Read Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures Online

Authors: Robert E. Howard

Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures (35 page)

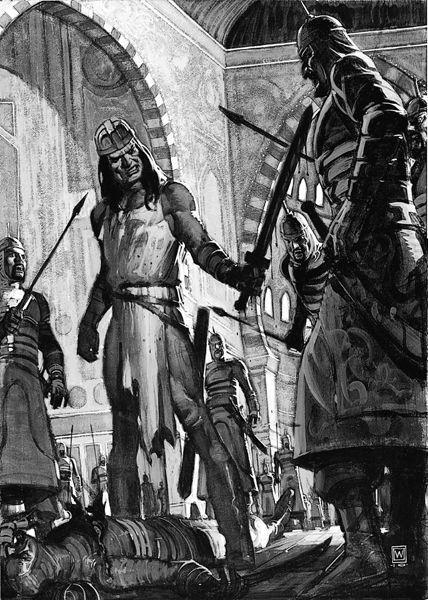

Saladin merely smiled in a weary way. Half a century of intrigue and warring rested heavily on his shoulders. His brown eyes, strangely mild for so great a lord, rested on the silent Frankish giant who still stood with his mail-clad foot on what had been the chief Kosru Malik.

“And what is this?” asked the Sultan.

Nureddin scowled: “A Nazarene outlaw has stolen into my keep and assassinated my comrade, the Seljuk. I beg your leave to dispose of him. I will give you his skull, set in silver – ”

A gesture stopped him. Saladin stepped past his men and confronted the dark, brooding warrior.

“I thought I had recognized those shoulders and that dark face,” said the Sultan with a smile. “So you have turned your face east again, Lord Cormac?”

“Enough!” The deep voice of the Norman-Irish giant filled the chamber. “You have me in your trap; my life is forfeit. Waste not your time in taunts; send your jackals against me and make an end of it. I swear by my clan, many of them shall bite the dust before I die, and the dead will be more than the living!”

Nureddin’s tall frame shook with passion; he gripped his hilt until the knuckles showed white. “Is this to be borne, my Lord?” he exclaimed fiercely. “Shall this Nazarene dog fling dirt into our faces – ”

Saladin shook his head slowly, smiling as if at some secret jest: “It may be his is no idle boast. At Acre, at Azotus, at Joppa I have seen the skull on his shield glitter like a star of death in the mist, and the Faithful fall before his sword like garnered grain.”

The great Kurd turned his head, leisurely surveying the ranks of silent warriors and the bewildered chieftains who avoided his level gaze.

“A notable concourse of chiefs, for these times of truce,” he murmured, half to himself. “Would you ride forth in the night with all these warriors to fight genii in the desert, or to honor some ghostly sultan, Nureddin? Nay, nay, Nureddin, thou hast tasted the cup of ambition, meseemeth – and thy life is forfeit!”

The unexpectedness of the accusation staggered Nureddin, and while he groped for reply, Saladin followed it up: “It comes to me that you have plotted against me – aye, that it was your purpose to seduce various Moslem and Frankish lords from their allegiances, and set up a kingdom of your own. And for that reason you broke the truce and murdered a good knight, albeit a Caphar, and burned his castle. I have spies, Nureddin.”

The tall Arab glanced quickly about, as if ready to dispute the question with Saladin himself. But when he noted the number of the Kurd’s warriors, and saw his own fierce ruffians shrinking away from him, awed, a smile of bitter contempt crossed his hawk-like features, and sheathing his blade, he folded his arms.

“God gives,” he said simply, with the fatalism of the Orient.

Saladin nodded in appreciation, but motioned back a chief who stepped forward to bind the sheik. “Here is one,” said the Sultan, “to whom you owe a greater debt than to me, Nureddin. I have heard Cormac FitzGeoffrey was brother-at-arms to the Sieur Gerard. You owe many debts of blood, oh Nureddin; pay one, therefore, by facing the lord Cormac with the sword.”

The Arab’s eyes gleamed suddenly. “And if I slay him – shall I go free?”

“Who am I to judge?” asked Saladin. “It shall be as Allah wills it. But if you fight the Frank you will die, Nureddin, even though you slay him; he comes of a breed that slays even in their death-throes. Yet it is better to die by the sword than by the cord, Nureddin.”

The sheik’s answer was to draw his ivory-hilted saber. Blue sparks flickered in Cormac’s eyes and he rumbled deeply like a wounded lion. He hated Saladin as he hated all his race, with the savage and relentless hatred of the Norman-Celt. He had ascribed the Kurd’s courtesy to King Richard and the Crusaders to Oriental subtlety, refusing to believe that there could be ought but trickery and craftiness in a Saracen’s mind. Now he saw in the Sultan’s suggestion but the scheming of a crafty trickster to match two of his foes against each other, and a feline-like gloating over his victims. Cormac grinned without mirth. He asked no more from life than to have his enemy at sword-points. But he felt no gratitude toward Saladin, only a smoldering hate.

The Sultan and the warriors gave back, leaving the rivals a clear space in the center of the great room. Nureddin came forward swiftly, having donned a plain round steel cap with a mail drop that fell about his shoulders.

“Death to you, Nazarene!” he yelled, and sprang in with the pantherish leap and headlong recklessness of an Arab’s attack. Cormac had no shield. He parried the hacking saber with upflung blade, and slashed back. Nureddin caught the heavy blade on his round buckler, which he turned slightly slantwise at the instant of impact, so that the stroke glanced off. He returned the blow with a thrust that rasped against Cormac’s coif, and leaped a spear’s length backward to avoid the whistling sweep of the Norse sword.

Again he leaped in, slashing, and Cormac caught the saber on his left forearm. Mail links parted beneath the keen edge and blood spattered, but almost simultaneously the Norse sword crashed under the Arab’s arm, bones cracked and Nureddin was flung his full length to the floor. Warriors gasped as they realized the full power of the Irishman’s tigerish strokes.

Nureddin’s rise from the floor was so quick that he almost seemed to rebound from his fall. To the onlookers it seemed that he was not hurt, but the Arab knew. His mail had held; the sword edge had not gashed his flesh, but the impact of that terrible blow had snapped a rib like a rotten twig, and the realization that he could not long avoid the Frank’s rushes filled him with a wild beast determination to take his foe with him to Eternity.

Cormac was looming over Nureddin, sword high, but the Arab, nerving himself to a dynamic burst of superhuman quickness, sprang up as a cobra leaps from its coil, and struck with desperate power. Full on Cormac’s bent head the whistling saber clashed, and the Frank staggered as the keen edge bit through steel cap and coif links into his scalp. Blood jetted down his face, but he braced his feet and struck back with all the power of arm and shoulders behind the sword. Again Nureddin’s buckler blocked the stroke, but this time the Arab had no time to turn the shield, and the heavy blade struck squarely. Nureddin went to his knees beneath the stroke, bearded face twisted in agony. With tenacious courage he reeled up again, shaking the shattered buckler from his numbed and broken arm, but even as he lifted the saber, the Norse sword crashed down, cleaving the Moslem helmet and splitting the skull to the teeth.

Cormac set a foot on his fallen foe and wrenched free his gory sword. His fierce eyes met the whimsical gaze of Saladin.

“Well, Saracen,” said the Irish warrior challengingly, “I have killed your rebel for you.”

“And your enemy,” reminded Saladin.

“Aye,” Cormac grinned bleakly and ferociously. “I thank you – though well I know it was no love of me or mine that prompted you to send the Arab against me. Well – make an end, Saracen.”

“Why do you hate me, Lord Cormac?” asked the Sultan curiously.

Cormac snarled. “Why do I hate any of my foes? You are no more and no less than any other robber chief, to me. You tricked Richard and the rest with courtly words and fine deeds, but you never deceived me, who well knew you sought to win by deceit where you could not gain by force of arms.”

Saladin shook his head, murmuring to himself. Cormac glared at him, tensing himself for a sudden leap that would carry the Kurd with him into the Dark. The Norman-Gael was a product of his age and his country; among the warring chiefs of blood-drenched Ireland, mercy was unknown and chivalry an outworn and forgotten myth. Kindness to a foe was a mark of weakness; courtesy to an enemy a form of craft, a preparation for treachery; to such teachings had Cormac grown up, in a land where a man took every advantage, gave no quarter and fought like a blood-mad devil if he expected to survive.

Now at a gesture from Saladin, those crowding the door gave back.

“Your way is open, Lord Cormac.”

The Gael glared, his eyes narrowing to slits: “What game is this?” he growled. “Shall I turn my back to your blades? Out on it!”

“All swords are in their sheaths,” answered the Kurd. “None shall harm you.”

Cormac’s lion-like head swung from side to side as he glared at the Moslems.

“You honestly mean I am to go free, after breaking the truce and slaying your jackals?”

“The truce was already broken,” answered Saladin. “I find in you no fault. You have repaid blood for blood, and kept your faith to the dead. You are rough and savage, but I would fain have men like you in mine own train. There is a fierce loyalty in you, and for this I honor you.”

Cormac sheathed his sword ungraciously. A grudging admiration for this weary-faced Moslem was born in him and it angered him. Dimly he realized at last that this attitude of fairness, justice and kindliness, even to foes, was not a crafty pose of Saladin’s, not a manner of guile, but a natural nobility of the Kurd’s nature. He saw suddenly embodied in the Sultan, the ideals of chivalry and high honor so much talked of – and so little practiced – by the Frankish knights. Blondel had been right then, and Sieur Gerard, when they argued with Cormac that high-minded chivalry was no mere romantic dream of an outworn age, but had existed, and still existed and lived in the hearts of certain men. But Cormac was born and bred in a savage land where men lived the desperate existence of the wolves whose hides covered their nakedness. He suddenly realized his own innate barbarism and was ashamed. He shrugged his lion’s shoulders.

“I have misjudged you, Moslem,” he growled. “There is fairness in you.”

“I thank you, Lord Cormac,” smiled Saladin. “Your road to the west is clear.”

And the Moslem warriors courteously salaamed as Cormac FitzGeoffrey strode from the royal presence of the slender noble who was Protector of the Caliphs, Lion of Islam, Sultan of Sultans.

The Blood of Belshazzar

It shone on the breast of the Persian king,

It lighted Iskander’s road;

It blazed where the spears were splintering,

A lure and a maddening goad.

And down through the crimson, changing years

It draws men, soul and brain;

They drown their lives in blood and tears,

And they break their hearts in vain.

Oh, it flames with the blood of strong men’s hearts

Whose bodies are clay again.

– The Song of the Red Stone

I

Once it was called Eski-Hissar, the Old Castle, for it was very ancient even when the first Seljuks swept out of the east, and not even the Arabs, who rebuilt that crumbling pile in the days of Abu Bekr, knew what hands reared those massive bastions among the frowning foothills of the Taurus. Now, since the old keep had become a bandit’s hold, men called it Bab-el-Shaitan, the Gate of the Devil, and with good reason.

That night there was feasting in the great hall. Heavy tables loaded with wine pitchers and jugs, and huge platters of food, stood flanked by crude benches for such as ate in that manner, while on the floor large cushions received the reclining forms of others. Trembling slaves hastened about, filling goblets from wineskins and bearing great joints of roasted meat and loaves of bread.

Here luxury and nakedness met, the riches of degenerate civilizations and the stark savagery of utter barbarism. Men clad in stenching sheepskins lolled on silken cushions, exquisitely brocaded, and guzzled from solid golden goblets, fragile as the stem of a desert flower. They wiped their bearded lips and hairy hands on velvet tapestries worthy of a shah’s palace.

All the races of western Asia met here. Here were slim, lethal Persians, dangerous-eyed Turks in mail shirts, lean Arabs, tall ragged Kurds, Lurs and Armenians in sweaty sheepskins, fiercely mustached Circassians, even a few Georgians, with hawk-faces and devilish tempers.

Among them was one who stood out boldly from all the rest. He sat at a table drinking wine from a huge goblet, and the eyes of the others strayed to him continually. Among these tall sons of the desert and mountains his height did not seem particularly great, though it was above six feet. But the breadth and thickness of him were gigantic. His shoulders were broader, his limbs more massive than any other warrior there.