Tailor of Inverness, The (10 page)

Read Tailor of Inverness, The Online

Authors: Matthew Zajac

That’s the way I’m, more or less, carried on. The contracts, army contracts came in. Well I took that contract. Queen’s Own Highlander were there at Fort George that time. They moved out, the Fort George was finished and I immediately got a proposal from RAF Kinloss, the contract with Kinloss, so I took that you see? I had that for about 15 years. I always

put the prices up every two years. Up, up, up, I say, well if they not want to to to, they no want it that, I’m not er, you know. But oh, I always got it, you know? Till the last time and Joe Setts was quartermaster and I say well you want to renew again? He know my age, pension time, you know? He say maybe you want to retire? Well, I probably will retire. Well ok, just retire he says and we’ll try to get somebody else. So they did, right enough, but that somebody else wasn’t any good and they asked me few times could I take it back, you see? I say och, I no going to start again, you know?

I got a note, the letter from them, just about a 2 or 3 months ago. Would you renew the contract in February? But och, I didn’t bother with it, no…so…

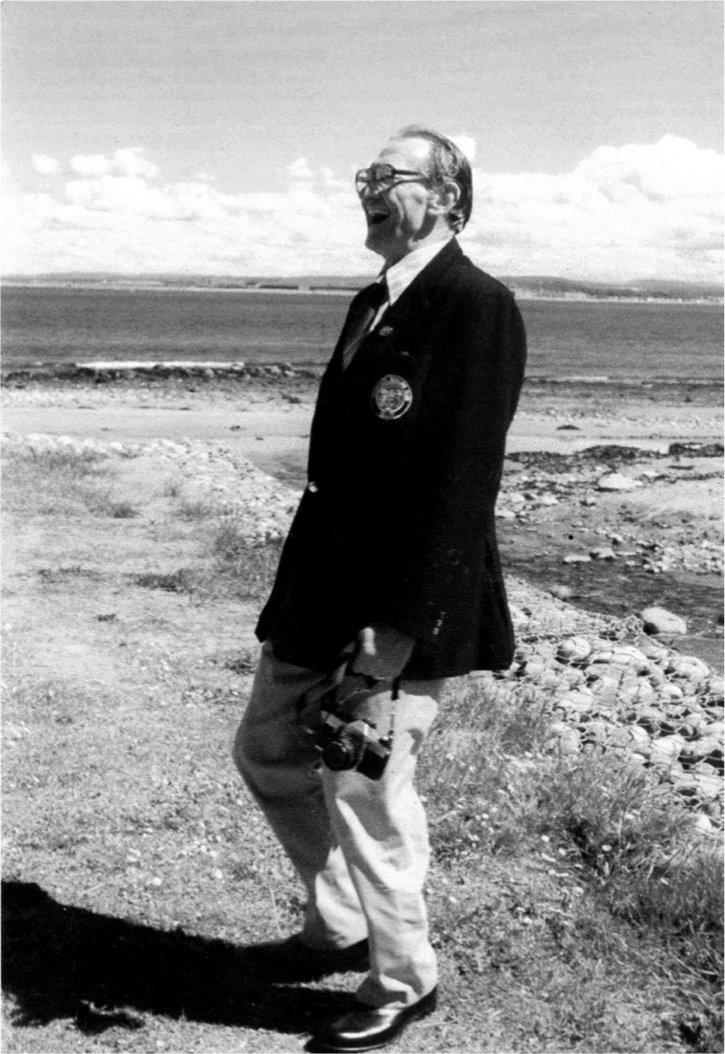

Mateusz, Easter Ross c.1988

I have the happy life in Inverness. Quiet life. Raised the family. Go to British Legion. Go to bingo. Good friends, aye. Every year in November to Invergordon to Polish War Memorial for the Service of Remembrance. So that’s it. That’s it. Aye.

I went to university in Bristol, over 800 kilometres and a world away from my childhood in Inverness. I was naïve and eager to adapt and learn. My parents had invested a great deal of energy and hope in our education, but my decision to choose the theatre caused them some concern. This was assuaged by my agreement, and my desire, to attend university rather than a drama school. I knew I was entering a profession full of uncertainty, with no security and a great deal of competition. I was grateful to my parents for their forbearance. They may have been sceptical and worried about my future prospects, but they recognised that I had some talent and they respected my choice.

In the 1980s there were terrible periods of depressing

unemployment

, but I was relatively lucky, and I also worked a lot, creating new plays, acting in rep theatres around the UK, getting my first jobs in film and TV. Poland, and my

connection

with it, receded. I was preoccupied and, most importantly, I lacked the language. Occasionally it would gnaw away at me, but I didn’t do anything about it. Most of the time, I simply forgot about it all. I did keep abreast of political

developments

, though, through newspapers and TV.

Like most people at the time, I watched the Gdansk dockers’ strike of 1980 and the extraordinary rise of

Solidarnosc

(Solidarity), which became a massive oppositional movement in Poland with over 9 million members within months of its establishment. General Jaruzelski’s government cracked down on

Solidarnosc

on December 13

th

1981 by imposing a state of martial law throughout the country. Around 100 people were killed and thousands were interned.

Solidarnosc

, along with many other independent organisations, was outlawed.

In the spring of 1983, I was working with Bush Telegraph Theatre Company in Bristol. We devised a powerful

theatre-in

-education project set in Gdansk on the day martial law was declared. It was a site-specific production. We gained access to several buildings in the old docks of central Bristol, which were just beginning to be regenerated at the time. At the start of each performance, a busload of 12-13 year-olds arrived outside the newly opened Watershed Arts Centre and I’d jump on with a camera operator, posing as a journalist. I made a quick report to camera, explaining that we were on our way to Gdansk where we’d find out what life was really like in the Polish People’s Republic. The bus drove into the dock area and we turned a corner into a street flanked by warehouses. We’d set up a road barrier there, the Polish border, where a soldier made a cursory search of the bus as the port director of Gdansk introduced himself to the children and explained that he was about to give them a guided tour of the port. During the next half hour or so, the children’s ‘official’ tour was interrupted by Solidarity activists distributing leaflets and arguing with the port director. This culminated in the children working with the activists in a warehouse, printing leaflets and making banners.

During this sequence, a loudspeaker announced the

declaration

of martial law and the banning of public gatherings. This was followed a few minutes later by a raid on the warehouse

by the ZOMO, the notorious Polish paramilitary police. Before the children were hurried out, they witnessed a riot policeman beating one of the activists. They returned to the bus where two activists were hiding, trying to escape across the border. They were discovered by soldiers and dragged off, despite the best efforts of the children to help them.

The bus returned to Britain and the children were taken to the reporter’s TV news studio, to compensate for their early departure from Poland. A news bulletin was imminent. An assistant ran in with the first pictures from Poland. The pictures were broadcast. They depicted scenes which the children had witnessed, the beating, a leaflet, all doctored by the Polish state broadcaster to suggest that Solidarity members had instigated the violence.

As these pictures went out in our working mock-up of a news studio, the children invariably objected to the misleading images. The news production team realised their mistake and that they had missed the fact that they had journalistic gold in front of their noses, eye-witnesses to the events who were sitting in their studio. After a furious dressing down from their boss, the production team invited the children to rewrite the martial law item for the next bulletin. Just before their version was broadcast, the action stopped and one of the actors briefly cautioned the children to consider how TV news is constructed and how it can be manipulated.

That was the real thrust of the production. The Polish narrative served it well. It was its suitability for the theme which made us choose it rather than a burning desire to tell this particular Polish story, although I still elicited a kind of half-baked satisfaction at being able to engage with Poland on this limited level.

Aside from this production, I remained distant from Poland for most of my twenties. My parents continued to visit Adam and Aniela and, in 1986, took Uncle Kazik with them from

Glasgow. This was his first and only return to Poland although he had been reunited with Adam long before then. Adam visited Scotland several times from the early ‘60s, bringing with him, in turn, Aniela, Jan the Butcher and Ula.

My father became active in the Scottish-Polish Cultural Association, attending events at the Polish Consulate in Edinburgh and working with an Invergordon Pole, Andrzej Zamrej, and others, to organise the annual remembrance service which took place at the Invergordon Polish War Memorial on the Sunday after Armistice Day. Andrzej also managed to bring a Polish football team to Scotland, where they played the young Alex Ferguson’s St. Mirren and visited Easter Ross.

My interest in Eastern Europe during the ’80s was sustained by three friendships, two of which I made at Bristol University. Ted Braun was my tutor in third year, a fluent Russian speaker who ran courses on British political theatre and Marxist Aesthetics, among others. I also spent some time babysitting his sons, Felix and Joe. Ted had worked in intelligence during his national service. He was an expert on the great Russian theatre director Vsevolod Meyerhold, who was shot during Stalin’s Great Terror of 1937-8. Ted had visited Moscow several times. We often discussed the history and current affairs of Eastern Europe and he took a great interest in my father’s life. They met a couple of times, conversing a little in Russian and my father made him a coat, which Ted still wears.

I also befriended Misha Glenny. Misha was studying German and Drama a year ahead of me. His father was the brilliant translator of Russian, Michael Glenny. Michael’s great love of Russia was reflected in his son’s first name. Misha is an

extraordinary

and celebrated journalist and writer, a passionate, ebullient character and a wonderful linguist. When he finished his degree, he spent a year studying in Czechoslovakia, as it was then. Following the brutal clampdown which destroyed

the Prague Spring, the Czechoslovak government had become perhaps the most oppressive in the Eastern Bloc. Ostensibly, Misha was studying the work of Karel Capek. He wouldn’t have been allowed in if he’d proposed anything which the Czech authorities judged to be controversial or potentially subversive. But during his stay, Misha made contact with and befriended members of Charter 77, the underground Czech resistance movement whose figurehead was the great dramatist and subsequent first president of post-Communist Czechoslovakia, Vaclav Havel. As well as German, Misha learned to speak Czech, Serbo-Croat, Russian and Hungarian. In the mid-80s, he became a stringer for the

Guardian

, basing himself in Vienna, and within a few years, he was the BBC’s Eastern Europe correspondent.

I occasionally met with Misha during his visits to London and Oxford, where his mother lived. He was, and is, always great company, full of energy and passionate commitment to his work. His understanding and analysis of the political

developments

and undercurrents in Eastern Europe were always perceptive and accurate. He was warning his superiors in London of the impending wars in the former Yugoslavia long before they took him seriously, long before they happened. I was somewhat in awe of Misha’s achievements, which were to become even greater in the years after 1989, but I think he welcomed the relief of seeing old friends for the

craic

. I think he also appreciated the fact that I had some understanding of what he was talking about because of my Polish background. We’d chew the fat about what was going on in Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and the rest over beer and whisky and usually move on to singing soul numbers. We even attended an Oxford United match once during their heyday with John Aldridge up front and the corpulent Czech-born media baron Robert Maxwell in the chair.

Tom Morrison was with me at Inverness High School. We

acted together in our school production of ‘The Crucible’ in 1976 and, as I’ve mentioned, spent our first independent summer holiday that year in Bavaria. By 1983, Tom was a graduate in German living in Berlin and working as a

translator

. I visited him there for a week in February 1984. The Wall was still there, of course. Most of my week was spent as a tourist in West Berlin, visiting art galleries and museums and drinking with Tom in his favourite pubs. I sampled West Berlin’s counter-culture, dancing in nightclubs in Kreuzberg, with a mixed clientele of gays and straights, to Velvet Underground, Kraftwerk, Iggy Pop and post-punk German industrial noise and guitar bands such as Einsturzende Neubaten and DAF (Duetsche Amerikanische Freundschaft). Young men were exempt from National Service in West Berlin, I think as a way of maintaining the city’s population, and there were several thousand from other parts of West Germany who lived there to avoid it too. Many of them lived in Kreuzberg, which was full of squats and anarchists. Often, it was these young people who were responsible for the vibrant graffiti which covered large sections of the western side of the Wall.

The East German authorities administered a system of one-day visas for visitors from the West, mainly as a

concession

to Berlin families which had been divided by the city’s partition. The border crossing I used was underground, at a station in the Berlin metro.

Berlin had become the pre-eminent symbol of the Cold War. During the post-war rebuilding of the devastated city centre, the Communists and Capitalists of East and West competed with each other, constructing ostentatious buildings which attempted to show off the virtues of their regimes, taunting each other across the Wall. In the west, Mies van der Rohe’s steel and glass Neue Nationalgalerie; in the East, Dieter and Franke’s Fernsehturm (TV Tower); in the West, Scharoun and

Wisniewski’s Staatsbibliothek and Kammersmusiksaal; in the East, Graffunder and Swora’s Palast der Republik. Each of these buildings asserted cultural and political hegemony and superiority. Aside from the Palast der Republik, which housed the DDR Parliament and numerous cultural events, before being condemned for asbestos contamination and pulled down, they remain as essential parts of the reunited city.

In 1984, one couldn’t escape the fact that they served two opposing ideologies, that they represented the architectural apogees of the two versions of contemporary German society. Alongside the buildings, the centre of East Berlin was decorated with socialist realist murals and slogans, West Berlin with the neon signs of multinational corporations, crowing from the top of its skyscrapers. It all seemed designed to make the individual feel small, insignificant in the face of such powerful organised forces. I certainly did, walking across the grey expanse of Marx Engels Platz and past the monolithic blocks of Karl Marx Allee. It all became more human for me in East Berlin when I visited a department store and bought some cute, kitsch kitchenware which caught my eye.

I watched goose-stepping East German soldiers change the guard at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and was careful to avoid photographing the Soviet Embassy on Unter Den Linden, not wanting to cause a diplomatic incident. There, I was only a few hundred metres from the Wall at the Brandenburg Gate. At one point during my stay, I took a train in the evening which ran alongside the Wall on a raised track for a minute or two. It was dark, and I caught glimpses through the windows of flats on the other side where people were living moments of their domestic lives, eating dinner, reading, watching TV. During these moments, where ordinary people on both sides of the wall were doing exactly the same things, the city’s division seemed so absurd. I flew back to London and my own little flat in a tower block in Bethnal Green,

depressed by the seemingly immovable

status quo

of the Cold War. I didn’t know that the main architect of the Cold War’s demise, Mikhail Gorbachev, would assume power in the Soviet Union within a year.