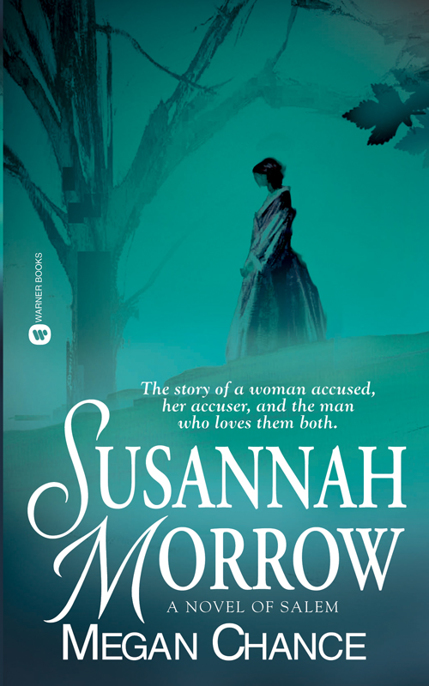

Susannah Morrow

This book is a work of historical fiction. In order to give a sense of the times, some names or real people or places have

been included in the book. However, the events depicted in this book are imaginary, and the names of nonhistorical persons

or events are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance of such nonhistorical persons

or events to actual ones is purely coincidental.

Copyright © 2002 by Megan Chance

All rights reserved.

Warner Books, Inc.,

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

.

First eBook Edition: April 2009

ISBN: 978-0-446-56016-0

Contents

To Kany, Maggie, and Cleo

Without you, there is no story

I’d like to thank my family for their encouragement and support—both financial and emotional; the ever-wise Kristin Hannah,

for her unswerving faith in me; Marcy Posner, who believed in this book from the first moment she saw it; Jamie Raab, whose

editing and enthusiasm have restored my faith in the publishing business; and Frances Jalet-Miller, for her incisive and enlightening

comments. Also deserving of thanks are Jill Barnett, whose generosity is unwavering—I owe her a huge debt; Liz Osborne and

Jena McPherson, who traipsed the countryside and haunted bookstores for me, among other things; and Elizabeth DeMatteo, Melinda

McRae, and Sharon Thomas, who restored my spirit more often than they know.

And finally, I’d like to thank Patricia Krueger, a truly inspiring teacher who went far above and beyond the call of duty,

and Barbara Dolliver, who took the time every other Thursday to teach a fledgling writer her craft—to these two women, my

thanks are long overdue.

From her side the fatal key,

Sad instrument of all our woe, [Sin] took;

…then in the keyhole turns

Th’ intricate wards, and every bolt and bar

Of massy iron or solid rock with ease

Unfastens.…

She opened, but to shut

Excelled her power; [hell’s] gates wide open stood…

—John Milton

Paradise Lost

Not to believe in witchcraft is the greatest of heresies.

—Heinrich Kramer & James Sprenger

The Malleus Maleficium

CHARITY

—Delusion—

We walked in clouds, and could not see our way.

—John Hale

A Modest Enquiry into the Nature of Witchcraft

Salem Village, Massachusetts—October 22, 1691

I

DREAMED THE BABY DIED

.

The vision was still with me when I woke, sweating and uneasy, into a night gripped by a shrieking nor’easter. I told myself

there was nothing to fear as I lay listening to the pine shakes on the roof clattering and creaking. The boughs of the great

oak outside our front door crashed in the wind.

The room was cold, too dark even for shadows. In the trundle bed, my little sister Jude slept on, untroubled. But then, Jude

was not like me; she did not hear souls screaming in the wind. She was only six, too young to know the horror a nor’easter

could bring: animals lost and shattered houses, men drowned at sea. At fifteen, I knew all these things, and so the storm

gave power to my dream.

I did not ignore premonitions. No one I knew did. God sent us signs all the time; ’twas a sin to scorn them. The wheat blight

of a few years ago, the scourge of smallpox that raced through our town, a bird not nesting as it should…These were marks

of His displeasure, and I was a good Puritan girl who knew to pay attention. But I did not know what to do about this one.

I crept from bed, shivering as I worked my way by feel and memory toward the bedroom door. I was trying to decide whether

to wake my mother, when I saw light come through the seams of the floorboards.

’Twas too early for anyone to be awake.

The floorboards were thin—a single layer only, with cracks between that gave a clear view of downstairs. I knelt at the widest

of them, pressing my eye close to the floor to see. I saw my mother bending to the fire, and my father sitting at the nearby

tableboard, pulling on his boots with hurried motions.

The wind howled, and before I knew it, I was out of the bedroom and hurrying downstairs.

I stopped on the bottom step and stayed in the shadows. My mother’s back was to me as she laid a fire in the huge hearth,

and my father was not looking in my direction as he protested in a quiet voice, “…I don’t have time for that now, I’d best

go if I’m to make it back today.”

“’Tis not dawn yet,” my mother said. “We’ve hours ahead of us.” The flames leaped; she straightened and backed away, her huge

belly outlined now in the light. She was not in labor, not yet. I sagged against the wall in relief. The baby was not due

for another month, and everything was fine. It had only been a bad dream, no premonition.

Then she gasped. One hand went to her belly, the other clutched the mantel. I could not keep from crying out. Horrified, I

put my hand over my mouth to stifle the sound. Too late. My parents both looked toward where I stood in the shadows of the

stairs.

“Charity?” my mother asked softly. “Is that you, child?”

I hurried toward her. “Oh, tell me ’tis not the babe coming already.”

My mother smiled. I knew she meant to be reassuring, but I saw her strain. I saw her hope and her fear. “Aye.” She reached

out and held me close enough that I felt the movement of the child through her skirt. Her hand rested lightly on my hair,

and I closed my eyes, comforted at the feel of it, at her familiar smell—fire smoke and the mint and sugar she burned on the

hearth to scent the room. She nodded to my father, who still sat at the table. “Your father’s going to town.”

I pulled away in confusion. “To town?”

“To fetch your aunt,” Mama said gently. “The

Sunfish

came in yesterday. She’s waiting.”

I turned to my father. “W-what about the storm? Who’s to fetch Goody Way? And the others?”

“You needn’t worry about the storm,” Father said. “You help your mother.”

I felt panicked. “But I had a dream.…”

“Hush, hush,” Mama said, reaching for me again. When I pulled away, she sighed. “’Tis only the storm that has you so upset,

child. There’s no need to worry. Your father will wake Prudence Way before he goes. She’ll bring the others. ’Twill all work

out. ’Tis good you’re awake. You can help with the groaning cake.”

I looked to my father. “Can’t Aunt Susannah wait another day? At least till the babe’s born and the storm’s passed?”

Father gave me a look I knew too well, the one that made me flush and stutter and wish I’d kept quiet in spite of my worry.

’Twas not my place to question him, and I looked away again, wanting still to protest, holding back my words.

My mother made a hiss of pain.

“Mama,” I said, “you should sit down.”

“Standing makes the child come faster,” she said when she could breathe again, and then she smiled, but she glanced over at

my father, and told him, “You’d best tell Prudence to come quickly.”

He stopped. “Perhaps ’tis better if I stay, Judith. Your sister will wait another day.”

“No, no,” Mama said quickly. “Eighteen years have already passed. I’d not have another needless hour between us.”

I held my breath, waiting for my father to remember Mama’s other labors, the terrible small graves dotting the thick, wild

grass of the burying ground.

He will refuse to go.

The storm was bad, and Mama’s labors were always so hard, and the babe was too early besides. I willed him to stay with all

my strength.

“I’ll do my best to hurry.” He paused at the door, staring out the window as he grabbed his cloak and his hat. “’Tis as if

God put His hand over the sun,” he murmured. Then, in a swirl of movement, he was out into the night, and my mother and I

were left alone with the fire and the sizzle of rain falling down the wide chimney, while little drafts of wind sent the thin

coarse linen of my chemise shivering against my legs.

“Get dressed, Charity,” my mother said. “The storm will be over soon, and we’ve the baking to do.”

As the hours passed into morning, and then into early afternoon, neither the storm nor my dread eased. Even when Goody Way

showed with the other women from the village—windblown and shivering, soaked through to the skin—I was not reassured.

The women gathered around, eating groaning cake and drinking beer from the pewter tankards we’d set on the table, joking and

exclaiming over how tall Jude had grown, but for me, a laying-in had long ago ceased to be a celebration, and I wanted them

to go home. All I really wanted was for my father to come through that door again.

He should not have gone. We had not been expecting this aunt I’d never met for another two weeks at least; the

Sunfish

had made the journey from Dover more quickly than we’d imagined, especially for the time of year. It would not have hurt

to make her wait.

My mother’s pains grew slowly worse; I watched her carefully, waiting for the first sign that something had gone wrong. Experience

had taught me that there was always a moment when everything turned, when things went bad, but even as the hours passed—nearly

an entire day now, already suppertime again—and my mother’s labor grew harder, and we moved into the parlor where the big

bed she shared with my father loomed in the corner, that moment had not yet come. Goody Way had not yet started the slow,

worried shaking of her head that had grown as familiar to me as the beating of my heart.

It grew late again, and I put little Jude to bed; she was a heavy sleeper, and Mama’s screams would not wake her. The storm

had begun to ease, and the women drifted away, one by one, fetched by their children or their husbands. Goody Way let them

go, because Mama’s labor was dragging on and on, and they could do no more good here. Without them hovering around, shooing

me out of the way as if I were a small child instead of a woman nearly grown, I could come close to my mother again. I sat

down beside the bed, holding her hand. She gripped my fingers tightly.

“The babe is fighting me,” Mama said, smiling weakly at me. “It must know the sorrow of the world already.”

“It sounds like a good strong boy,” I said, hoping it was true. “I should like a brother, I think.”

Mama started to smile, and then the pain gripped her, and instead she groaned; she squeezed my hand so hard it seemed my bones

would pop beneath her grip. Sweat dripped down her face; her hair was wet and coarse with it.

“Can you walk again, Judith?” Goody Way asked from where she sat at the end of the bed, between my mother’s spread legs. “’Twould

help.”

Mama nodded and grabbed my arm, but the moment she was out of bed, her knees buckled, and I saw the sudden blot of blood color

her chemise. I saw her belly ripple and misshape with the strain, and I knew.…This was the moment I’d feared. I glanced up

and caught Goody Way’s gaze, and there it was—the slow shake of her head—and I knew my dream was coming true. The babe was

dying. I felt sick for the hope Mama had had for it. I did not know if she had the strength to bury another infant.