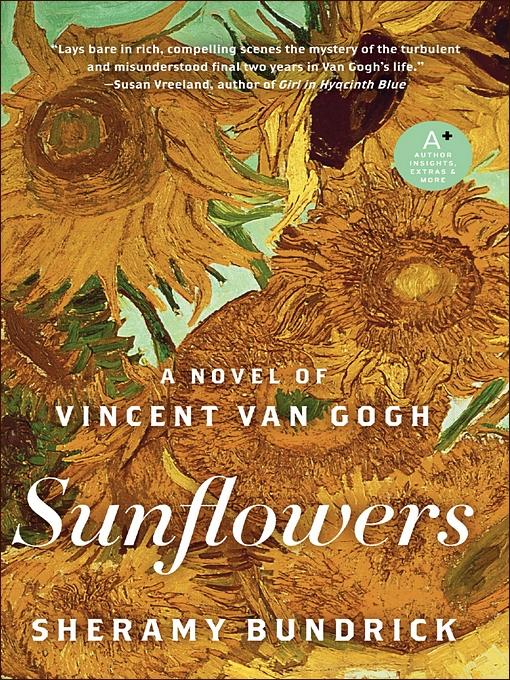

Sunflowers

Sunflowers

Sheramy Bundrick

For my family

and

for Vincent

It is truly the discovery of a new hemisphere in a person’s life when he falls seriously in love.

—Vincent van Gogh

Contents

Epigraph

Chapter One

The Painter

Chapter Two

Vincent

Chapter Three

Le café de nuit

Chapter Four

The Yellow House

Chapter Five

Secrets and Warnings

Chapter Six

A Starry Night by the Rhône

Chapter Seven

The Studio of the South

Chapter Eight

The Alyscamps

Chapter Nine

Absinthe

Chapter Ten

Pastorale

Chapter Eleven

Rain

Chapter Twelve

23 December 1888

Chapter Thirteen

Nightmares

Chapter Fourteen

The Hôtel-Dieu

Chapter Fifteen

Recovery

Chapter Sixteen

Return to the Yellow House

Chapter Seventeen

The Doctor’s Portrait

Chapter Eighteen

Whispers in the Place Lamartine

Chapter Nineteen

Sunflowers

Chapter Twenty

Revelation

Chapter Twenty-One

Relapse

Chapter Twenty-Two

The Petition

Chapter Twenty-Three

Persuasion

Chapter Twenty-Four

Decisions

Chapter Twenty-Five

The First Letters

Chapter Twenty-Six

A New Customer

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Only for the Day

Chapter Twenty-Eight

News from the Asylum

Chapter Twenty-Nine

To Saint-Rémy

Chapter Thirty

Invitations

Chapter Thirty-One

Crisis

Chapter Thirty-Two

The Road Back

Chapter Thirty-Three

The Trains of Tarascon

Chapter Thirty-Four

Seventy Days in Auvers

Chapter Thirty-Five

Paris, August 1890

Chapter Thirty-Six

8, Cité Pigalle

Chapter Thirty-Seven

The Crossroads

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

A+ Author Insights, Extras & More…

Further Reading:

(Partial Bibliography of Works Consulted)

About the Author

Other Books by Sheramy Bundrick

Copyright

About the Publisher

The Painter

Arles, July 1888

I prefer painting people’s eyes to cathedrals, for there is something in the eyes that is not in the cathedral…a human soul, be it that of a poor beggar or a streetwalker, is more interesting to me

.

—Vincent to his brother Theo,

Antwerp, December 1885

I

’d heard about him but had never seen him, the foreigner with the funny name who wandered the countryside painting pictures. Hour after hour in the hot sun, people said, pipe in his mouth, muttering under his breath like a crazy man. Nighttime found him in the cafés clustered around the train station, and some of the girls had spotted him in the Rue du Bout d’Arles, although he’d never visited our house. He was poor, people said. He probably couldn’t afford it.

The day I met the painter, the countryside called me as I would learn it always called to him. Fields and weathered farmhouses lined the road leading out of the city: a half hour’s walk, and I could watch farmers pitch sheaves of wheat into

cabanon

lofts, breathe deeply of air that smelled of harvested grain instead of cheap cigarettes and cheap perfume. Pretend I lived in a cottage framed by cypresses, instead of Madame Virginie’s

maison de tolérance

. That day, the life I led choked me like the heat.

While the other girls napped behind closed doors and shuttered windows, I slipped down the narrow street that followed the old medieval walls, then between the towers of the old medieval gate, the Porte de la Cavalerie. Here on the fringes of Arles lay the Place Lamartine, its public garden ringed by shops and hotels, the road I sought just beyond. A few wagons rattled past, carrying remnants of the morning’s market, and a few stragglers sipped drinks in front of the Café du Prado, fanning themselves with hats. I had sidestepped one of the wagons and was crossing the garden when a loud voice stopped me.

“What is

she

doing here?”

The pair of ladies in their high-collared dresses looked like blackbirds and squawked like hens. “Luc, come to Maman,” the second one called to her little boy from the park bench. “Where are the

gendarmes?

Shouldn’t they protect decent people from such trash?”

A braver girl would have laughed and kept on her way, but I stood stupidly in the middle of the path, glancing from the good ladies to the police station on the other side of Place Lamartine.

Filles de maison

were supposed to stay in the

quartier reservé

, the corner of town where the law put the brothels—I’d be marched back to Madame Virginie’s quick as anything if the

gendarmes

found me. Why hadn’t I pinned up my hair or put on a hat, done something to disguise myself, like any

fille

with some sense?

A policeman!

He had emerged from the

gendarmerie

and was strolling in our direction. The ladies waved their parasols to get his attention, but I bolted before he could see me, ducking through a hedge to another part of the garden. I knew every tree there, every acacia, every pine, and I wove through the grasses to the furthermost edge by the canal, where I sank under a bush and listened for footsteps. No one came. I heard nothing but the bells of Saint-Trophime chiming four and laundresses finishing their work nearby.

“I’m nervous about…you know,” a young voice floated over the splashes. “What do I

do

, exactly?”

An older voice replied, “Lie there and think about the babies you’ll have. It’s not so bad when you get used to it.”

“My man grunts like a pig, I’ve never gotten used to that!” a third woman jumped in, to giggles and more playful splashing.

The soldier I’d entertained the night before, back from North Africa with desert madness in his eyes, had grunted too, like a wild boar rooting for mushrooms. He growled in my ear about what it felt like to shoot a man, and when he was done, he sneered, “What’s with you, girl? Didn’t you like it?” I forced myself to nod yes so he wouldn’t hit me, and even after he left, I couldn’t cry. I crouched in the tin washtub to scrub his sweat away, then tiptoed back to my room and a restless night in the chair by my window.

The tears fell freely now in the garden’s quiet.

What’s with you, girl?

The soldier’s words rang in my head; so did the words of the ladies on the bench.

Decent people. Decent people

. Only when I’d cried all I could cry and was wiping my eyes with the hem of my dress did I listen to the chatter of cicadas instead.

Stay awhile

, they murmured in their buzzing drone,

stay awhile

. The grass was soft and fragrant, the shadow of the cedar bush cool and comforting. It’d be hours before Madame Virginie expected me at supper and Raoul lit the lantern to signal we were open for business.

Sleep

, said the cicadas.

Sleep

.

It took five chimes of Saint-Trophime’s bells to wake me, and I opened my eyes to find I was no longer alone. A man sat under a nearby beech tree with pencil and paper in his hands, face hidden under a yellow straw hat like the farmers wore.

He was drawing me.

His head jerked up when I jumped to my feet, then he stood too, dropping his things to the ground. “Don’t come any closer,” I warned, “or I’ll—!”

“Please, let me explain. I won’t hurt you. My name is—”

“I know who you are. You’re that foreigner, that painter, and you’ve got no right…What kind of girl do you think I am?”

“The kind of girl who sleeps in a public garden,” he said, and he was trying not to laugh. I snorted and took a step toward the path.

“Wait, I’m sorry,” he added. “What’s your name?” He tilted his head and studied me. “I’d guess you belong on

la rue des bonnes petites femmes

across the way, the street of the good little women, as I call it.”

He didn’t seem crazy to me, but still, I crossed my arms and refused to tell him my name. “That’s a silly hat,” I said instead.

He pulled off the yellow straw hat to reveal a ruffled shock of red hair that matched the red of his unkempt beard. Our southern sun had certainly had its way with him, kissing his hair and beard with gold, splashing his nose with freckles. His face had character—a bit serious, with the lines etched on his forehead and mouth drooping at the corners, but not unpleasant. His clothes, though. Blue workman’s jacket spattered with paint, shabby white trousers that needed mending in the knees, mud-caked shoes…

He smiled again, and his melancholy look vanished. “Now will you tell me who you are?”

“My name is Rachel,” I gave in, “and yes, I live on the street of the good little women, as you call it.”

“I’m Vincent,” he said with a bob of the head, “and I am sorry I startled you. I was working nearby, then I saw you and wanted to draw you.”

“What for?”

He shrugged. “You were here, you weren’t moving, and I can always use the practice.”

I held out my hand. “May I see it? I think you owe me that.”

“It’s not very good, it’s just a

krabbeltje

”—he searched for the word in French—“a scribble.” I didn’t budge, didn’t lower my hand. He blushed pink under his freckles, then picked up his sketchbook with a nervous “Careful, it’ll smudge.”

The painter had drawn quickly with his black pencil, but the tangle of lines was me, mussed skirts, mussed hair, face restless in sleep under the cedar branches. I peeked over at him; he was rubbing his shoe into the grass with an expression I couldn’t understand. “It looks like me,” I said politely. “It’s a good drawing.”

His eyebrows shot up. “You think so?”

I flipped through the other pages, some with writing, most with pictures: a man working in the fields, a woman with a baby, a bunch of flowers, a bottle of wine. At the look on his face, I stopped and handed him the sketchbook. “I’m sorry, it’s rude of me to—”

“It’s nothing.” He tilted his head and studied me once more. “Perhaps one day I can paint you.”

“Paint me? What for?”

He laughed. “Because I’d like to, that’s what for. It’s hard finding models here.”

“We’ll see,” I said and backed toward the garden path. “It’s getting late, Monsieur, I should probably—”

The painter bent to gather the rest of his things and looked at me eagerly. “Are you going to your

maison

now? I could walk you, if you like.”

“It’s not far, and I walk alone all the time. But thank you.”

He cleared his throat, the sketchbook now clutched to his chest. “Then can you tell me which

maison

it is? Since you knew who I was, you may have heard I am an occasional patron of

la rue des bonnes petites femmes

, although I have not yet visited your particular establishment. I hope you will permit me to call on you.”

How funny and old-fashioned he sounded, as if we’d be having afternoon tea. “I’d be pleased to welcome you, Monsieur,” I said after the briefest pause. “No. 1, Rue du Bout d’Arles, Madame Virginie’s. Last on the right if you’re coming from the Rue des Ricolets.”

The painter clapped the yellow hat on his head with an awkward bow and a big smile. “I look forward to it, Mademoiselle.

Bonne journée

.”

I nodded in return and walked through the grass toward the Porte de la Cavalerie. Before I ducked back through the hedges to the garden path, I glanced over my shoulder. He was still watching me.

“The greatest city of Roman Gaul,” Papa used to say about Arles, “when Paris was only a city of mud.” The schoolteacher in our village, respectful of history, he wanted to take me to Arles to see the ancient ruins. Maman refused. “Filthy railroad town,” she sniffed, “no place for a little girl.” “There must be little girls in Arles, my dear,” Papa said with a chuckle, but Maman sniffed again, and that was that.

When I finally did step off the train at the Arles station years later, Papa was not beside me. I’d lost him a few months before, Maman before that when I was eleven, and I’d come to the city to begin again, best as I could. An unexpected snowfall had blanketed the buildings in sugary white, and like any

touriste

, I gaped at the Roman amphitheater and medieval bell towers, wishing Papa had been there to see them with me. I gaped at the tourists themselves as they promenaded down the Boulevard des Lices in greatcoats and furs; I gazed in shop windows around the Place du Forum at things I couldn’t afford and wondered how long it would take to find a new life.

But as the days and weeks slipped by and the fistful of francs in my valise melted with the snow, I learned Maman and Papa had both been right about Arles. The city had two faces: the one travelers and rich people saw, and the one everyone else saw, with dingy cafés and tatty backstreets in sore need of sweeping. A girl with no family and no money wouldn’t get very far—no farther, as it happened, than the

quartier reservé

.

That was six months ago.

“Rachel, are you listening to me?”

Friday night at Madame Virginie’s

maison

, and I stood with one of the other girls at the bar, shelving glasses and dusting bottles as the first customers trooped in. Once the most popular

fille

in the Rue du Bout d’Arles, Françoise had a faded prettiness about her that kept her regulars loyal, and a fierce efficiency that kept the rest of the girls in line. She gave me a little frown. “I knew you weren’t listening. Did you read the editorial this morning in

Le Forum Républicain?

”

I shook my head. “What’d it say?”

“The usual thing. Griping how the cafés near the train station are full of whores at night, whining that the

gendarmes

don’t do their job. The town’s infected with a moral plague that must be stamped out!” She made a face and laughed, but I gave the glass in my hand an irritable wipe. Nearly a week, and I still heard the woman in the garden.

What is she doing here?

“That business about the

gendarmes

has nothing to do with us,” Françoise added. “We’re legal. Madame paid good money for her license, and as long as we follow the rules—”

I set down the glass with a sigh. “I don’t want to do this anymore. I’ve had enough.”

“You still fretting about that soldier? Raoul’s got orders not to let him back in, you won’t be seeing him again.”

“It’s not about him. It’s about all of them.”

Françoise put her hands on her hips and gave me the same lecture I’d heard my first night at the

maison

, when I’d balked at the sight of my first customer. Did I want to be a seamstress and lose my sight squinting at stitches? Be a laundress with chapped hands and crooked back? We made a lot more money, she sternly reminded me, and the work was easier than washing clothes in the Roubine du Roi. I should count myself lucky to have a roof over my head and plenty to eat. Didn’t I know other girls starved in the streets?

“Yes, Françoise,” I said, “but—”

“But what?” Her voice calmed. “You’ve had bad luck lately, that’s all. You need more regulars, nice

mecs

who’ll take up your time. But you won’t find them with a sulky face like that.”

“I’m not being sulky, I’m—”

The entrance of a new customer distracted her. “

Tiens

, here comes someone now. Oh, it’s that foreigner. You can do better than that.”

I’d forgotten the painter’s shy wish to visit me and my hasty agreement—I’d even forgotten his name. He’d swapped his dusty clothes for a rumpled black suit, and he carried a black felt hat that looked like it’d seen better days. His unruly hair was slicked back, his beard newly trimmed, and with his hat he held a makeshift bouquet of wildflowers, wilting from the heat. He didn’t look like a man eager to forget a week’s work between a friendly girl’s legs. He looked like a man come courting.

Françoise didn’t notice my smile as the painter gazed around the room and another

fille

sidled up to greet him. “There goes Jacqui,” she sighed. “She’s been here longer than you, she knows damn well Madame Virginie makes the introductions. Poison, that one. I told Madame not to hire her, but she was so bent on getting a blonde in the house when old Louis up the street’s got two.”