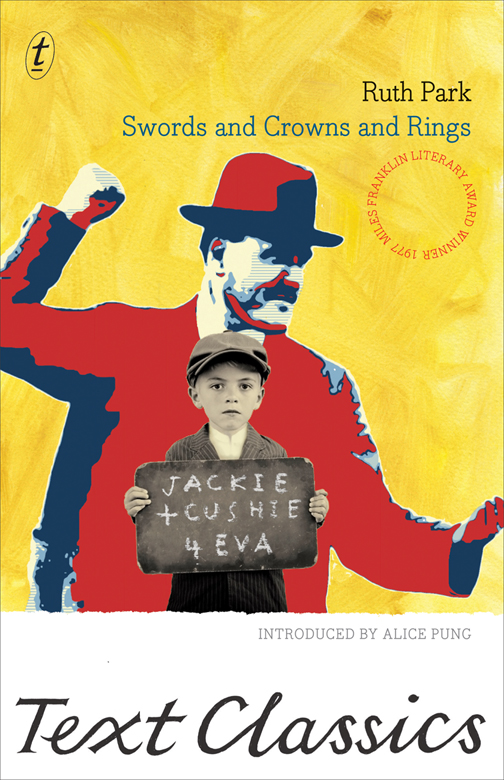

Swords and Crowns and Rings

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

RUTH PARK

was born in Auckland, New Zealand in 1917. After moving to Australia in 1942 she married the fellow journalist and author D'Arcy Niland. They travelled the outback, then settled in Sydney's Surry Hills to write. Park came to fame in 1946, when her novel

The Harp in the South

won the inaugural

Sydney Morning Herald

literary competition. The book was published in 1948 and translated into thirty-seven languages; the following year the equally popular sequel,

Poor Man's Orange

, appeared. Again, Park had captured the mood of Depression-era Australia.

After Niland died, in 1967, Park visited London before moving to Norfolk Island, where she lived for seven years before returning to Sydney.

Equally adept at writing for children, she created the Muddleheaded Wombat radio series in the 1950s, followed by fifteen Wombat books in the 1960s and '70s. The most famous of her other books for young readers,

Playing Beatie Bow

, was published in 1980 after

Swords and Crowns and Rings

, a return to writing for adults, had won the 1977 Miles Franklin Award.

A Fence Around the Cuckoo

(1992), her first volume of autobiography, was the

Age

Book of the Year.

In 1994 Park received an honorary D.Litt from the University of New South Wales. One of Australia's most loved authors, she died in 2010, having published more than fifty books.

ALICE PUNG

is the author of the bestselling memoir

Unpolished Gem

and

Her Father's Daughter

, and the editor of

Growing Up Asian in Australia

.

ALSO BY RUTH PARK

Novels

The Harp in the South

Poor Man's Orange

The Witch's Thorn

A Power of Roses

Serpent's Delight

Pink Flannel

One-a-Pecker, Two-a-Pecker

Missus

Â

Non-Fiction

The Drums Go Bang

(with D'Arcy Niland)

The Companion Guide to Sydney

The Sydney We Love

The Tasmania We Love

A Fence Around the Cuckoo

Fishing in the Styx

Home Before Dark

(with Rafe Champion)

Ruth Park's Sydney

Â

Thirty-eight books for children

Â

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

Copyright © Kemalde Pty Ltd 1977

Introduction copyright © Alice Pung 2012

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published by Thomas Nelson Australia Pty Ltd 1977

This edition published by The Text Publishing Company 2012

Cover design by WH Chong

Page design by Text

Typeset by Midland Typesetters

Printed in Australia by Griffin Press, an Accredited ISO AS/NZS 14001:2004

Environmental Management System printer

Primary print ISBN: 9781922079510

Ebook ISBN: 9781921961793

eBook production by

Midland Typesetters

, Australia

Â

CONTENTS

Â

Against Calamitous Odds

by Alice Pung

VII

Â

1

Â

I first came across the work of Ruth Park in primary school. There was something viscerally real about the olden-day world of

Playing Beatie Bow

. I couldn't properly understand itâbut, looking back now, I realise that the power of âSydney's Dickens' lay in her ability to write about love, sex and death with an innocence unmarred by adult stigmas.

Swords and Crowns and Rings

was published in 1977, not long before

Playing Beatie Bow

, and it won the Miles Franklin Award. The saga takes place in the first three decades of the twentieth century, and like Park's much-loved novels of the late 1940s,

Harp in the South

and

Poor Man's Orange

, it's about the stoic poor. Yet there is a shift from the deep-rooted sense of community in her earlier books, set in the slums of inner-city Sydney, to Jackie Hanna and Cushie Moy's quest for individual self-realisation. While Park does not flinch from portraying stark privation, this novel marks the beginning of a new, transcendental consciousness in her characters.

Propelled by their Tolkien-like search for a kingdom of dwarves who make âswords and crowns and rings', Jackie and Cushie share an enchanted childhood. They are completely unselfconscious, and so are completeââthey had always been two sides of the same coin: she, in her physical perfection and defencelessness, like a beautiful gentle bird, he so small and grotesque, and yet hardy, full of purpose.'

When their unified sense of self is shattered by forced separation, they endure almost a decade apart from each other. Like the Buddhist symbol of the lotus whose roots grip the bottom of the muddy swamp but whose head rises cleanly above the water, though, Park's protagonists accept life's vicissitudes. They suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, but their most profound journey is to maintain their integrity against calamitous odds.

This allegorical journey of emerging adulthood came out of a period of great social and political change. Influenced by the civil rights movement in the United States, Australia saw the passage of the first equal-opportunity legislation in 1975. Diversity was no longer quashed by assimilationist policiesâit was becoming the nation's new narrative. The character of Jackie could be nuanced and human without needing to represent difference.

Park had by this time abandoned the Catholic faith of her youth and become interested in Zen Buddhism. She had also seen some of the world beyond the antipodes since the publication of her last major novel, in 1957.

Swords and Crowns and Rings

was her return to publishing for adults after spending the previous two decades predominantly writing children's books and radio plays. When Park sat down to write about Jackie and Cushie, she was no longer dealing with fixed absolutes but with fluid, more radical identities.

The prostitutes and derelicts, the homeless men and indigent immigrant farming women who epitomise Park's gritty realism still populate this book; but there is also a pair of affectionate quarrelsome women lovers, Claudie and Iris, and a victim of violence and incest, who becomes one of the strongest figures in the novel. Most strikingly, the protagonist, whose presence would cause discomfort and antagonism in a time of ignorance and poverty, is always rendered with dignity. Jackie is not a quirk of a man but manhood at its finest. His identity is forged through unemployment, physical violence and the Depression.

The gentle irony in this expansive novel is that garrulousness is seen as a flaw, and the deepest characters are those who do not speak much: the Nun, Lufa, the magisterial ailing German grandfather. These are solitary men whose lives run slowly, on self-sustaining cogs, and their actions render them substantial. âProbably I am a writer because I had a singular childhood,' Park once wrote. âMy first seven years I spent all alone in the forest, like a possum or bear cub.' She did not grow up in a household full of books, instead learning to be an astute eavesdropper and an observer of the human condition. The characters that fascinated her most were those with eccentricities, their faces lined with the calligraphic marks of experience.

Park set much of

Swords and Crowns and Rings

in rural Australia, a reticent place where folk have no need to vocalise every thought that passes through their minds. âI saw a little of this vast, magnificent land, and was captured forever by its noble indifference to humankind,' she observed. âI felt that one day this continent would give a shrug and shake all the humans off into the sea. But it would still be its own self. That's what I call identity.'

The characters' external surrounds mirror their internal universes: Jackie's strength and resilience are as immutable as the inviolate land from which he comes, while Cushie is as soft and beautiful as her artificial environment, where the family wealth perches on a precipice, liable at any time to fall. Cushie, ostensibly so lamblike, is essential to Jackie's developing sense of manhood. Unsure about the parameters of her existence, uncertain where the world ends and she begins, Cushie is constantly bumping up against sharp corners. Jackie is not so troubled: he has a role model of noble, good-humoured masculinity, the Nun; and the love of a strong woman, his mother. Cushie's glacial mother, Isobel, and her inwardly cowering father impose silence in the houseâsilence born not of dignity but fear. A young woman of infinite faith and utter dependency, Cushie has femininity imposed upon her; she is trapped by it, despite her attempts to gain control.

Maida, on the other hand, is Jelka Sepic in John Steinbeck's story âThe Murder' rendered three-dimensional, with agency and a voice. Stronger and more courageous than Cushie, she suffers vicious cruelty but remains tender and kind. She did not grow up in refinement, yet maintains a sense of quiet self-respect, as Jackie notices: âhe became aware that Maida had a little bag of herbs around her neck on a string, and he was touched at this fastidiousness in one whose life was so isolated and austere.' Maida is egoless, never having had the chance to choose, to develop her own identity. A cornered creature on the cruel family farm, she can only make small gestures of kindness without considering the consequences.