Matt suddenly heard breakers. He spun around and saw they were sailing straight at the waves breaking on the rocks of the islet's north end. “Come away!” he shoutedâand kept shoutingâand Andrew turned to starboard.

Matt was still shouting. Andrew turned more.

Then they struck.

The crew described it later like a car crash, an instant full stop that threw them forward on deck, gear flying everywhere. Matt had been tethered to a jackstay and was thrown from the mast to the forestay, where his tether held him.

A quick check showed that everyone was still aboard with nothing more than minor injuries. Miraculously the boat remained upright on the reef about 10 meters from the exposed rocks of the shore. Quickly they released the sheets to spill wind from the sails, hoping to steady the boat.

But breaking waves continued to slam the boat forward and it slid around to point straight at the islet, pitching fore and aft with the waves.

Almost immediately after striking Andrew had ordered the engine started with the hope of backing off the reef. It ran for 30 seconds, died, and would not restart.

Still at the port wheel, Andrew then directed someone to make a Mayday call, but abruptly the boat lost all electrical power. Crew reported the cabin was a mess down below, with gear and sails tossed everywhere in the dark and breaking waves flooding in.