Sword of Hemlock (Lords of Syon Saga Book 1)

Read Sword of Hemlock (Lords of Syon Saga Book 1) Online

Authors: Jordan MacLean

Tags: #Young Adult, #prophecy, #YA, #New Adult, #female protagonist, #multiple pov, #gods, #knights, #Fantasy, #Epic Fantasy, #Magic

Published by Raconteur House

Manchester, TN

Printed in the USA through Ingram Distributing.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and

incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used

fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business

establishments, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

SWORD OF HEMLOCK

Lords of Syon Book One

A Raconteur House book/ published by arrangement with the

author

PRINTING HISTORY

Raconteur House ebook edition/February 2013

Raconteur House mass-market edition/April 2013

Copyright © 2013 by Jordan MacLean

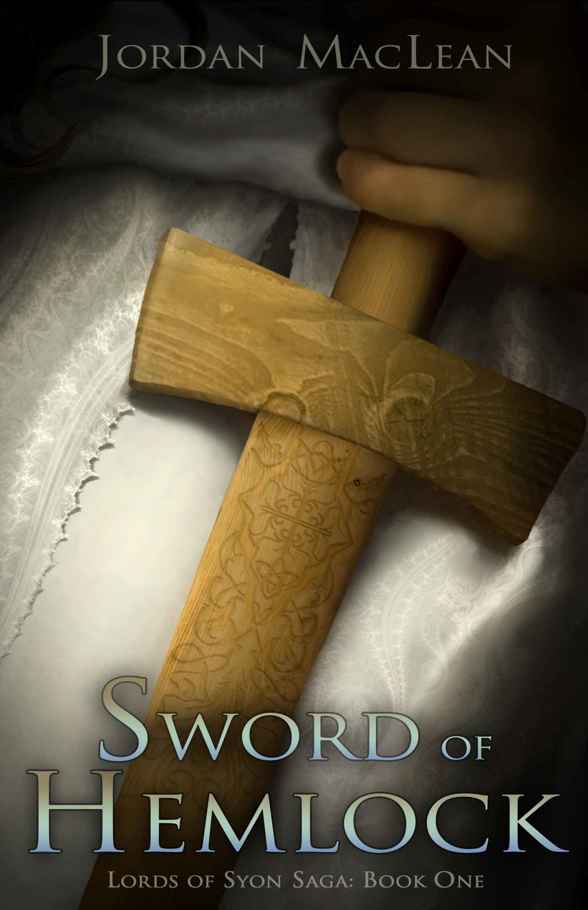

Cover by Katie Griffin

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or

distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not

participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials in

violation of the author’s rights.

Purchase only authorized editions.

For information address:

Raconteur House

164 Whispering Winds Dr.

Manchester, TN, 37355

ISBN: 978-0-9853957-8-0

If you purchased this book without a cover, you should be

aware that this book is stolen property. It was reported as “unsold and

destroyed” to the publisher, and neither the author nor the publisher has

received any payment for this “stripped book.”

For Mike and Jericho

Castle Damerien

in the year of Syon, 3845

T

he

knight took the gold ladle from the vestibule fountain and gulped down the cool

water with abandon, letting it splash down his chest to the stone floor. He

was scandalously underdressed in only breeches and a loose shirt, but he’d

ridden light, opting for speed and comfort over propriety. Besides, better

that no one in passing could mark him as a Knight of Brannagh—much less as the

sheriff himself—especially if they guessed that he was headed to Castle

Damerien. He would not feed their rumors and fear mongering.

He scooped up another ladle’s worth, and, resisting the

battlefield habit of pouring it over his head, he drank it off again, meanwhile

taking in all the familiar sights and sounds of his boyhood home. Behind him,

his father’s retainer heaved closed Damerien’s great keep doors against the

mid-season heat, and all at once rich smells of roasting meats and baking bread

filled the air from the kitchens below.

A celebration, then. But he dared not to hope.

“Nestor.” He smiled, clapping the old servant

affectionately on the shoulder. “I trust you are well.”

The old man bowed. “Well as can be expected, Lord Daerwin,”

he burred softly. Nestor’s long hair was pure white now, instead of the waves

of smoke and fire the young lord remembered so fondly from boyhood, and he

walked with a marked hobble in his step. Beneath these outward shows of age,

however, the old Bremondine looked just as the knight remembered him, still

strong and lithe with all the clarity of his wits behind his piercing black

eyes.

Growing old was a bittersweet blessing in time of war, and

the years had certainly passed, but he had never expected that something as

mundane as time could affect those of his father’s household.

Nestor chuckled at the wistfulness and perhaps even despair

in Daerwin’s eyes. “Come, come, lad. Things are not as bleak as they seem.

Not yet, at any rate. To that end,” he said with a vague gesture upward,

toward the high stone ceiling, toward the smaller audience chamber on the

second floor, “best we not keep your father waiting.”

Daerwin nodded and let Nestor lead him like a stranger

through the very halls where he had learned to walk.

Castle Damerien stood not a half-day’s ride from Brannagh,

but somehow, he usually found ways to avoid making the journey. Until his

father’s illness, neither he nor the duke had spent much time this far from the

front lines. While his father’s armies had slowed Kadak’s advances across the

south, Lord Daerwin and his forces had been far to the north destroying supply

lines and keeping the enemy contained. The duke had fallen ill at the first snows

of the Feast of Bilkar, and the duty to lead the lords of Syon and their

knights and vassals against the Usurper had fallen entirely to Daerwin, leaving

him with even less time or reason to come this far behind the lines.

So he had told himself, at any rate.

The truth was that since he had succeeded his uncle as

Sheriff of Brannagh, he had been back to Castle Damerien only once, nearly ten

years ago. He had come for his mother’s funeral. Apart from public matters,

the war and other affairs of state, the funeral had been the last time he and

his father had had time or privacy to speak of anything other than the war. And

such a strange conversation it had been…

Daerwin, I must see you at once. The time has come.

“Thick evening coming, aye?” Nestor offered, taking up a

fresh candelabrum to light their way once they passed the grand archway leading

toward the great hall. “The whole air’s a clot of steam, so it seems to me.”

“Aye,” answered the sheriff, grateful for the distraction.

“Damp and hot. Didian owes us a rain, and I expect a full storm by midday

tomorrow, an He fails to temper it. Could harm the crops. They’re young yet,

and they’re all that stand between us and another famine, come the Gathering.

But better rain than this heat.”

Nestor chuckled to himself.

“What, you think not?”

“Oh, far be it from me, my lord. What I know of farming’d

fit on the point of a pin,” murmured the servant. He stepped aside of habit to

let the nobleman enter the great hall ahead of him. “No, my thought it was that

tending your farmers suits you.” He glanced up at the young man’s back as he

passed. “A shame you’ve the war instead.”

“Indeed,” came Daerwin’s soft answer, but the conversation

was already forgotten. The young lord had stopped just inside the doorway, his

eyes wide.

Of all the myriad chambers and galleries at Castle Damerien,

this great hall had always been his favorite, a huge open space bound only by

intricate tapestries, murals and frescoes depicting scenes from Syon’s glorious

past. Ancient lances and swords had been mounted most respectfully under

banners of knights and noble houses. Some of the ancient houses were long dead

or forgotten. Others, like Windale and Tremondy, were still strong and well

respected. Daerwin had loved this room above all others as a boy, and his

young imagination had soared surrounded by the legends and relics of Syon’s

history. It was one thing to hear tired old lists of Borowain the

Peacekeeper’s achievements; it was quite another to touch the bloodstains on his

shield.

He found no comfort here now, though everything was just

where he remembered it. Thick dust choked the famous Damerien tapestries, and

the duke’s prized murals chipped and peeled with neglect. Between them, the

priceless weapons and armor lay rusting against the walls, too weary to stand

quite straight beneath their tilted banners. But it was more than just this

chamber. He had felt it at the fountain, even at the gates. The stones, the

mortar, the very walls of the castle seemed ready to fall in on him. Damerien

was crumbling. He looked once more at the white of Nestor’s hair and felt his

scalp crawl.

Please, he prayed, please let it not be so.

“Something, my lord?” Nestor’s gaze touched quickly on the

walls, the murals, the tapestries, but he continued on toward the stairway.

“No, no.” The duke’s son quickened his step to follow,

trying to stifle the horror that grew in his heart. When Nestor paused to look

back at him, Daerwin smiled weakly. “Lead on.”

“As you say, my lord.”

Some of the tapestries swelled and soughed in his wake,

shedding their dust like lazy soldiers snapping to attention. By the gods,

even as wilted as they were, they were glorious. He’d spent hours in this room

looking at the tiny details, wondering what the tiny stitched soldiers’

postures meant and what the legends scrawled in the bold strokes of ancient

Byrandian dialects said.

One tapestry depicted the end of the Battle of Berendor in

lavish scarlets and golds, where the forgotten gods and Their followers had surrendered

at the end of the Gods’ Rebellion. He’d understood even as a boy why the

forgotten gods had been portrayed without faces, but if he stared long enough,

he would see the shadows of noses and hints of eyes.

A fresco nearby, done in glinting blues and silvers, of all

his favorite, showed Galorin, the legendary sorcerer, and his bold coup at

Pyran that at a stroke had severed Syon’s ties to the continent and freed her

land and her people from the rule of Byrandia’s king. The Liberation was

perhaps the greatest moment in Syonese history, but he’d always wondered at the

hint of sadness in the sorcerer’s face.

Others showed the Bremo-Hadrian Wars and the earliest

battles of the present war, that which they’d taken to calling the Five Hundred

Years War in the hopes that it would end before it became the Six Hundred Years

War.

Reds, blues, silver and gold, they were, rich, living colors

of battle, of victory, and always at the center of these heroic battles was the

golden-eyed dragon, sigil of the Great Liberator and his descendents, the House

of Damerien. So much heroism, so much honor, all gathered in this hall.

The sheriff’s step faltered.

In a few days the sheriff would lead his knights and farmers

against Kadak’s legions again. Baron Tremondy’s forces in the north had

managed a small victory; not enough to force a retreat, but enough to frustrate

Kadak’s newest supply lines into the south. Unfortunately, the baron’s losses

had been terrible. Without immediate reinforcements from Brannagh, Tremondy

and his followers would fall, leaving an open sluice for Kadak right through

the Bremondine forests, past Brannagh’s flank to Castle Damerien herself.

No one—not Brannagh, not even Damerien himself—could say

what had unleashed Kadak and his demon armies upon Syon so long ago. Scraps of

prophecy held by the various temples had spoken of a war against a monstrous

beast, the harbinger of a new age, which everyone but the dimmest souls took to

mean Kadak. While they did not speak of the creature’s origins, they hinted

tantalizingly of his end, obscure, maddening hints which had driven Kadak to

unspeakable acts of genocide in an effort to forestall his death. Daerwin

wondered if a single man or woman of the Art remained alive on Syon after

Kadak’s vicious pogrom. Now, stripped of their mightiest allies against him,

the lords of Syon were forced to battle Kadak’s demonic legions themselves,

sword to ax, blood to blood.

This would be no tapestry battle. Even if Brannagh and

Tremondy together could manage to drive Kadak back into the Hodrache Range, a

feat in itself, they could not hope to weaken his hold on the coastal cities.

His presence, his terrible presence, was too firmly established there, giving

him a ready supply line into the south even if they could manage to cut off his

supply lines in the north. They simply would not have enough men left to

challenge him outright. The best they could expect would be to slow his

armies’ advance toward the duke’s castle and gain the Resistance some time.

Then they could plan a few new ways to gain a little more time, and, if they

were lucky, a little more after that.

Just as they had for five centuries.

No. They could not keep up as they had for much longer, and

even if no one else could see the signs of it, Daerwin could. This war was a

slow, unrelenting saraband of gain and loss, advance and retreat, and not

without its price. The combined armies of the Resistance now numbered but a

quarter what they had a century ago. A good part of the land stood untilled for

lack of hands to farm it, which would lead to starvation and more death.

Meanwhile, Kadak’s inexhaustible armies continued to chip away at them, battle

by battle. Before long, there would be no Resistance.

Then the duke would resort to more drastic measures.

Terrifying measures. But not yet, Daerwin told himself firmly, not just yet.

Please, not yet.

The time has come.

At last they reached the huge spiral stairway that led up to

the duke’s audience chamber, and gratefully, Daerwin turned his eyes away from

the banners, away from the shields and armor and weapons that slumped against

the walls, away from the tapestries, away from those terrible golden eyes.

Nestor climbed the stairs ahead of him, his crumpled back

silhouetted against the candelabrum he carried, but Daerwin could still somehow

feel the servant’s attention on him, as if the old man were waiting for him to

do something, say something.

“How is he?” the sheriff asked at last, struggling to keep

his voice calm.

“Well as can be expected,” answered the retainer. But he

paused at the top of the stairs and drew breath, choosing his words. “Best I

warn your Honor,” he began carefully, “His Grace is not in the best humor this

evening.” He glanced sideways at the duke’s son. “His gout is at him again.”

“Gout.” Daerwin frowned. Nestor, bless his heart, was

trying to prepare him for something, and against the duke’s express orders, no

doubt. But what it was, Daerwin could not see. Or would not.

“Aye, my lord, and all the rest, too. It’s his age, you

see...” The retainer shrugged, and his voice trailed away as he continued up

the stairway. “The years pass, yes, they do. A man can’t be bound to bully on

forever.”

His age. The sheriff’s hands trembled, and his heart

raced. He only wished he understood, or that he did not. He could not be

certain which. He stopped in the stairway and breathed deeply, trying to

regain his composure. In battle, he could keep an icy calm, but here, in his

father’s house…

The time has come.

A sick feeling rose in his gut, but he fought it down,

taking himself breath by breath up the staircase. Soon enough, he told

himself, taking hope from the cheerful smells of the feast being prepared in

the kitchens below. Soon enough, he would know his father’s mind. Until then,

he could do nothing.

When Daerwin caught up, Nestor fell into step beside him.

“Been expecting you since midday, he has.” His voice dropped to a whisper as

they turned the corner toward the audience chamber. “A bit impatiently, I

might add.”

“Impatient, bah,” came a crackling voice from the slightly

open door ahead. “I am far, far too old to grow impatient at a few hours’ wait

for my son. You needn’t warn him against me, Nestor.”

The retainer was pushing the heavy door open as the duke

spoke. “Very good, your Grace,” he said with a resigned bow. Then, avoiding

Daerwin’s gaze, he stood aside to let the sheriff enter the chamber, announcing

the young man as he passed. “Presenting Lord Daerwin, the Honorable Sheriff of

Brannagh.”

“Shire-Reeve,” the bundle of thick Bremondine blankets on

the throne snarled. “My son is the Shire-Reeve of Brannagh! Even the language

has no integrity anymore.”

Without waiting to be dismissed, Nestor withdrew, pulling

the doors closed behind him.

Just as Daerwin had feared, the audience chamber felt as

dead to him as the great hall below. Bare stone floor gleamed for miles, so it

seemed, in every direction, an illusion broken only by the modest throne at the

far corner, with a plain wooden chair beside it.