Swastika (3 page)

“Something different,” Chandler said.

“I don’t get many stakings. Vampires are foreign to this part of the world.”

“Missed the heart by a mile.”

“Don’t touch the stake,” cautioned Macbeth. “There’s blood up on the handle.”

The pathologist had moved back to let the inspector squat near the body. Crouched on the balls of his feet, Chandler felt the earth vibrate as heavy rigs crossed the overhead span. The Congo Man was sprawled face up on the bank, with his crown toward the arch support and his soles toward the creek. With arms as big as other men’s legs, a chest the size of King Kong’s, and a skull that seemed to reduce a bowling ball to the girth of a pea, he was a giant of muscular power. Tussling with him, Chandler had thought yesterday at Colony Farm, would be like having Tyson going for your ear.

“Cause of death?” he asked Macbeth.

“His skull was caved in with a blunt instrument just before he was spiked through the eye. See how splinters of the zygomatic arch sink into the socket around the stake? Someone approached him with a weapon in hand, clubbed him across the side of the head, shattering his skull, then rammed the stake into his eye after he hit the ground.”

“Dead either way?”

“Uh-huh. He was probably in his death throes when he was spiked to the earth.”

“What sort of blunt instrument?”

“It could be the stake. The handle’s made of wood, but the lower shaft is metal.”

“Like the head of a spear?”

“It’s about the length of a walking stick. The killer would seem to be hiking as he approached, then suddenly the walking stick would turn into a baseball bat. A whack across the side of the head and down would go the giant. Plunging the tip into his eye socket would spike him to the ground.”

“Wicked.”

“And effective. Three tools in one.”

“The killer’s lucky the bat didn’t break.”

“But unlucky if the blow cracked loose this splinter.” Gill pointed to a sliver of wood still attached to the handle. “See the blood on the tip? That could be from the killer. Even wearing gloves, he might’ve pricked his hand as he drove the stake through the skull. Perhaps he didn’t notice at the time.”

The Congo Man wore a black patch over his other eye. He looked like a pirate who had seen his last doubloon.

“Check under the patch?”

“The eyeball is missing. Probably lost it in the Liberian civil war,” said Gill.

“Anything else?”

“Examine his forehead, Zinc. You’ll find a possible motive hidden in the blood.”

The Congo Man’s face was a mess of gore. Blood had bubbled out of the spiked socket like an erupting volcano. The red lava had begun to clot on his black skin. Moving in for a closer look, the inspector breathed in the sweat of insanity wafting up off the cadaver. Then he discerned the symbol that had been carved into the forehead of the African refugee, above and equidistant to the pirate patch and the vertical stake.

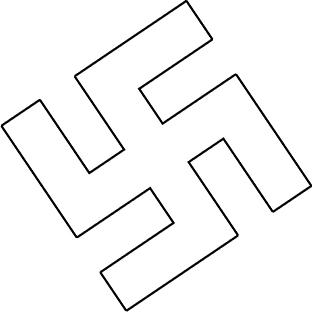

The symbol, covered with blood, was instantly recognizable:

“Motive?” Chandler asked, glancing up at Winter.

“Hate crime? Possibly. Lots of hate around. Sikh stomped to death by skinheads outside his temple. Jewish graveyards desecrated. Refugees waylaid. Cole might have been sleeping rough under these spans when a neo-Nazi gang chanced along.”

“Or?”

“Or the swastika might be a red herring. Someone killed him for a personal motive and masked it as a hate crime.”

“To avenge the dead girl?”

“Perhaps,” said Winter. “Or it could be a hit gone wrong. The Ripper enlisted the Congo Man to kill you. Maybe Cole teamed up with a partner, and they had a falling-out.”

“Who found the body?”

“A jogger with a wayward dog. He’s clean.”

“That’s several leads. It’s your case, Sergeant. Where do you plan to start?”

“Feel like a drive?”

“Where to?” asked Chandler.

“Inland to Colony Farm.”

* * *

Cort Jantzen, the crime reporter for

The Vancouver Times

, waylaid them as they crested the path to their cars.

“Is it true that the vic is the cannibal killer who got released yesterday because of a foul-up by the courts?”

“I wouldn’t put it that way,” Winter replied.

“Is the vic Marcus Cole?”

“Yes,” responded Chandler.

“Do you suspect that an outraged relative of the cannibalized girl took justice into his own hands?”

“The investigation is ongoing. No comment.”

“A vigilante?”

“No comment,” echoed Chandler.

“The jogger who found the body says it was nailed to the bank by a stake that had been rammed through the head. Do you have any reason to suspect it’s a hate crime?”

“We have inquiries to make,” said Winter. “Media Relations will issue a press release.”

They left the reporter scribbling empty words in his notebook. For decades, the Mounties had used “key-fact hold-back” evidence as a sneaky trip-up tool. Key facts known only to the primary investigators and those involved in an offense were held back from the media as a means to weed out false confessions and expose those with

inside

knowledge of the crime. In this age of the Internet and people willing to say and do anything for their fifteen minutes of fame, key-fact hold-back evidence was even more crucial.

Cort Jantzen had been closing in on the key fact in the Congo Man killing when the cops had ducked away. They didn’t want him to catch them on record with a lie.

The key fact was the Nazi swastika that had been carved like a Cyclops’ eye into the cannibal’s forehead.

Port Coquitlam

The traffic out here is a nightmare. Geography creates it. Vancouver sits at the mouth of a river that cuts west to the ocean through a north-south range of mountains. Exacerbating an already tight situation, the Pacific balloons inland, creating a major harbor. For physical setting, there are only six great cities in this world: Hong Kong, Sydney, Cape Town, Rio de Janeiro, San Francisco, and Vancouver. Cram a million outdoorsy Lotuslanders onto a few geographically bottlenecked arteries and the bumper-to-bumper gridlock is enough to enrage even the most laid-back tree hugger.

“Man,” said Winter, banging his palms against the steering wheel as if that would make the car move faster, “I could live two lives with the time I waste on this highway.”

“Try yoga,” said Chandler soothingly.

“If this keeps up, I’ll try my nine-mil instead.”

“Cars with dead drivers. Somehow I doubt that will help.”

From the North Shore murder scene, they had U-turned south on Fell Avenue to bridge Mosquito Creek by the lower road, before angling back up to the Trans-Canada Highway. Cutting east across the mountain slopes and fording the harbor on the Ironworkers’ Memorial Bridge—the building of which had cost twenty-five lives in four accidents, inspiring the 1962 hit “Steel Men” by Jimmie Dean—had put them onto this snail trail up the Fraser Valley. Cars inched forward on this highway toward urban sprawl. Finally, just before another bridge stepped across the mighty Fraser River, they branched off onto the old Lougheed Highway, which ran parallel to the freeway. Ahead, in the crook where the meandering Coquitlam River snaked south to empty into the headwaters of the Fraser Delta, stretched the marshy flatlands of Colony Farm.

“Your family name’s Winter?” said Chandler. “Are you one of the Air Division Winters?”

“My dad and my granddad. Not me,” Dane replied.

“That must have been hard on you. Losing your parents and your grandmother in a single crash.”

“I was young. Somehow that cushioned the blow. It was worse for my granddad. He lost his wife, his only child, and his daughter-in-law in the blink of an eye. All he had left was me.”

“Still living?”

“No, he died on Wednesday. Tomorrow morning, the undertaker will deliver his ashes to me.”

“Sorry to hear.”

“In the end, it was a blessing. Pancreatic cancer is an ugly route to go.”

“I loathe hospitals.”

“So did my granddad. Until just before the end, he wasted away in the house he purchased fifty years ago.”

“Sounds expensive.”

“It was,” replied Dane. “I had to create a mini hospital at home for him. Now I’m in the process of cleaning it out. I feel like I’m working an archeological dig. All those layers of family history. Last night, I came across his pilot’s flying log from the war. He flew fifty-plus bombing missions over Nazi Europe and North Africa. Ironic, huh? The odds of his surviving the war shrunk to about one in forty. The Nazis couldn’t get him, and he came back. Then Mother Nature got his family on a

civilian

flight.”

“Hit the Razorback, right?”

“Yeah. Up the valley. Several miles east of here. Strange, but I’ve never been up to the Mountain. I was too young for the memorial service at the time of the crash, and then … well, it’s like I have a psychological aversion to the place.”

“Perhaps one day?”

“Oh, it’s gonna happen. Sooner, not later,” said Dane. “Depending on the weather and the avalanche warning. Within a day or two, I have a date with the Mountain.”

* * *

It used to be that you would turn south toward the Fraser River off the Lougheed Highway onto Colony Farm Road to drive the eeriest mile on the West Coast down to the Riverside Unit for the criminally insane. Back then, the hills surrounding the murky marsh were thick with primal woods, and the right side of the road was overhung by a line of towering elms. Colony Farm dated back to the era when masturbation was thought to be one of the four causes of insanity, and the haunted-house asylum at the end of that postcard-perfect byway seemed fit for the likes of Karloff and Lugosi. In fact, mad scientists did once work for Riverside, lobotomizing patients with razor-sharp scalpels and unscrambling fried brains with jolts of electricity. One look at that Gothic madhouse, with its crosshatched bars on triple tiers of windows along both wings and black crows perched on the eaves of its flat roof, and you could imagine the screams of those long-ago inmates.

The flip side of that historical coin was Colony Farm today. Gone was the wooded landscape around the marsh flats; now god-awful monster houses blighted the denuded hills. Root rot from neglecting the drainage had toppled most of the elms, so swaths of sunlight played across the roof of the cop car as it closed in on the vacant riverside lot that once had housed the decrepit asylum. The replacement for that archaic booby hatch was the $60-million Forensic Psychiatric Hospital. Just to the right of the demolished institution spread a spacious lot where Winter parked the car.

“It looks like a country club,” he said.

“That’s the idea.”

“Fancy a round of golf?”

The gate was forged from vertical bars that were strengthened with a bull’s-eye circle. The lawns beyond were as manicured as putting greens. From the hub of a central hall, where the patients attended school and chapel, a ring of spoke-like paths radiated out to the patient residences. The structures were named Fir, Cottonwood, Dogwood, Birch, and so on. The administration building—Golden Willow—flanked the gate. Opposite it, on the right side, sat the stronghold of Central Control, beyond which was hidden Ashworth House, where the high-risk psychos were caged.

Psychos like the Ripper.

And until yesterday, the Congo Man.

“Back so soon?” the security guard asked Chandler.

“Unfinished business.”

The inspector and Winter signed the visitors’ log and handed in their guns.

The nurse who came to fetch them was Rudi Lucke. Meticulous, wiry, fine-boned, and in his mid-forties, Rudi had given the Congo Man his nickname. Years ago, at Carnival in the Caribbean, “Congo Man”—the calypso tune by Mighty Sparrow—had caught Rudi’s ear. Because the lyrics about never eating white meat seemed to fit the crime that had sent the Liberian refugee to FPH, Congo Man was the ideal sobriquet for Marcus Cole.

Yesterday, Rudi had informed Chandler about the Ripper’s refusal to see him, just before pointing out the conspiratorial meeting between those psychos in the yard. Today, from the look in Rudi’s eye, Chandler knew the nurse suspected why the Mounties were here.

“The Ripper?” Rudi inquired.

“Yes,” said Zinc.

“His body is in his room. Don’t know about his mind.”

Buzzing the key reader with his fob—the personal electronic pass that registered who opened which door at what time in Central Control—Rudi led the cops through a security door that led to an interview room. The hall, with its cinder-block walls and window slats instead of bars, seemed common enough. But those blocks encased a steel grating that turned the hall into a cage. The “glass” was really Lexan, an unbreakable polycarbonate resin, and rotating rods were hidden within the slats to foil the bite of hacksaw blades. The pen in Rudi’s pocket was an alarm. Triggering it would bounce a beam off the peach walls and peach floor with its blue stepping-stone squares to a sensor on the ceiling that would summon the entire staff of Ashworth House within thirty seconds.

You couldn’t be too careful with psychos like the Ripper.

The interview room, eight feet by ten, was starkly furnished with a table and two chairs. The sterile box had no art or atmosphere. The door didn’t lock.

“He might not see you,” Rudi said.

“Bring him anyway,” replied the inspector.

* * *

For Rudi, it was the eyes.

It bothered him that he judged people by a physical characteristic, but the eyes were different, weren’t they? The windows of the soul? Eyes weren’t like noses, cheekbones, and lips: racial characteristics. Eyes—the eyeballs, at least—were more than that. “If thine eye offend thee, pluck it out …”

But still he felt guilty.

His guilt, he suspected, went back to something his grandfather used to say about reading the eyes of the Nazis in order to stay alive in the camp. Lucke was a name with centuries of Jewish history in Prague, so when the Aryans occupied Czechoslovakia during the war, “Good Lucke,” the old man said bitterly, “won me a trip to Terezin.”

Terezin, a concentration camp north of Prague, had been established in a fortress from the eighteenth century. During the trip there, the Gestapo had stopped the truck convoy of political and Jewish prisoners on an old stone bridge across the Vltava River. They selected five men from each transport group and had them line up along the plunge to the water. Next, they looped a double noose around the men’s necks, joining the five chosen Jewish prisoners to the five non-Jewish political prisoners, who were then shot in the head. As each dead man tumbled toward the river below, the still-living Jew was yanked off the bridge and into the water like jettisoned cargo weighed down by a human anchor.

“We don’t waste bullets on Jews,” the SS commandant warned the convoy prisoners.

To this day, Rudi couldn’t glance over the side of a bridge without momentarily glimpsing phantom eyes staring up from the depths of the water.

Once at Terezin, however, the SS had no qualms about wasting bullets. Prisoners who tried to escape were stoned to death in the courtyard, and others were locked together a hundred at a time without food and water in a cramped room where the SS could watch them die. But past the quarters where the commandant and the ranking guards resided was a target range. There, Jews were forced to run from one side of the yard to the other so the SS could enjoy shooting practice.

“You can spot a Nazi by his eyes,” Rudi’s grandfather maintained. “I survived the camp because I learned to read their eyes. Nazis escaped after the war and are hiding around the world. Study their eyes, Rudi, so that you can spot them too.”

On Saturdays, it was Rudi’s chore to accompany the old man to the library. He would lean on the boy and hobble along the street with his cane. Inside, they would find a book on the Third Reich and sit together at a reading table to study the eyes. Hitler’s eyes, flashing as he shrieked fiery oration. Himmler’s eyes, as cold as ice behind his wire-rim glasses. Göring’s eyes, in that piggy face. Eichmann’s eyes, in Israel, on trial in the glass booth. Streicher’s eyes, in one of the few photographs of him to survive the war.

One day, they had shared their table with a blond man who was also reading a photographic book on the Second World War. “What they did to us was awful,” said Rudi’s grandfather, rolling up his sleeve to expose the number tattooed on his forearm, “and pictures cannot capture the torment we endured.” Frowning, the stranger set his book down on the table, and Rudi saw the photo that he had been perusing. It was of a Nazi with a weird measuring device, some sort of calipers he was applying to the face of a Jew to prove him “subhuman.” Then Rudi noticed the blond man’s eyes. He wasn’t looking at the tattoo on his grandfather’s arm. He was staring intently at the old man’s nose.

Rudi felt suddenly guilty.

For staring as unreasonably at the stranger’s eyes.

Decades had passed since then, but Rudi’s ocular compulsion had not. Some days he was convinced that was why he had sought this job as a psychiatric nurse in Ashworth House. The link went back to the trial of the Manson Family in 1970, when Charles Manson and three female disciples, Susan Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel, and Leslie Van Houten, had carved swastikas into their foreheads as they prepared to face the jury judging them on multiple counts of murder. “I have X’d myself from your world,” that hypnotic guru had declared. Rudi had stared, transfixed, at newspaper photographs of Manson’s maniacal eyes looking out from under the swastika he’d gouged into the flesh above his nose.

The killer had Nazi eyes.

The eyes of those in Ashworth House were haunted by psychosis, and none were more unfathomable than those of the psycho in room A2-13. Before he entered the Ripper’s realm in the high-security ward, off a hall that was constantly monitored by watchers in the fortified nursing station at one end, Rudi peeked in through the oblong judas window in the blue door. Though the ward was sealed, the door wasn’t locked. The Forensic Psychiatric Hospital wasn’t an asylum, and its patients were free to leave their rooms to go to the toilet, the dining room, the TV room, the smoking room, and the quiet room for reading. The Ripper, however, rarely left his realm, except to travel.

To time-travel back to London.

To 1888.

Five inches wide and three feet tall, the judas window was a slit in the door. Positioned near the handle, it gave Rudi an overall view of the room, except for the corner by the hinges. A bed with a brick headboard was bolted to the left-hand wall. The Ripper lay stretched out on it with his feet in the far corner. Scrawled on the wall beside his head were Einstein’s theory of relativity and jottings from Hawking’s

Brief History of Time

. The notes segued into a jumble of occult symbols that spiraled like a time tunnel from the Ripper’s insane mind across the opposite wall, to end in a mishmash of morgue photos and maps on the right-hand wall. The big map was of the East End of London in 1888. Marked on it, and detailed by smaller maps, were the five spots where the notorious Jack the Ripper had struck. Surrounding them were morgue photos of his victims, slashed to ribbons, disemboweled, and relieved of various organs. And ringed around all that, to represent the mouth of the time tunnel, was a deck of occult tarot cards.

Rudi opened the door.

The Ripper didn’t move.

He must be off time-traveling through the wormholes bored into his diseased brain, thought the nurse.

“There’s news,” Rudi announced.

The Ripper didn’t stir.

“Marcus Cole,” he suggested.