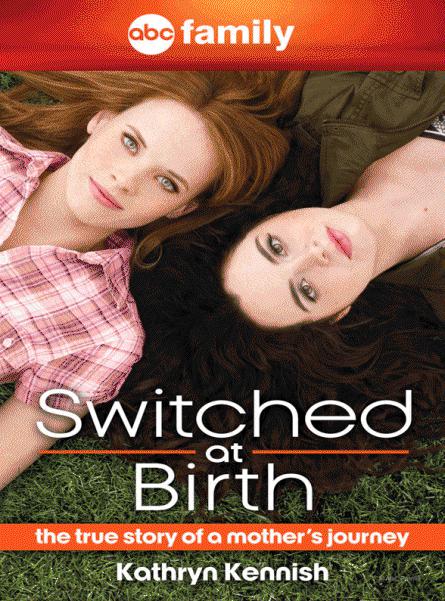

Switched at Birth: The True Story of a Mother's Journey

Read Switched at Birth: The True Story of a Mother's Journey Online

Authors: Kathryn Kennish,ABC Family,

To all the people who have given me hope and guidance on this journey, especially my family—John, Toby, Bay, Daphne, Regina, and Adrianna.

Prologue

When I sat down to begin this book, to tell my story to the world, I thought that I would write about how a family was turned upside down and still managed to land on its feet.

To a large extent, that’s what I have done. But in the process, I’ve discovered that landing on our feet was only the first test. The real trick is going to be staying there.

The people you will meet in this humble memoir of mine—my husband John, my daughter Bay, my other daughter Daphne, my son Toby, and Daphne’s mother Regina (to name only the main players)—are in danger every day of losing the very precarious footing we’ve established. Imagine turning cartwheels during an earthquake—that’s what we were up against, what we continue to be up against, and sometimes it seems like the aftershocks will go right on shaking us for the rest of our lives.

But we haven’t given up yet, and I think that says a lot about us. But not all.

So in the following pages I will reveal to you the events and the emotions, the accidents, the errors in judgment, and I will endeavor to explain to you how these moments have defined who we are and the paths we have taken. I think you will all relate to the challenges I’ve faced, even if your children weren’t switched at birth.

And if, by some chance, they were, then this is definitely the book for you.

I may not have

the

answers, but I do have

my

answers, and if mine can, in some small way, help lead you to your own, then I’ve accomplished what I’ve set out to do.

This book contains my advice for those who find themselves doing cartwheels in an earthquake, turning somersaults in a storm. Sooner or later you

will

land on your feet. And when you do, stand strong.

I promise you, you’ll make it.

Kathryn Kennish

You marry a man—not just

a

man, but your dream man—and together, you plan things. Like where you will live, the kind of carpet you’ll have in the family room, how you’ll invest your money. But most of all, you plan your family. The word itself, when you finally find the courage to say it out loud, is nothing short of magical. At first you concern yourself with the practical things, like whether or not you’re financially prepared for such a life-altering undertaking. But once you’ve decided you’re ready, you begin to imagine in a million different ways the children you will bring into the world. You find yourselves whispering names to each other, trying them out to see how they will sound when cheered at the top of your lungs from the bleachers at the big football game. Or when announced over the PA system at the commencement ceremony of some Ivy League school. You wander into the baby furniture store and tell the clerk you’re just looking, but the truth is, you already know exactly which crib you want, and exactly where it will be placed in that big, sunny room at the end of the upstairs hall.

And after the planning comes the wondering: Will our baby have my eyes? Will she have my husband’s gift for sports? My love of anything chocolate?

You plan, and you dream, and you hope and you wonder.

And then one day, after the longest (and somehow, shortest) nine months of your life, you get to take part in a miracle. It’s a blur of pain (which you promptly forget) and joy (which you remember forever). And then, suddenly you’re cradling a tiny bundle in your arms.

Your daughter.

You feel overwhelmed and overjoyed at the same time. And now you’re

wondering

again: Is she warm enough? Am I holding her too tightly? Has my husband installed the car seat exactly as described in the instruction manual? He has, of course, because you made him go over the diagram a thousand times, but still, you wonder....

You wonder if you have enough diapers waiting at home; you wonder how her big brother will react when he sees her for the first time; you wonder if she will be a good sleeper, a fussy eater, colicky, calm? Will she be musical, artistic, athletic?

But the one thing you absolutely do

not

wonder … not for one moment, not even for a single heartbeat, as this tiny, precious baby girl clutches your thumb and gazes up at you with absolute unconditional trust … the one thing you do not wonder is if she is

yours

.

Perhaps somewhere, someone has done the research, has calculated the precise odds of a newborn child in the United States of America accidentally being given to the wrong parents. I suspect the likelihood is similar to the chances of a person being struck by lightning. Virtually nonexistent. A near impossibility.

Well, this is my story—the story of me and my daughter, of my husband and my son and of two perfect strangers. It is the story of how one day, sixteen years ago, without notice, without warning, we were all struck by lightning.

It began with, of all things, a science project.

My daughter—my beautiful, dark-eyed, raven-haired daughter, Bay—had discovered through a lab experiment in science class, that her blood type was AB. For most people, being AB would be considered rare. For Bay, the daughter of two type A parents, it was genetically impossible. Naturally, my husband John and I simply chalked it up to an error, a mistake. Bay wasn’t a kid with a particular gift for science after all; she was an artist. A great kid, a smart kid, but to our everlasting frustration, a kid to whom school was not a top priority. Which was why John and I were so easily inclined to shrug off her AB findings as merely Bay not giving the work her full attention. Obviously, she had misinterpreted the data.

But Bay felt differently. She was, if not freaked out exactly, troubled by the results. On our drive to school that morning—after Bay revealed the news about her blood type at breakfast—she reminded me, not unkindly, that she and I had almost nothing in common. Then I reminded

her

that this was due to the fact that she was a teenager and therefore if she did have anything in common with me, she’d be laughed right out of high school.

Maybe it was at this point that some tiny seed of panic began to form deep, deep within me. I don’t know now, and I may never know. If I did feel something, I do know that I ignored it. If I sensed it—some small, gnawing sense that perhaps, just perhaps, something really wasn’t adding up—I tamped it down.

Denial? Maybe.

Terror? More likely.

Because I was happy.

We

were happy. The Kennishes were happy and

whole

, and we would always be exactly as we were, as we’d always been.

God, how wrong I was.

As we drove toward school, Bay went on to muse over the fact that her coloring and her body type were nothing at all like mine. And then she admitted, haltingly, in a tone I’m sure she’d meant to sound indifferent but that to a mother’s knowing ear echoed with deep curiosity and no small amount of worry, that she’d been teased more than once about being adopted.

That nearly floored me.

Adopted.

It was not a bad word, of course. It was a lovely word. It just wasn’t a word I’d ever had cause to apply to my family. Our family. I gave birth to two beautiful, healthy children—Toby and Bay. I held them seconds after they were born, nursed them, loved them. And as I jokingly told my daughter that morning, “I’ll show you my stretch marks.”

I remember she didn’t laugh.

“So we don’t look alike,” I conceded. I explained to Bay that as evidence went, this meant nothing. I, a strawberry blonde, had always taken a

vive la différence

stance when it came to the physical attributes of my little girl. I loved her glossy black hair and envied the way it tended to curl—unlike mine, which required boatloads of product to muster so much as a wave. I’d always bragged that her deep, dark chocolate eyes were her most beautiful feature. And I told her what I’d always believed—that her skin tone and dramatic hair color were attributes passed down to her from my Italian grandmother.

But Bay still seemed bothered by the whole AB thing.

So, thinking almost nothing of it, John and I agreed to put her concerns to rest by taking a blood test—a real one, the kind that goes beyond a high school science experiment. We agreed to the test for the same reason that we agreed to let her decorate her room in the style of Jackson Pollock when she was eight years old—because it really didn’t seem like a big deal to us, but it did matter an awful lot to her.

So we said, “Sure. We’ll take the test.”

In the case of Jackson Pollock, let’s just say that John and I were mildly shocked to walk into Bay’s bedroom and find not only the walls but the floor, the curtains, the bedspread, and Bay herself splattered with splotches of bright red, blue, and yellow paint.

In the case of the blood test, the shock level went way beyond mild.

Because the follow-up testing, to which John and I had so casually, carelessly agreed, proved something that neither I nor my husband would have ever imagined.

It proved something that Bay had secretly feared, as it turns out, since long before she’d ever set foot in that science class, and it proved it conclusively. Irrefutably.

It proved that she wasn’t ours.

Let me say that again, because it bears repeating. God knows, I repeated it myself a million times in those first few days after we found out. I repeated it out loud, and in whispers; I hissed it through gritted teeth and howled it on the heels of heart-wrenching sobs. According to John, I even mumbled it on more than one occasion while thrashing around in my sleep:

Bay. Wasn’t. Ours.

The test proved it. The daughter I had loved, admired, fretted over, scolded, hugged, nagged, and adored for sixteen years had absolutely no biological connection to me, or to my husband, or to our son. It was unthinkable. Unspeakable. But it was true.

So here is some advice: If your children, like mine, ever complain to you that what they’re learning in school is a bunch of irrelevant stuff that they’ll never use “in real life,” well, you can tell your kids for me that they are wrong.

Flat-out wrong.

Because what my daughter learned in school that day went way beyond relevant. And as far as “real life” is concerned, not only did this information apply directly and profoundly to our real lives, it actually redefined them.

The baby girl I had brought home from the hospital and placed gently in that crib in the big sunny room at the end of the upstairs hall was not the baby girl to whom I had given birth.

For a long time after the switch was revealed, people would ask me how I was dealing with it.

They would ask me that question in a tone that was part compassion, part fascination.

How are you dealing with it?

they wanted to know.