Summer of '68: The Season That Changed Baseball--And America--Forever (17 page)

Read Summer of '68: The Season That Changed Baseball--And America--Forever Online

Authors: Tim Wendel

Tags: #History, #20th Century, #Sports & Recreation, #United States, #Sociology of Sports, #Baseball

From eight stories above the fray, Dierker and his roommate, Jim Ray, witnessed the police and National Guardsmen wade into the crowd. Their wrath on that night knew no bounds. As Kurlansky notes, the authorities beat “children and elderly people and those who watched behind police lines.... They dragged women through the streets. A crowd was pressed so hard against the windows of a hotel restaurant—middle-aged women and children, according to

The New York Times

—that the windows caved in and the crowd escaped inside. The police pursued them through the windows, clubbing anyone they could find, even in the hotel lobby.”

Although the police seemingly went out of their way to smash cameras, perhaps to keep images off the network feed, additional television cameras had been mounted above the hotel entrance, offering roughly the same angle Dierker and his teammates had. The mayhem went on for seventeen minutes—a bloodbath that can now be viewed on YouTube. Many who witnessed it firsthand were changed forever.

“Jim and I were just amazed by what was going on down below,” Dierker said. “I was in the same age group as the people who were upset about the war. Certainly protesting not only what was going on in Vietnam and Chicago, but what was going on in a cultural way with the music and fashion.

“I knew I was a part of that generation that was boiling up down below. At the time, I was more selfishly concerned with my own life and career. I didn’t feel a great kinship with the ones protesting. But once you see something like that, you don’t forget it so easily. Looking back on it, that night changed me . . .

“I wasn’t worried that they would call up my Guard unit and send me to Vietnam. I was somewhat insulated from the potential dangers that a lot of guys my age felt that they were in. I don’t consider myself unpatriotic, but if I had a chance to say whether I’d like to go to Vietnam and fight for my country or I’d like to stay home and have someone else do it, my choice was not to go, to play major league ball, and let someone else do it. That night I wasn’t proud of that.”

The Tigers’ Dick McAuliffe averaged .247 during his sixteen-year career. He never hit above .274 in a season and his high-water marks in home runs and runs batted in were twenty-four and sixty-six respectively, both in the 1964 season. To the average fan, he wasn’t anything special, just a guy who could play second base and shortstop. But his teammates knew better.

Today they still use words like aggressive, determined, and fiery to describe a player they nicknamed “Mad Dog.” Several remember a four-hit game when he singled each time and ended up on second due to his daring-do on the base paths. “He was the guy who made us go in ’68,” Gates Brown said. “Dick McAuliffe was the kind of player you could always count on and you know will cover your back. It’s hard to picture that’68 team without him.”

In late August, as things were about to erupt in Chicago, the Tigers and their fans were about to be reminded how valuable McAuliffe was. Born into an Irish-Italian family in Hartford, McAuliffe learned early on never to back down from anybody. In high school, he had batted against the legendary fireballer Steve Dalkowski. When he and McAuliffe confronted each other, Dalkowski was as fast and wild as ever. His fastball hit McAuliffe square in the back.

“That was as hard as I’ve ever been hit by a ball,” McAuliffe said. “I didn’t think I was going to breathe again.”

Despite being hunched over at the waist, McAuliffe made his way to first base that day. His teammates decided he must have really been hurting because he wasn’t able to shout out anything in Dalkowski’s direction.

That wasn’t the case on August 22, 1968. The White Sox were in town to play the Tigers, and there was no love lost between the two ballclubs. Over the past two seasons, former White Sox manager Eddie Stanky (who had been fired in July after a disappointing first half) had questioned Detroit’s makeup. He agreed that the Tigers certainly had the talent, but wondered aloud if they have the fortitude to win it all? McAuliffe was among those who remembered such slights.

Early on the storyline that day appeared to be Mickey Lolich’s return to the rotation. After weeks in bullpen purgatory, winning four games in the process, the enigmatic left-hander was back in the rotation and pitching well. He had made a half-dozen appearances out of the bullpen and recalled struggling not only with his control but also in regaining the quality sinking action on his pitches. “They just sat there,” Lolich said, “and people hit them. Simple as that.” Certainly McAuliffe was doing his best to make him a winner in his return. With his distinctive batting style—bat held high, kicking his front leg toward the mound as the pitch arrived—McAuliffe led off the first inning with a single and scored the Tigers’ first run of the game.

In the third inning, McAuliffe was back at the plate, again facing White Sox starter Tommy John. The second pitch was a little chin music and McAuliffe turned to talk with home plate umpire Al Salerno. “If he hits me in the head, I’m dead,” McAuliffe said.

When the count ran to three and two, John came inside again, spilling McAuliffe face-first to the ground. As he started toward first base, he and John began to jaw at each other. About thirty feet up the line, McAuliffe suddenly made a beeline for the mound, where John waited for him. As McAuliffe charged, John dropped down, ready to throw a shoulder block. The two of them cracked together, with McAuliffe sprawling over the top. John’s left shoulder, his pitching arm, took the major force of the impact.

As far as baseball fights go, this one was over quickly. Nothing compared to the Cardinals-Reds brawl. In fact, McLain missed the whole thing because he was back in the clubhouse eating a hot dog. McAuliffe was ejected by Salerno and order was soon restored. That’s when everybody noticed John holding his left arm. Afterward, it would be determined that he had suffered torn ligaments in his pitching shoulder.

The Tigers went on to record a 4–2 victory. In his return to the rotation, Lolich was the winner, even though he failed to finish the game after beating out an infield single and later coming around to score. “He ran out of gas,” manager Mayo Smith told Jerry Green. “He didn’t even have a tiger in his tank.”

After the game, umpire Salerno said that he was required to send a report to American League president Joe Cronin about the McAuliffe-John altercation. In it he would say that McAuliffe was the aggressor. “I doubt he’ll be suspended, though,” Salerno said. “I don’t think John was throwing at him on a three-two pitch. But John did cuss him.”

With that the incident appeared to be over. But the following day, with the Tigers in New York to play the Yankees, word came down that McAuliffe was suspended for five days. With a doubleheader thrown in, he would miss the next six of Detroit’s games.

At the time, the Tigers held a relatively comfortable seven-and-a-half-game lead over second-place Baltimore, but they were about to find out the difference one player can make. McAuliffe’s suspension exposed a key weakness with the Tigers’ roster.

In the first game without McAuliffe, Detroit lost 2–1 to the Yankees. The second game of the doubleheader went into extra innings, tied at 3–3. Just past one in the morning, it was called due to curfew—slated to be made up as a brand-new ballgame.

The next day not even McLain could stop the bleeding. He lost to the Yankees 2–1 on Roy White’s two-run homer. It was the first time all season McLain had lost two games in a row. From there things continued to snowball downhill for Detroit. At first, it looked as though the Tigers would take the first game of Sunday’s doubleheader easily, staking themselves to a 5–1 lead. But when Yankees manager Ralph Houk brought in outfielder Rocky Colavito to pitch in order to avoid depleting his bullpen in a losing effort, incredibly “The Rock” shut down the Detroit bats and the Yankees rallied for a 6–5 victory, with Colavito the game’s winner.

The victory couldn’t have been sweeter for The Rock. He had previously played for the Tigers, an integral member of the 1961 ballclub that had given the New York Yankees a run for their money. But Colavito never felt at home in the Motor City and often seemed to resent the adoration that Al Kaline in particular received. Colavito was no stranger to the mound, having pitched for the Indians in 1958, and he loved to mess around with throwing changeups and curveballs during warm-ups. “I feel so funky,” he said after his victory.

In comparison, the Tigers weren’t feeling very funky at all, especially after Lolich walked seven batters and the Yankees completed the four-game sweep, winning 5–4 in the day’s second game. With the losses, Detroit’s lead had been shaved to five games over Baltimore, with the Orioles coming to Detroit the following week for a three-game showdown. In the cramped visitors’ clubhouse at Yankee Stadium stood a blackboard. On it, someone had written, ANYBODY WHO THINKS THE WORLD ENDED TODAY DOESN’T BELONG HERE.

To this day, nobody is sure who the author was. Catcher Bill Freehan often receives credit, while others insist it had to be Eddie Mathews. Whoever the author was the Tigers were about to be tested after coasting for so long.

On September 4, 1968, bothered by a sore arm, Luis Tiant took the mound in Anaheim. Even though he lasted only five and two-thirds innings, allowing four earned runs, the Indians hitters did the job this time around and he was credited with the win. Five days later, on the road against the Twins, Tiant went the distance, giving up only one run, and at last secured his twentieth victory. But while he led the American League and ERA, the season had taken its toll and the damage was done. His next start was at home, against Baltimore. Before the contest, his arm throbbed so badly that second-year pitcher Steve Bailey was called on to take his place. After the Orioles beat the last-minute substitute, Alvin Dark questioned his top pitcher in the press. The next morning’s paper quoted Dark as being “surprised” that Tiant had quit. The quote prompted a confrontation later recounted in Tiant’s autobiography.

Storming into Dark’s office, Tiant flung the morning paper across the desk, hitting the manager in the chest.

“I never come in here with excuses,” Tiant said. “You should know that better than I do. The rest of these guys are always getting dizzy or having colds or not feeling good, but you never say anything in the papers about them. Why did you have to say this about me?”

“You’re taking it the wrong way,” Dark replied.

“I don’t care how I’m taking it,” Tiant answered. “ You’re not supposed to say those things about your players in the papers. I do my job for you and for this ballclub, so I should be respected. You never hear any excuses from me, but I’ve been pitching with a sore elbow and you know it.”

Dark tried to get a word in edgewise, but Tiant cut him off.

“From now on, if I don’t feel good, I don’t pitch,” the staff ace said. “I don’t care if you get mad, or if you trade me, or whatever else happens. If I’m not one hundred percent, I don’t pitch.”

Moments later, Tiant walked out of his manager’s office. Many of his teammates thought his impressive 1968 campaign was history.

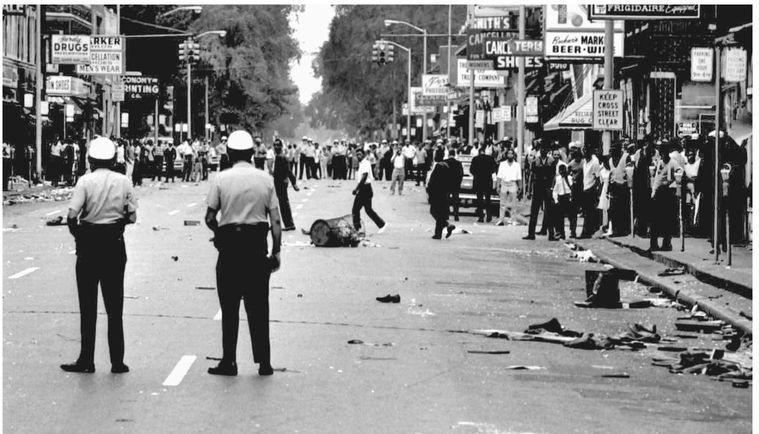

The city of Detroit burned during the summer of 1967 in one of the deadliest riots in U.S. history. As the new baseball season began, many in the city and on the hometown team feared such protests would break out again.

The Detroit News Archives

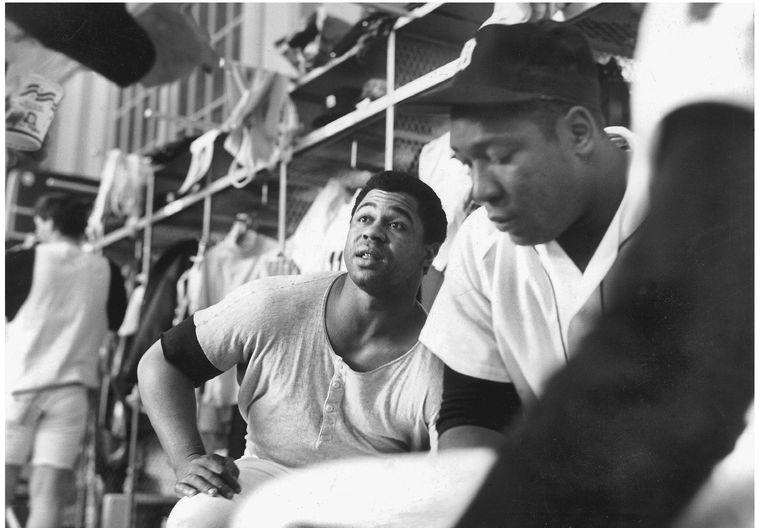

Willie Horton, left, shown here in the Tigers’ clubhouse with his good friend and Tigers teammate Gates Brown, risked his life trying to stop the ’67 riots. Many on the ballclub lived year-round in the Detroit area. They knew how far a winning ballclub could go in healing a divided city.

The Detroit News Archives

Just after 6 p.m. on April 4, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was shot in Memphis, Tennessee. He was standing on the balcony outside his room at the Lorraine Hotel, about to leave for dinner at his friend Billy Kyles’ house. Afterward, members of his party pointed in the direction where the shots were fired.