Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures (51 page)

Read Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures Online

Authors: Robert E. Howard

The sun was sinking toward the horizon when, foaming with rage that for once drowned his gargantuan laughter, he launched an irresistible charge upon the dying handful that tore them apart and scattered their corpses over the plain.

Here and there single knights or weary groups, like the drift of a storm, were ridden down by the chanting riders who swarmed the plain.

Cahal O’Donnel walked dazedly among the dead, the notched and crimsoned sword trailing in his weary hand. His helmet was gone, his arms and legs gashed, and from a deep wound beneath his hauberk, blood trickled sluggishly.

And suddenly his head jerked up.

“Cahal! Cahal!”

He drew an uncertain hand across his eyes. Surely the delirium of battle was upon him. But again the voice rose, in agony.

“Cahal!”

He was close to a boulder-strewn knoll where the dead lay thick. Among them lay Wulfgar the Dane, his unshaven lip a-snarl, his red beard tilted truculently, even in death. His mighty hand still gripped his ax, notched and clotted red, and a gory heap of corpses beneath him gave mute evidence of his berserk fury.

“Cahal!”

The Gael dropped to his knees beside the slender figure of the Masked Knight. He lifted off the helmet – to reveal a wealth of unruly black tresses – gray eyes luminous and deep. A choked cry escaped him.

“Saints of God! Elinor! I dream – this is madness – ”

The slender mailed arms groped about his neck. The eyes misted with growing blindness. Through the pliant links of the hauberk blood seeped steadily.

“You are not mad, Red Cahal,” she whispered. “You do not dream. I am come to you at last – though I find you but in death. I did you a deathly wrong – and only when you were gone from me forever did I know I loved you. Oh, Cahal, we were born under a blind unquiet star – both seeking goals of fire and mist. I loved you – and knew it not until I lost you. You were gone – I knew not where.

“The Lady Elinor de Courcey died then, and in her place was born the Masked Knight. I took the Cross in penance. Only one faithful servitor knew my secret – and rode with me – to the ends of the earth – ”

“Aye,” muttered Cahal, “I remember him now – even in death he was faithful.”

“When I met you among the hills below Jerusalem,” she whispered faintly, “my heart tore at its strings to burst from my bosom and fall in the dust at your feet. But I dared not reveal myself to you. Ah, Cahal, I have done bitter penance! I have died for the Cross this day, like a knight. But I ask not forgiveness of God. Let Him do with me as He will – but oh, it is forgiveness of you I crave, and dare not ask!”

“I freely forgive you,” said Cahal heavily. “Fret no more about it, girl; it was but a little wrong, after all. Faith, all things and the deeds and dreams of men are fleeting and unstable as moon-mist, even the world which has here ended.”

“Then kiss me,” she gasped, fighting hard against the onrushing darkness.

Cahal passed his arm under her shoulders, lifting her to his blackened lips. With a convulsive effort she stiffened half erect in his arms, her eyes blazing with a strange light.

“The sun sets and the world ends!” she cried. “But I see a crown of red gold on your head, Red Cahal, and I shall sit beside you on a throne of glory! Hail, Cahal, chief of Uland; hail, Cahal Ruadh,

ard-ri na Eireann

– ”

She sank back, blood starting from her lips. Cahal eased her to the earth and rose like a man in a dream. He turned toward the low slope and staggered with a passing wave of dizziness. The sun was sinking toward the desert’s rim. To his eyes the whole plain seemed veiled in a mist of blood through which vague fantasmal figures moved in ghostly pageantry. A chaotic clamor rose like the acclaim to a king, and it seemed to him that all the shouts merged into one thunderous roar:

“Hail, Cahal Ruadh, ard-ri na Eireann!”

He shook the mists from his brain and laughed. He strode down the slope, and a group of hawk-like riders swept down upon him with a swift rattle of hoofs. A bow twanged and an iron arrowhead smashed through his mail. With a laugh he tore it out and blood flooded his hauberk. A lance thrust at his throat and he caught the shaft in his left hand, lunging upward. The gray sword’s point rent through the rider’s mail, and his death-scream was still echoing when Cahal stepped aside from the slash of a scimitar and hacked off the hand that wielded it. A spear-point bent on the links of his mail and the lean gray sword leaped like a serpent-stroke, splitting helmet and head, spilling the rider from the saddle.

Cahal dropped his point to the earth and stood with bare head thrown back, as a gleaming clump of horsemen swept by. The foremost reined his white horse back on its haunches with a shout of laughter. And so the victor faced the vanquished. Behind Cahal the sun was setting in a sea of blood, and his hair, floating in the rising breeze, caught the last glints of the sun, so that it seemed to Baibars the Gael wore a misty crown of red gold.

“Well,

malik

,” laughed the Tatar, “they who oppose the destiny of Baibars lie under my horses’ hoofs, and over them I ride up the gleaming stair of empire!”

Cahal laughed and blood started from his lips. With a lion-like gesture he threw up his head, flinging high his sword in kingly salute.

“Lord of the East!” his voice rang like a trumpet-call, “welcome to the fellowship of kings! To the glory and the witch-fire, the gold and the moon-mist, the splendor and the death! Baibars, a king hails thee!”

And he leaped and struck as a tiger leaps. Not Baibars’ stallion that screamed and reared, not his trained swordsmen, not his own quickness could have saved the memluk then. Death alone saved him – death that took the Gael in the midst of his leap. Red Cahal died in midair and it was a corpse that crashed against Baibars’ saddle – a falling sword in a dead hand that, the momentum of the blow completing its arc, scarred Baibar’s forehead and split his eyeball.

His warriors shouted and reined forward. Baibars slumped in the saddle, sick with agony, blood gushing from between the fingers that gripped his wound. As his chiefs cried out and sought to aid him, he lifted his head and saw, with his single, pain-dimmed eye, Red Cahal lying dead at his horse’s feet. A smile was on the Gael’s lips, and the gray sword lay in shards beside him, shattered, by some freak of chance, on the stones as it fell beside the wielder.

“A hakim, in the name of Allah,” groaned Baibars. “I am a dead man.”

“Nay, you are not dead, my lord,” said one of his memluk chiefs. “It is the wound from the dead man’s sword and it is grievous enough, but bethink you: here has the host of the Franks ceased to be. The barons are all taken or slain and the Cross of the patriarch has fallen. Such of the Kharesmians as live are ready to serve you as their new lord – since Kizil Malik slew their khan. The Arabs have fled and Damascus lies helpless before you – and Jerusalem is ours! You will yet be sultan of Egypt.”

“I have conquered,” answered Baibars, shaken for the first time in his wild life, “but I am half-blind – and of what avail to slay men of that breed? They will come again and again and again, riding to death like a feast because of the restlessness of their souls, through all the centuries. What though we prevail this little Now? They are a race unconquerable, and at last, in a year or a thousand years, they will trample Islam under their feet and ride again through the streets of Jerusalem.”

And over the red field of battle night fell shuddering.

The Skull in the Clouds

The Black Prince scowled above his lance, and wrath in his hot eyes lay,

“I would that you rode with the spears of France and not at my side today.

A man may parry an open blow, but I know not where to fend;

I would that you were an open foe, instead of a sworn friend.

“You came to me in an hour of need, and your heart I thought I saw;

But you are one of a rebel breed that knows not king or law.

You – with your ever smiling face and a black heart under your mail –

With the haughty strain of the Norman race and the wild, black blood of the Gael.

“Thrice in a night fight’s close-locked gloom my shield by merest chance

Has turned a sword that thrust like doom – I wot ’twas not of France!

And in a dust-cloud, blind and red, as we charged the Provence line

An unseen axe struck Fitzjames dead, who gave his life for mine.

“Had I proofs, your head should fall this day or ever I rode to strife.

Are you but a wolf to rend and slay, with naught to guide your life?

No gleam of love in a lady’s eyes, no honor or faith or fame?”

I raised my face to the brooding skies and laughed like a roaring flame.

“I followed the sign of the Geraldine from Meath to the western sea

Till a careless word that I scarcely heard bred hate in the heart of me.

Then I lent my sword to the Irish chiefs, for half of my blood is Gael,

And we cut like a sickle through the sheafs as we harried the lines of the Pale.

“But Dermod O’Connor wild with wine, called me a dog at heel,

And I cleft his bosom to the spine and fled to the black O’Neill.

We harried the chieftains of the south; we shattered the Norman bows.

We wasted the land from Cork to Louth; we trampled our fallen foes.

“But Conn O’Neill put on me a slight before the Gaelic lords,

And I betrayed him in the night to the red O’Donnell swords.

I am no thrall to any man, no vassal to any king.

I owe no vow to any clan, nor faith to any thing.

“Traitor – but not for fear or gold, but the fire in my own dark brain;

For the coins I loot from the broken hold I throw to the winds again.

And I am true to myself alone, through pride and the traitor’s part.

I would give my life to shield your throne, or rip from your breast the heart

“For a look or a word, scarce thought or heard. I follow a fading fire,

Past bead and bell and the hangman’s cell, like a harp-call of desire.

I may not see the road I ride for the witch-fire lamps that gleam;

But phantoms glide at my bridle-side, and I follow a nameless Dream.”

The Black Prince shuddered and shook his head, then crossed himself amain:

“Go, in God’s name, and never,” he said, “ride in my sight again.”

The starlight silvered my bridle-rein; the moonlight burned my lance

As I rode back from the wars again through the pleasant hills of France,

As I rode to tell Lord Amory of the dark Fitzgerald line

If the Black Prince died, it needs must be by another hand than mine.

A Thousand Years Ago

I was chief of the Chatagai

A thousand years ago;

Turan’s souls and her swords were high;

Arrows flew as snow might fly,

We shook the desert and broke the sky

When I was a chief of the Chatagai

A thousand years ago.

When I was a chief of the Chatagai,

A thousand years ago,

I bared my sword, I loosed the rein,

I shattered the shahs on Iran’s plain,

I smote on the walls of Rhoum in vain,

When I was chief of the Chatagai

A thousand years ago.

I was a chief of the Chatagai,

A thousand years ago,

And still I dream of the flying strife,

Of the desert dawns and the unreined life

When I took the wars of the world to wife –

When I was a chief of the Chatagai

A thousand years ago.

Lord of Samarcand

The roar of battle had died away; the sun hung like a ball of crimson gold on the western hills. Across the trampled field of battle no squadrons thundered, no war-cry reverberated. Only the shrieks of the wounded and the moans of the dying rose to the circling vultures whose black wings swept closer and closer until they brushed the pallid faces in their flight.

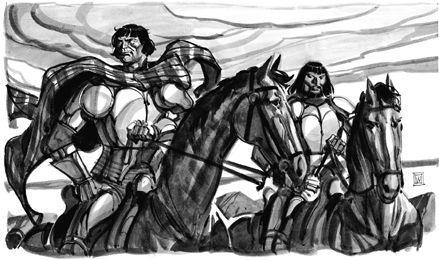

On his rangy stallion, in a hillside thicket, Ak Boga the Tatar watched, as he had watched since dawn, when the mailed hosts of the Franks, with their forest of lances and flaming pennons, had moved out on the plains of Nicopolis to meet the grim hordes of Bayazid.

Ak Boga, watching their battle array, had chk-chk’d his teeth in surprize and disapproval as he saw the glittering squadrons of mounted knights draw out in front of the compact masses of stalwart infantry, and lead the advance. They were the flower of Europe – cavaliers of Austria, Germany, France and Italy; but Ak Boga shook his head.