Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism (52 page)

Read Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism Online

Authors: James W. Loewen

Imagine going through elementary school without a single conversation with a fellow student! Still, the greater sorrow today may be Leslie’s.

97

97

Often teachers have encouraged students to isolate the one or two black children who ventured into a sundown town or suburb. Once in a while, this backfired. A Pinckneyville, Illinois, resident told how a high school gym teacher in the 1980s tried to get his students to shun Quincy, the one black child in the school:

He asked his class, “Are any of you friends with Quincy?” My son said, “I am.” “Take a lap.” Then he asked again. My son’s friend said, “I am.” “Take

two

laps.” Eventually every boy in the class volunteered.

She was going to complain to the principal, “but my son asked me not to: ‘Mom, we won.’ ” More often, whites maintained a united front, and the “intruders” left. In the early 1990s, for instance, an African American family tried to move into Berwyn, a sundown suburb just west of Chicago. The

Wall Street Journal

wrote a piece about how Berwyn had changed and how, despite minor aggravations, the family would stay. A week later the family left, James Rosenbaum at nearby Northwestern University wrote, because “they couldn’t stand the harassment, especially against the kids.” A resident of Ozark, Arkansas, recalled, “We used to have some blacks here, and we got rid of them.” As a junior high school student in 1995, she saw two African American children get beaten up by white students as they got off their school bus on the first day of school in the fall. “They didn’t even get to school.” The family soon moved. A former police officer in Winston County, Alabama, much of which may yet be a sundown county, told me, “In 1996 [whites] held a meeting to try to kick the one black child out of the school in Addison.” He believed that the child stayed in school, but imagine the social conditions under which s/he attended.

98

How One Town Stayed White Down the YearsWall Street Journal

wrote a piece about how Berwyn had changed and how, despite minor aggravations, the family would stay. A week later the family left, James Rosenbaum at nearby Northwestern University wrote, because “they couldn’t stand the harassment, especially against the kids.” A resident of Ozark, Arkansas, recalled, “We used to have some blacks here, and we got rid of them.” As a junior high school student in 1995, she saw two African American children get beaten up by white students as they got off their school bus on the first day of school in the fall. “They didn’t even get to school.” The family soon moved. A former police officer in Winston County, Alabama, much of which may yet be a sundown county, told me, “In 1996 [whites] held a meeting to try to kick the one black child out of the school in Addison.” He believed that the child stayed in school, but imagine the social conditions under which s/he attended.

98

Wyandotte, Michigan, illustrates the intimidation, violence, and even murder that towns and suburbs have used to enforce their sundown policy. Indeed, because Wyandotte began as an independent town but then became a suburb of Detroit, it shows how the same methods were used in both environments. Its public library has preserved a file of newspaper clippings, letters, and other material collected by Edwina DeWindt in 1945

99

that reveal the history of race relations in that city.

99

that reveal the history of race relations in that city.

Ironically, Wyandotte’s first non-Indian settler may have been John Stewart, “a free man of color and a Methodist” missionary to the Indians, who arrived at Wyandotte, an Indian village, in 1816. Despite this multiracial start, the last Wyandotte Indians were pushed out of Michigan in 1843, and Wyandotte also excluded African Americans some time before the Civil War, much earlier than most sundown towns. According to an October 1898 story in the

Wyandotte Herald,

“So far as

The Herald

remembers, [Wyandotte] has never had any permanent colored population.”

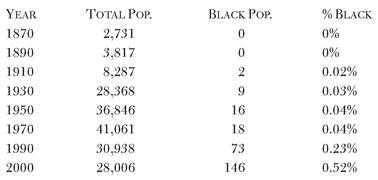

Table 2

shows Wyandotte’s population by race, from the U.S. census. Its numbers look like those from many other towns and suburbs: as Wyandotte grew from 2,731 in 1870 to 41,061 a century later, its African American population stayed minuscule, 0 in 1870 and 18, or 0.04%, in 1970. Along the years, the numbers fluctuated slightly, asas the table shows.

100

Wyandotte Herald,

“So far as

The Herald

remembers, [Wyandotte] has never had any permanent colored population.”

Table 2

shows Wyandotte’s population by race, from the U.S. census. Its numbers look like those from many other towns and suburbs: as Wyandotte grew from 2,731 in 1870 to 41,061 a century later, its African American population stayed minuscule, 0 in 1870 and 18, or 0.04%, in 1970. Along the years, the numbers fluctuated slightly, asas the table shows.

100

Table 2

. Population by Race, Wyandotte, Michigan, 1870–2000

. Population by Race, Wyandotte, Michigan, 1870–2000

“Wyandotte History; Negro” allows us to see the drama beneath those numbers. To maintain such racial “purity,” Wyandotte has long resorted to violence and the threat of violence. In 1868, “a colored wood chopper” moved into town:

He was a quiet, peaceable fellow who on his trips downtown had been reviled by rude boys.... One day a boy was foolish enough to strike him, upon which the worm turned and gave his assaulter a trouncing. The old spirit was aroused again; threats were made that the old darky should be driven out of town, and steps were taken to organize for that purpose, but . . . the authorities took a firm stand.... Twenty special constables were sworn in . . . and the trouble was over.

This 1868 response by “the authorities” was much better than African Americans would get in Wyandotte later in the century. Nevertheless, by 1870, the woodcutter was gone and Wyandotte had returned to a black population of zero.

101

101

In the early 1870s, “a colored barber opened a tonsorial parlor in the block between Kim and Oak streets.” A mob riddled the barbershop with bullets and ran the barber out of town. Shortly thereafter, a white mob stormed a little steamer that had landed in Wyandotte with a black deckhand on board and beat him nearly unconscious. In 1881 and again in 1888, whites threatened and expelled black hotel workers from Wyandotte, and in 1890, Wyandotte again had no African Americans among its 3,817 residents. In 1907, four young white men accosted African American William Anderson at the West Wyandotte train station. They “asked him if he was going to work in the shipyard, and although he gave a negative answer,” they gave him “a severe beating” and robbed him of $9.25. The authorities did nothing in response to any of these incidents.

102

102

Often Wyandotte whites had only to threaten violence. In the words of the Wyandotte file, “the policy popularly pursued to enforce the ‘tacit legislation’ (no Negroes in Wyandotte) is to approach the ‘stray’ Negro and abruptly warn him that a welcome mat is not at the gates of the city. This quiet reminder hastens the Negro’s footsteps with no further action.” But by 1916, mere threats must not have worked, because a few African Americans again lived in Wyandotte. In late August of that year occurred the worst riot in Wyandotte’s history. According to a story subheaded “Race Riot Monday Night” in the

Herald,

whites bombarded a black boardinghouse, smashed its doors and windows, drove out all African Americans, and killed one. “Colored People Driven from Town,” announced the

Herald.

“Most of the Negroes left town Monday night or Tuesday morning.”

103

Herald,

whites bombarded a black boardinghouse, smashed its doors and windows, drove out all African Americans, and killed one. “Colored People Driven from Town,” announced the

Herald.

“Most of the Negroes left town Monday night or Tuesday morning.”

103

A year later, a few African Americans were back in Wyandotte, working at Detroit Brass. This led to another expulsion. DeWindt quotes a newspaper account:

The Negro flare-up in 1917 developed from a strike at the Detroit Brass Co., the only industry to hire Negroes. Near the factory were boarding houses and there were loose immoral relations between white and black. The city officials did nothing to stop it. The long festering indignation broke out in mob action.

DeWindt then notes that immoral behavior by African Americans was not the real issue, only an excuse. By 1930, 9 African Americans called Wyandotte home, among 28,368 residents, but 7 were female, and all 9 were probably live-in maids and gardeners. As far as I could determine, Wyandotte condoned no independent black households in the 1920s or 1930s.

104

104

In the 1940s, police arrested or warned African Americans for “loitering suspiciously in the business district” or being in the park, and white children stoned African American children in front of Roosevelt High School. In about 1952, a black family moved into Wyandotte with tragic results, according to Kristina Baumli, who grew up in Wyandotte in that era and is now a professor at the University of Pennsylvania:

After several weeks of hazings and warnings and escalating threats, [they] were killed and found floating in the Detroit River. My family couldn’t give me more details. I asked if they thought this was true, or just a rumor—and they said that were pretty sure it was true, if not well investigated by the police.

More recently, Baumli reports, Elizabeth Park in Wyandotte has been a racial battleground, “where, I’m told, vigilantes enforced the sundown laws extra-legally. I believe the extent of it was just beating people up if they strayed after dark—my impression is that they beat everyone including women and kids.”

105

105

Over the years, then, African Americans repeatedly tried to settle in Wyandotte, only to be repulsed repeatedly. In the 1980s, Wyandotte caved in as a rigid sundown town, but its reputation lingers, and in 2000 it still was only 0.5% black.

ViolenceSimilar series of incidents underlie the zeroes or single digits under “Negro population” in the census, decade after decade, of other all-white towns and suburbs across the United States. Over the years, African Americans have even tried to move into towns with ferocious reputations, such as Syracuse, Ohio: according to a 1905 newspaper report, “two attempts have been made by Negro families to settle in the town, but both families were summarily driven out.” When all else fails, after ordinances and covenants were decreed illegal, when steering, discriminatory lending, and the like have not sufficed, when an African American family is not deterred by a community’s reputation—when they actually buy and move in—then residents of sundown towns and suburbs have repeatedly fallen back on violence and threat of violence to keep their communities white.

106

106

Often the house has been the target. Residents of many sundown towns described incidents involving the destruction of homes newly purchased and occupied by African Americans. Here is a typical account, by a woman who grew up in Brownsburg, Indiana, a few miles west of Indianapolis. She had a conversation with her mother about sundown towns in November 2002 and brought up the topic of sundown signs. Her mother replied, “If you want to know if Brownsburg had them, they did.”

I then asked her about the black family I remembered. My memory was of rumors spreading around my school that they had been chased out by fire. (I thought it was crosses burning or something of that nature.) She said when I was around eleven, a black family moved in and their house burned to the ground.

107

Sometimes the person was the target. If sundown towns have often mistreated transient visitors such as athletic teams and jazz bands, the person of color who comes into a sundown town with the intent to live there has faced more serious consequences. Residents of town after town regaled me with stories of African Americans who had been killed or injured for the offense of moving in or simply setting foot in them. More stories of violence to maintain sundown towns and suburbs have come to my attention than I can possibly recount here; I have posted some at

uvm.edu/~jloewen/sundown

. In one way, all the stories are alike: whites use bad behavior to drive out black would-be residents. Often these stories become active elements of the reputations in ongoing sundown towns and suburbs. In LaSalle-Peru, there is a story about a black family that “moved into town, and shortly after the father was found drowned in the Illinois [River],” according to a woman whose parents grew up there. An African American family moved into Oneida, Tennessee, in 1925, according to Scott County historian Esther Sanderson, “but dynamite was dropped on their house and they were severely injured. They soon left and no others ever came in.” Writing in 1958, she concluded, “There is not a colored family living in Scott County at the present time.” Chapter 7 told that many sundown towns have “hanging trees” that they point out to visitors. Residents of Pinckneyville tell stories of African Americans hanged in at least

three

different places. Even if apocryphal, stories such as these intimidate black would-be newcomers.

108

uvm.edu/~jloewen/sundown

. In one way, all the stories are alike: whites use bad behavior to drive out black would-be residents. Often these stories become active elements of the reputations in ongoing sundown towns and suburbs. In LaSalle-Peru, there is a story about a black family that “moved into town, and shortly after the father was found drowned in the Illinois [River],” according to a woman whose parents grew up there. An African American family moved into Oneida, Tennessee, in 1925, according to Scott County historian Esther Sanderson, “but dynamite was dropped on their house and they were severely injured. They soon left and no others ever came in.” Writing in 1958, she concluded, “There is not a colored family living in Scott County at the present time.” Chapter 7 told that many sundown towns have “hanging trees” that they point out to visitors. Residents of Pinckneyville tell stories of African Americans hanged in at least

three

different places. Even if apocryphal, stories such as these intimidate black would-be newcomers.

108

Residents of sundown towns who hired or befriended African Americans sometimes found that their membership in the white community did not protect them from violent reprisal. In Marlow, Oklahoma, in 1923, a prominent hotel owner was killed because he refused to get rid of his African American employee. “Marlow’s ‘Unwritten Law’ Against Race Causes Two Deaths,” headlined the

Pittsburgh Courier.

“Violation of Ban by Owner of Hotel Leads to Shooting.” Here is its account:

Pittsburgh Courier.

“Violation of Ban by Owner of Hotel Leads to Shooting.” Here is its account:

Marlow’s unwritten law, exemplified by prominent public signs bearing the command: “Negro, don’t let the sun go down on you here,” caused the death Monday night of A. W. Berch, prominent hotel owner, and the fatal wounding of Robert Jernigan, the first colored man who stayed here more than a day in years.They were victims of a mob of more than fifteen men, who went to the hotel where Jernigan had been employed three days ago as a porter and shot them down when Berch attempted to persuade them to desist from their threat to lynch the man.Marlow, one of the several towns in Oklahoma which has not allowed our people to settle in their vicinity for years, has abided by the custom of permitting no members of the race to remain there after nightfall.Last Saturday Berch brought Robert Jernigan here to serve as a porter in his hotel. A few hours later he received an anonymous communication ordering him to dismiss the porter at once and drive him from the city.Berch ignored the letter.The mob went to the hotel early Monday evening, its members calling loudly for the man and announcing their intention of hanging him on the spot.The hotel p roprietor, with J ernigan at his side, hurried into the lobby to intercede, but was shot dead before he could speak. Jernigan also fell, mortally wounded.Their assailants then fled.Mrs. Berch, who witnessed the shooting, said she thought she recognized the man who killed her husband, but authorities Tuesday said they had no clews as to the identity of members of the mob. They were not masked.

Other books

22 Nights by Linda Winstead Jones

The Collection by Shannon Stoker

Forsaken (The Djinn Wars Book 5) by Christine Pope

Rajmahal by Kamalini Sengupta

Athyra by Steven Brust

Mothers and Other Liars by Amy Bourret

Are You Thinking What I'm Thinking? by Belle Payton

My Anchor (Trio Series Book 1) by Blood, Joy

Love on a Deadline by Kathryn Springer